Marcelle McManus is a Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bath.

We have 12 years to limit climate change catastrophe, warns the UN. This is a stark warning to all of us that if we want to ensure continued access to the kind of lifestyles we have, we need to act now. But even with action our lifestyles are under threat. Even limited warming, warns the report, is likely to mean displacement of millions of people due to sea level rise and a decline in global crop yields.

Knowledge of climate change impacts are nothing new. Policies to reduce our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been in place for decades in some countries. Previously, targets were based around a limit of 20C temperature increase, but during and after the Paris Agreement, many countries, particularly Small Island Developing States (SIDS), campaigned for a lower temperature increase target. This was predominantly because these nations are particularly susceptible to climate change and associated sea level rise – some SIDS stated they may disappear if a 1.5°C limit is breached.

The recent IPCC report explores the differing impacts associated with a difference of 1.5 and 2 degrees. The report was commissioned in 2015, meaning it took almost three years to research and write. According to this report we have only four times that to act. Will we do it?

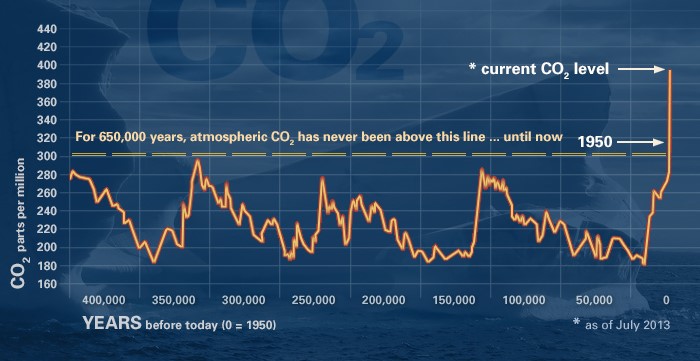

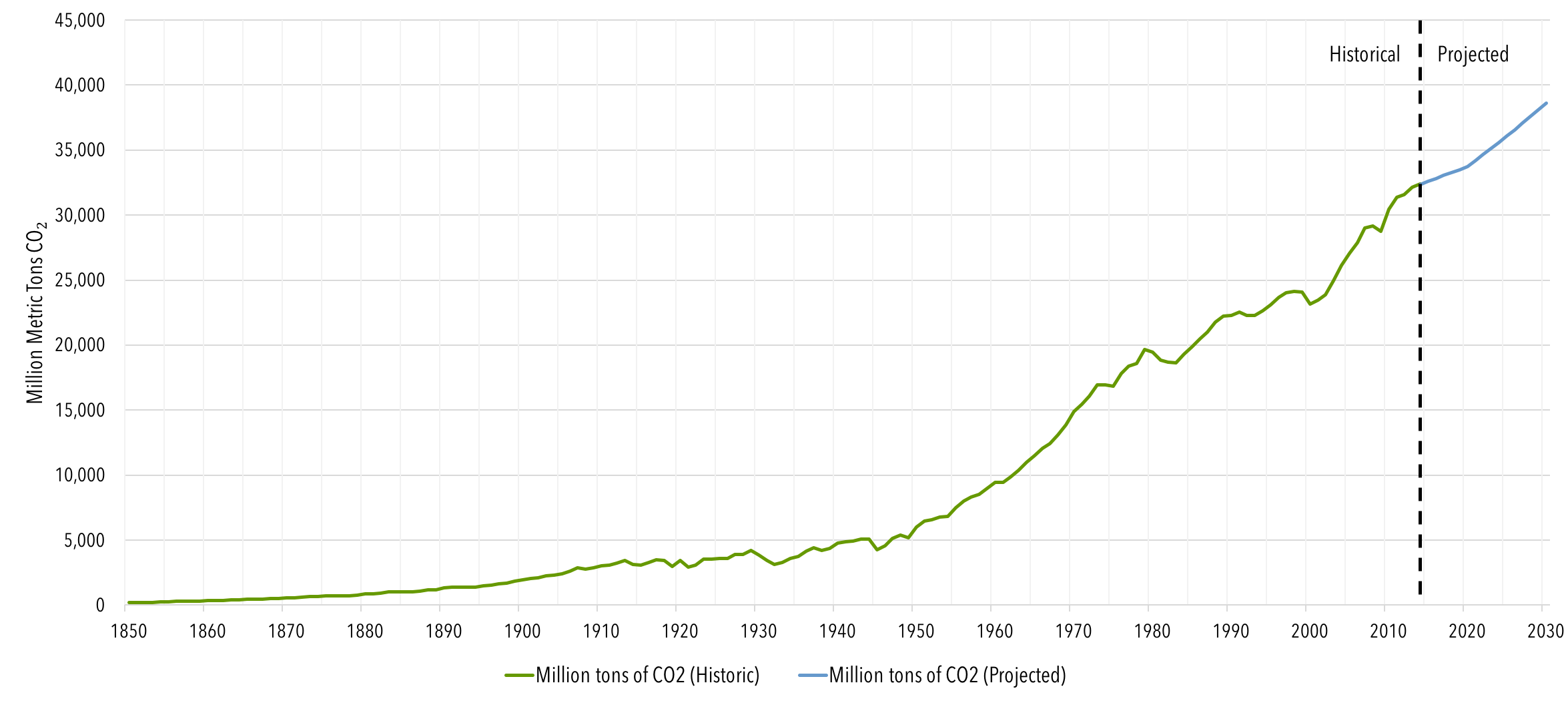

Scientist have warned for decades that rising atmospheric concentrations of GHGs risk affecting the climate, and yet still the emissions rise (see Figure 1 a and b). The latest IPCC report, basically a literature review of thousands of academic and industrial papers and studies, shows that that the difference between allowing the earth’s climate to raise by 2°C and 1.5°C is stark.

