Gender and Politics: The Road to Women Empowerment

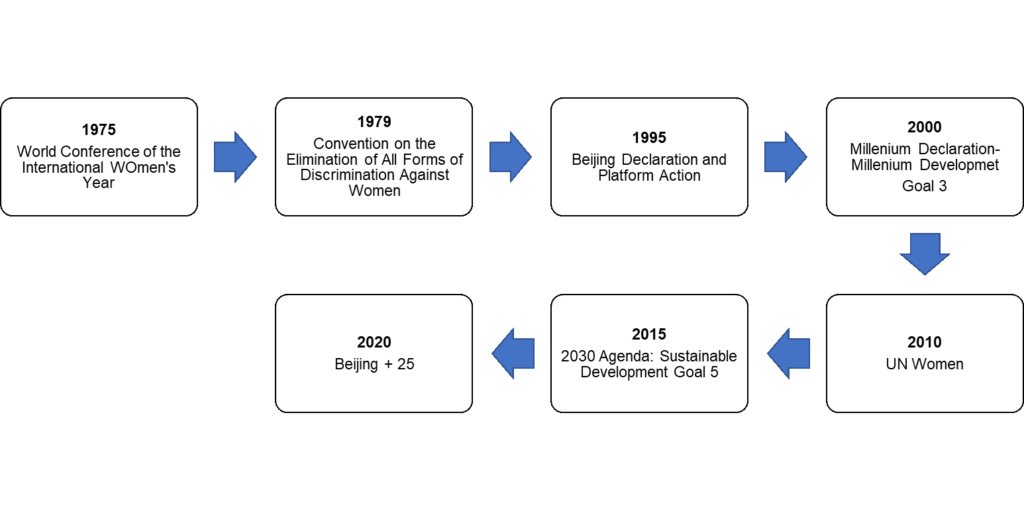

The road to Women Empowerment has been a long and arduous journey. Currently, the agenda to increase women’s participation in political leadership is receiving universal support through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 5.5 which seeks to ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership, and at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life. Women’s representation in political decision-making continues to increase but at a dragging pace, 25 years after the implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action, which remains the world’s most comprehensive agenda for gender equality. The latest World Economic Forum Global Gender Report shows that at our current pace it will take another 100 years for the world to achieve gender-equal political representation. For example, having only one woman for every four men in parliaments around the world is a clear indication of how ineffective societies are at tapping into the potential talent of more than 50% of the population.

The latest World Economic Forum Global Gender Report shows that at our current pace it will take another 100 years for the world to achieve gender-equal political representation. For example, having only one woman for every four men in parliaments around the world is a clear indication of how ineffective societies are at tapping into the potential talent of more than 50% of the population.

The participation of women in politics produces substantial gains for democracy including greater responsiveness to the needs of the citizens, increased cooperation across party and ethnic lines and a more sustainable future. In addition, women’s participation in politics helps promote gender equality and affects both the range of policy issues that get considered and the types of solutions that are proposed (Galston, 2001; Pepera, 2018). Even though (Ballington, 2008) asserts that “the involvement of women in all aspects of political life produces more equitable societies and delivers a stronger and more representative democracy”, studies show that women have been under-represented since the middle of the last century(Paxton et al., 2007; Duverger, 1955; Lovenduski, 1981; Schlozman et al., 1993)

This is because women face a number of barriers when they decide to venture into politics which limits their political participation. While both men and women express concern about the many potential downsides of political campaigning, for women, there is the added worry of stereotypical discrimination (media depiction and voter perceptions of ‘a woman’s place’), the difficulty of fundraising and the loss of privacy.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, due to low education, family resistance, patriarchy and inadequate resource mobilization women face issues of oppression in terms of political exclusion (Tagoe and Abakah, 2015; Jongwilaiwan and Thompson, 2011). Female political representation in Ghana is still insignificant 25 years after the restoration of multi-party democracy in 1992. These barriers can only be removed when more women are represented in politics and are seen as equal representatives to their male counterparts (Koch-Mehrin, 2018).

Female Political Leadership: The Ghanaian Context

Ghana, as a signatory to various regional, continental and international frameworks and has pledged on various forums and platforms its commitment to promoting gender equality and women empowerment by making notable advancements towards female participation and inclusion in the top echelons of political and public sector decision-making.

Despite societal, cultural norms, patriarchal practices and the current socioeconomic status which continues to discourage the participation of women in politics, Ghana has made several efforts to increase the participation of women in governance. Ghana’s first President Dr. Kwame Nkrumah introduced the Representation of People’s Amendment Bill (which made it possible for women to participate in politics), 1992 Constitution (which recognises equal rights of men and women in all spheres of life and prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sex, religion, gender and ethnicity) and Ghana National Gender Policy in 2015 (to mainstream gender equality and women’s empowerment concerns into the national development process) (Republic of Ghana, 1992; Oquaye, 2004). Since then many attempts have made at increasing the number of females in political leadership. These include the appointment of females to key institutions like Chief Justice in 2007, Speaker of Parliament in 2009 and Chair of the Electoral Commission of Ghana in 2015 and 2017. Minority parties have over the years also nominated women as running mates.

