Nick Pearce is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath.

Can Jeremy Corbyn once again pull off that rare trick in politics, of being a winner in defeat? Yes, say the pundits. The ‘fundamental asymmetry of this election is that while Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister, will be out if he does not claim a clear majority, Labour can lose ground and still put its leader in Downing Street’, writes Robert Shrimsley today in The Financial Times. Having alienated the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the argument goes, Boris Johnson will have no viable partners if he can’t secure a majority. Jeremy Corbyn, on the other hand, can turn to pro-Remain parties to sustain him in a minority government. With echoes of the outcome the last time a general election was held in December in 1923, Johnson would lose office and the baton would pass to the Labour leader to form a minority administration.

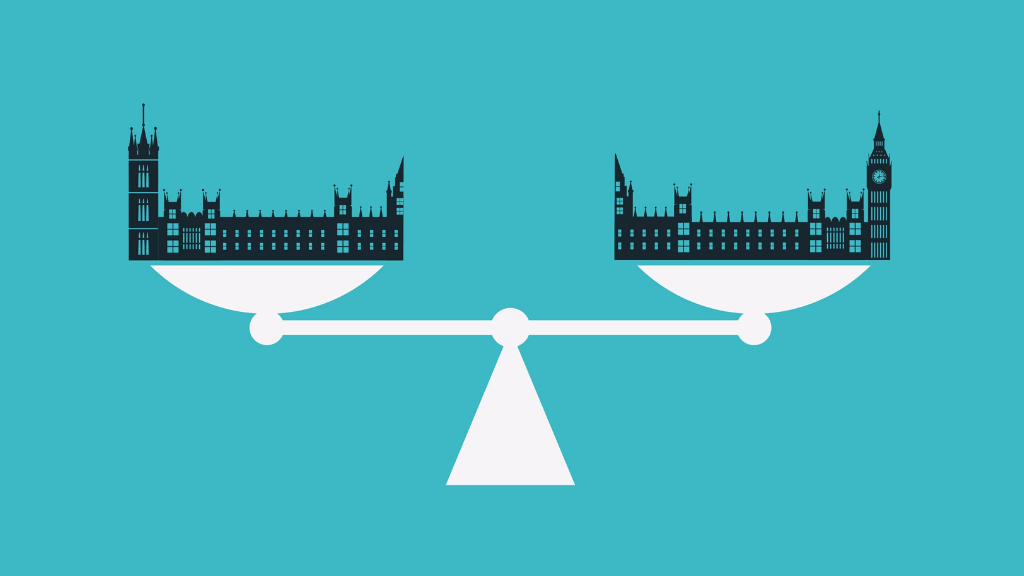

In practice, the politics of a hung parliament will be much more complex and messy than this. Boris Johnson will have the right, as the sitting Prime Minister, to remain in office and try to form a new government, unless the opposition parties can demonstrate that he would be defeated on a confidence vote and an alternative administration could be formed. Absent a written constitution or statute governing the formation of an administration after a general election, the Cabinet Manual – a guide produced by the senior civil service on behalf of the government – stipulates that:

‘Where an election does not result in an overall majority for a single party, the incumbent government remains in office unless and until the Prime Minister tenders his or her resignation and the Government’s resignation to the Sovereign. An incumbent government is entitled to wait until the new Parliament has met to see if it can command the confidence of the House of Commons, but is expected to resign if it becomes clear that it is unlikely to be able to command that confidence and there is a clear alternative.’

It is a matter of some debate whether the sitting Prime Minister has a duty to stay in office until the Queen can appoint a new Prime Minister. The Cabinet Manual rather coyly states that ‘recent examples suggest that previous Prime Ministers have not offered their resignations until there was a situation in which clear advice could be given to the Sovereign on who should be asked to form a government. It remains to be seen whether or not these examples will be regarded in future as having established a constitutional convention.’