A direct impact of this extra increase in temperature is the difference between virtually all the worlds’ coral being wiped out, rather than 70 – 90% of the world’s coral being wiped out. As coral is a carbon sink (i.e. it acts to store carbon), clinging on to even 10-30% of our coral is important. Putting the intrinsic value of carbon aside, even if we only want to keep the coral from a carbon management perspective, a rise in temperature by half a degree will make a big difference. Similarly the increase of 2°C in temperature may also cause sea levels to rise an extra 10cm (wiping out many of those SIDS).

Can we do it? Depending on geography and politics, policymakers have been working towards a 2°C reduction with a mixture of apathy and enthusiasm. Some European Union environment ministers want to adopt 1.5°C as a guide to policy before a UN summit in Poland in December. The Australian government has rejected the IPCCS report’s call to phase out coal by 2050, stating that Australia should absolutely continue to use and exploit its reserves. This is particularly problematic given that according to the research evidence, the 2°C increase would mean the decimation of the Great Barrier Reef.

According to the New Yorker, Donald Trump appeared to have never heard of the IPCC before this report was published. Simultaneously, the US is minimising the impact of GHG reducing policies and rules as part of a string of policy changes to dismantle Obama’s climate legacy plans (including withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and repealing the Clean Power Plan). When justifying rolling away from a required greater vehicle efficiency the administration pointed out that the reduction of six billion tons of CO2 was a drop in the ocean compared with global emissions – so why would they bother?