Even though females represent about 52% of Ghana’s population, women’s representation and participation in politics does not reflect the exemplary nature of its political status among peers in like Rwanda (51.9%), South Africa (48.6%) and Ethiopia (47.6%) (Musau, 2019).

Currently, women make up 12.7% of parliamentarians, 19.25% of ministerial appointments, 12.36%) politically appointed ambassadors and 17% Municipal and District Chief Executives. Using the UN’s Women Agenda 2030 benchmark (having a female President or Vice President, holding 60 per cent of ministerial positions, 50 per cent of Vice Chancellor and Professorial positions in the universities, and 60 per cent of Chief Executive Positions in state organizations ) to measure the level of progress in bridging the gender gap in women’s representation in decision-making bodies, Ghana’s performance falls short (Dzradosi et al., 2018). Indeed, the Global Gender Gap Report (2020) ranked Ghana 107 out of 153 countries for the gender index on political, 63 years after being the first country in Sub-Saharan Africa to attain independence.

Enter, the nomination of Prof Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang as Running Mate of the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC).

The Nomination of Professor Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang: Context and Perspective

It’s Her! was the reverberating echoes of excitement that emanated from media outlets and Ghanaian social media spaces on July 6, 2020. A former University don had been appointed as running mate to the leader of the largest opposition party in Ghana. ‘History has been made’ many added. The selection of Prof. Opoku-Agyeman as the running mate, is symbolic because this is the first time the idea of Ghana getting a female Vice President looks realistic as none of the two major political parties, (NDC) and New Patriotic Party (NPP) has before appointed a woman to this role, in Ghana’s political history.

In announcing her nomination and subsequent outdooring, former President John Mahama (Flagbearer) described Prof. Opoku-Agyemang as a distinguished scholar, a conscientious public servant and a role model who has contributed to shattering the many glass ceilings that have held women down for generations. Many Ghanaians believe that the nomination of Prof. Opoku-Agyemang brings integrity not only to the NDC ticket but to the larger political discourse from insults to issue-based discussions and policies. Additionally, most Ghanaians believe she exhibits truthfulness and sincerity and commitment, qualities they believe she possess after her sterling years of public service to the country. It therefore comes as no surprise that her announcement has generated such an excitement in Ghana and has been met with a sea of endorsements and congratulatory messages from notable women’s groups such as African Women in Leadership Organization (AWLO), International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA-Ghana), The African Centre for Women in Politics (ACWP).

In her acceptance speech, Prof. Opoku-Agyemang said that what mattered most to her was to hold the door open for those behind and create other avenues for self-actualization for many more. Her mission would be to ensure that the voices and concerns of children, the youth and aged, and persons with disabilities are reflected in critical decisions, by strategizing to solve long-standing problems of needless and unproductive discrimination, and thrive as valued citizens of Ghana.

Born 22 November 1951 in Cape Coast in Ghana, Prof. Opoku-Agyemang holds Masters and Doctorate degrees from York University in Toronto, Canada in 1980 and 1986 respectively. She is the recipient of four honorary doctoral degrees; many national and international awards; she serves on several councils, boards, and committees including UNESCO and has published many books and articles. She is also a two-time Fulbright scholar and is currently a Fellow of the Commonwealth of Learning (COL).

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang was appointed the Vice Chancellor of the University of Cape Coast in 2008, the first female Vice-Chancellor of a public University in Ghana and was later appointed as the Minister of Education in 2013.

Among her stellar achievements as Ghana’s Education Minister, Prof. Opoku-Agyemang reduced teacher absenteeism from 27% to 7%, abolished the quota system at the Colleges of Education which led to enrolment increasing from 9,000 to 15,400, recruited 2,400 mathematics and science teachers as a special intervention to improve the teaching and learning of mathematics and science at the Senior High School level, secured funding from the African Development Bank under the Development of Skills for Industry Project (DSIP) which was utilized for the construction of 13 modern and well equipped Technical Institutes across the country and eliminated the obnoxious shift system in public basic schools.