Regardless of whether Johnson has a right or duty to stay in office, the asymmetry that he faces in raw politics is reversed in the constitutional conventions. He is the incumbent until the opposition can agree on an alternative. If, as seems likely, the Conservatives win the largest number of seats at the general election by some distance, he will also have political momentum behind his incumbency. This would be the reverse of the situation that faced the parties in 2010, the last time that a hung parliament was anticipated during the election campaign. Before the general election that year, Nick Clegg defied constitutional advice to argue that the party with the ‘biggest mandate’ or ‘the most votes and most seats’ should be given the ‘time and space’ to form a government. He did so precisely to give political legitimacy to the idea that the Conservatives should be given the chance to form a government ahead of the sitting Prime Minister, Gordon Brown. (He did not speculate on what should happen if the party with the most votes did not get the most seats, as in 1951 and February 1974, as his intention was clearly to signal that the Conservatives should form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, rather than Labour).

At the 2010 general election, Labour secured 258 seats. The Conservatives won 306 seats and the Liberal Democrats 57, giving a coalition between the two latter parties a comfortable parliamentary majority. For Labour on the other hand, a viable coalition, or minority government supported with confidence and supply arrangements, would have required not just the Liberal Democrats, but MPs from a clutch of other parties, including in all likelihood, the Democratic Unionist Party. This ‘rainbow coalition’ never looked like a serious prospect.

This is the difficulty that Labour will face again if it cannot significantly improve on its tally of 262 MPs. The big difference this time around is the position of the Scottish National Party (SNP). It won only 6 seats in 2010. It could win between 40 and 50 seats in 2019. That means it will be critical to the formation of any Labour administration. A minority Labour government would need confidence and supply from both the Liberal Democrats and the SNP, and potentially from other pro-Remain parties like Plaid Cymru, the Greens and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) (who may recover some of their representation at Westminster as a result of the pro-Remain electoral pact in Northern Ireland). It will have neither incumbency nor the legitimacy bestowed on the largest party.

Brokering a deal will also take place under the guillotine of the 31 January Brexit deadline. There will be intense pressure to expedite any post-election talks. Yet when Theresa May lost her majority in 2017 and moved quickly to secure the support of the DUP to remain in office, it took her weeks to negotiate a deal. The vote on the Queen’s Speech eventually took place on the 29 June, three weeks after the general election. (By way of comparison, after the 6 December 1923 general election, Ramsay MacDonald’s minority Labour government did not take office until the 22 January 1924).

Under extreme time pressure, and with a complex deal to negotiate, Jeremy Corbyn could choose the path taken (unsuccessfully) by Gordon Brown, and offer to surrender his leadership. More likely, he will seek support for a time-limited government: one that negotiates anew with the EU, seeks a further extension to the Brexit deadline, and holds a second referendum. To guarantee the support of the SNP, he will need to offer a second independence referendum for Scotland, thereby sacrificing the Scottish Labour Party on the altar of an anti-Brexit majority. It is not obvious what price the Liberal Democrats will try to extract, as no Labour Prime Minister will simply revoke Article 50. Even with support from the SNP and Liberal Democrats, any new Brexit referendum could still be derailed by a minority of Labour MPs in a hung parliament.

A minority Labour government will also need supply as well as confidence. The planned November Budget was cancelled and a new government will need to hold one early in 2020. An anti-austerity fiscal programme that enabled significant action on a Green New Deal, increased spending under the Barnett formula to Scotland and Wales, and offered further investment in Northern Ireland, could help glue together support from the pro-Remain parties. But the rest of Labour’s programme – nationalising the main utilities, expanding worker ownership stakes, and so on - will have to be shunted into the sidings.

Given all these hurdles to a Labour minority government, it would not be surprising if Johnson sought a new route to staying in office without a majority. In extremis, he could offer the DUP a No Deal Brexit, renouncing the deal he has reached with the European Union in return for their renewed confidence and supply. There will be fewer One Nation Tory MPs to block his path to No Deal in the next Parliament, although the consequences of such a choice would likely to be devastating for both party and country. At the other extreme, he could risk a split in his own ranks by accepting a confirmatory referendum on his Brexit legislation. That might be enough to secure temporary support from pro-Remain MPs. Each seems implausible until you consider the fraught circumstances of forming a government before Christmas, with a little over a month to go before the Brexit deadline.

Such speculation is all idle if the Conservatives win a decent majority. But if they don’t, we should not assume that it will be easier for Jeremy Corbyn to enter No10 than for Boris Johnson to stay there.

Respond