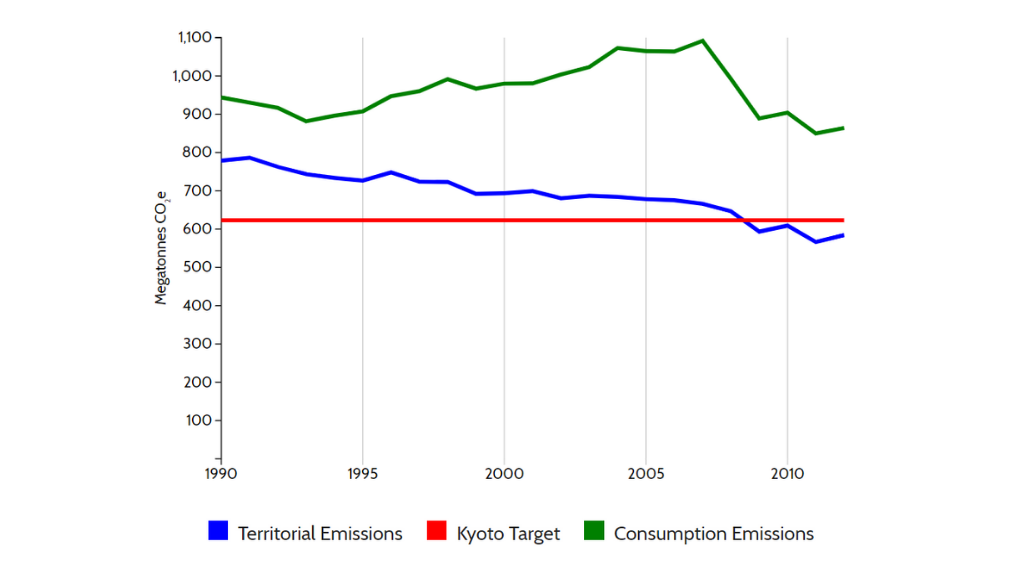

We in the UK are reducing our emissions – so we can lead by example. The UK has developed and signed up to a number of strategies and targets to reduce emissions, most notably the Climate Change Act, which legally obliges an 80% reduction in GHG emissions by 2050. But just because a country is meeting its emission reduction targets doesn’t mean it isn’t responsible for increased emissions elsewhere. The way national targets are measured means that some countries, including the UK, effectively “outsource” their emissions to other regions or countries.

When we calculate our emissions we include those which are emitted here, and in the UK there is a general trend of emission reduction. This is great – but considering this from a wider (systems) perspective, we are also responsible for the emissions produced in the process of providing the goods and services we buy. For example, if I buy a computer, or a solar panel, that is made in China, none of the emissions related to making that product (the emissions from the extraction of the raw materials or the emissions from the factory) are reported in our territorial emissions – they are reported by China. When an increasing number of our products are made elsewhere this makes it unsurprising that our territorial emissions decrease even if our consumption of goods increases. And if we see our reported emission decreasing as a nation we are bound to believe that we’re doing our bit to reduce emissions.

Nevertheless, our global supply chain means that little we use is completely made or produced within the country in which it is purchased. Using a wider systems, or life cycle based approach, this “consumption-based” perspective looks at the whole life cycle of products consumed in a nation. Evidence suggests (Figure 2) that supporting our lifestyles actually causes far more GHG than those just emitted within our national boundaries. Again, this matters because of the global impact. The UK is just as affected by a tonne of GHGs emitted in Beijing as in Birmingham. The world’s GHG emissions don’t respect borders. The people in those low lying island states are just as affected by a tonne of GHGs emitted there as in the US or China; more so due to the increased severity of the impact in those regions. Therefore, unless emissions are addressed, calculated and accounted for on a global scale (or based on consumption), we run the risk of frustrating the purpose of any national strategy by shifting the burden from our shores to others.

This environmental (in)justice is questionable. Our actions have a real and long term impact elsewhere in the world. Often it is, and will continue to be, people with less access to goods and services already that will suffer the most. We need to think carefully about our impact, our emissions now, and about who will be affected. This is not a regional problem. Emissions in any country have a global impact. What our neighbours do (on a large and small scale) makes a difference. Apathy will drive us to either paralysis by analysis or simply running out of time.

With a clear approach we could deliver mechanisms to minimise the catastrophic impact of climate change. But we need to act fast, we need to act globally, and we need to think big. We need to remove arbitrary boundaries around our calculations and take a system wide perspective to dealing with, and reporting emissions, otherwise we will continue to kid ourselves that we are doing okay.

Respond