Another prominent achievement which has stood out recently is her contribution to health care with the establishment of the West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP). During her tenure as Minister of Education that Prof. Opoku-Agyemang led negotiations which secured funding from the World Bank for the establishment of WACCBIP in 2013 in Ghana. In April 2020, WACCBIP announced that it had succeeded in sequencing the genomes of SARS-COV-2, the virus responsible for the coronavirus. This critical data is a major boost to global efforts to find a vaccine for the disease.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the issue of female leadership back into sharp focus. Evidence shows that throughout this outbreak, some countries have done remarkably better than others. These countries have one thing in common: female leaders. Katrín Jakobsdóttir of Iceland, Erna Solberg of Norway, Angela Merkel of Germany and Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand. This places Prof. Opoku-Agyemang in the right company of women leaders who have contributed in shaping the right global response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Globally, research by UN Women estimates that men represent 77% of parliamentarians, 82% of government ministers, 93% of heads of government and 94% of heads of state. Today, one can name all of the current female country leaders in less than 30 seconds. This explains why whenever a woman reaches the top of an organization or political party, it makes global headlines, as seen by coverage by international news such as Reuters and BBC etc following the announcement of Prof Opoku-Agyemang as Running Mate.

Since her nomination, many women groups have issued congratulatory messages and a fan clubs made of mainly women have sprung up all over especially on the Ghanaian social media scene to form a community around the Prof under the global hashtags #ImWithHer and #RepresentationMatters. Surprisingly, these are not only feminist movements whose endorsements are expected but rather your everyday woman. Rasheeda Adams writes on her Facebook post “On 7th January when my President and Vice President-elects are being sworn in and they stand up to take their oaths, I want at least one of them to look like me. I too, want to feel represented. It’s only fair. This is why #ImWithHer”. Many of such women have dedicated their social media spaces push her messages and thereby forming a community akin to the ‘Commanders of the Night Watch’ of Game of Thrones fame to stand up and defend her whenever there is a deliberate attempt to move from a debate of ideas and policies to fight off misogynistic attacks on her person. This has helped in shaping the debate so far from the usual insults to policy and achievements.

A key to political success of female candidates in the past was the display of masculinity. However, in recent times, this is no longer acceptable. Today, the new and effective strategy is a trade-off found between likeability and competence laced with sound policy discourse which she can adopt to endear herself to the Ghanaians especially the women who constitute over 52% of the voting populace.

A lot has been accomplished in the last century and so much more can be accomplished in the years ahead. But there must be a concerted effort to strengthen women’s political participation at all levels to achieve ambitious goals and see true transformative change, because a woman’s place is in politics (Koch-Mehrin, 2018). For now, Ghanaians can bask in this dawn of a new dimension in the female empowerment journey and wish Prof Opoku-Agyemang well.

Adwoa Serwaa Bondzie is an MSc Public Policy student in the Department of Social and Policy Sciences at the University of Bath.

References

Ballington, J., ed., 2008. Equality in politics: a survey of women and men in parliaments. Reports and documents. Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Duverger, M., 1955. The Political Role of Women. (Paris: UNESCO). American Political Science Review, 50(4), p.221.

Dzradosi, C.E., Agyekum, M.W. and Ocloo, P.M., 2018. A Gender Analysis of Political Appointments in Ghana Since Independence. Accra: Institute Of Local Government Studies and Friedrich-Erbert-Stiftung.

Galston, W.A., 2001. Political Knowledge, Political Engagement, and Civic Education. Annual Review of Political Science, 4(1), pp.217–234.

Jongwilaiwan, R. and Thompson, E., 2011. Thai wives in Singapore and transnational patriarchy. Gender Place and Culture - GEND PLACE CULT, 20, pp.1–19.

Koch-Mehrin, S., 2018. Why a woman’s place is in politics. Women Deliver [Online]. Available from: https://womendeliver.org/2018/womans-place-politics/ [Accessed 12 July 2020].

Lovenduski, J., 1981. The Politics of the Second Electorate: Women and Public Participation: Britain, USA, Canada, Australia, France, Spain, West Germany, Italy, Sweden, Finland, Eastern Europe, USSR, Japan [Online]. 1st ed. J. Hills, ed. London: Routledge. Hills/p/book/9781138353633 [Accessed 29 July 2020].

Musau, Z., 2019. African Women in politics: Miles to go before parity is achieved [Online]. Available from: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2019-july-2019/african-women-politics-miles-go-parity-achieved [Accessed 13 July 2020].

Oquaye, M., 2004. Politics in Ghana 1982-1992: Rawlings, Revolution and Populist Democracy. Osu, Accra, Ghana.

Paxton, P., Kunovich, S. and Hughes, M., 2007. Gender in Politics. The Annual Review of Sociology .

Pepera, S., 2018. Why Women in Politics? Women Deliver [Online]. Available from: https://womendeliver.org/2018/why-women-in-politics/ [Accessed 12 July 2020].

Republic of Ghana, 1992. Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. Ghana Publishing Corporation (Print. Division).

Schlozman, L., Burns, N., Verba, S., Schlozman, K.L. and Burns, N., 1993. Gender and the Pathways to Participation: The Role of Resources." Presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

Tagoe, M. and Abakah, E., 2015. Issues of Women’s Political Participation and Decision-Making in Local Governance: Perspectives from the Central Region of Ghana. International Journal of Public Administration, 38, pp.1–10.

Respond