Dr Rosemary Hiscock is a Research Associate from the Tobacco Control Research Group (TCRG) in the Department for Health, University of Bath. Dr Rob Branston is a Senior Lecturer from the School of Management. Professor Anna Gilmore is Director of TCRG.

Background

On 20 May 2016, the UK (with France) became the second country in the world to introduce plain packaging for cigarettes and rolling tobacco. This meant that tobacco companies could no longer put brand logos, colours or promotional text on packs.

These were replaced with the name of the manufacturer and the product in a standard size and typeface on a ‘drab olive-green’ pack. The packs also had to carry graphic health warnings, front and back and minimum pack sizes were introduced (20 cigarettes or 30g rolling tobacco).

In the year following the introduction of plain packs, tobacco companies were allowed to sell off any traditional packs they had in stock but all the new packs they produced during the 12-month transition period had to conform to the new packaging rules.

TCRG’s previous work had illustrated to government that tobacco companies were continuing to sell cheap tobacco smoked by socioeconomically disadvantaged and young people despite rising taxes. In May 2017, when all packs sold had to be plain, the government introduced a Minimum Excise Tax (MET) on cigarettes. This meant that each pack of cigarettes accrued a minimum amount of tax in order to discourage manufacturers from selling packs at cheap prices.

Analysis

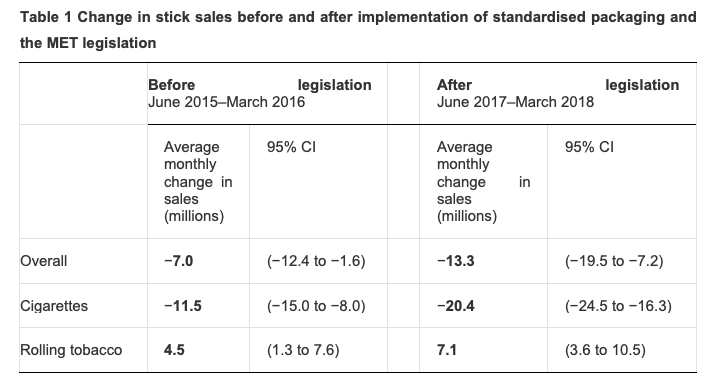

First, we analysed cigarettes and rolling tobacco sales data to understand the impact of the plain packaging law and the MET on prices and quantities sold, and on the amount of revenue the tobacco industry received.

Second, we looked at literature from the tobacco industry, retailers, and industry analysts to understand how the tobacco industry responded to plain packaging.

Findings

On the first, we found that once the new legislation was in place, the rate of decline of tobacco sales almost doubled (table 1), and revenue to the industry fell.

Overall, the tobacco industry kept prices down during the transition but when the new legislation was fully in place, prices grew after a tax rise. However, prices of the cheapest cigarettes rose earlier, around the time the MET was introduced. At the same time, sales of the cheapest cigarettes stopped growing.

On the second, we found that tobacco companies only phased out most colourfully branded products in the last few weeks of the transition period. Instead they used the time to advise retailers about products and packaging that were exempt from the legislation – including cigars, pipe tobacco, and filters – and to produce and push produce cheaper products. Communication between retailers and smokers was viewed as key to making the change smooth to reduce the likelihood of smokers considering quitting.

The legislation also required the removal of brand names that could imply that a product was less harmful so tobacco companies also used the extension to May 2017 to gradually change names. Names previously associated with low-tar cigarettes (e.g. ‘smooth’) were often systematically changed to colour names like ‘blue’, and/or descriptive terms like ‘bright’ and ‘sky’ that are typically associated with the outdoors and a healthy lifestyle. These new names have the potential to continue to mislead smokers that some tobacco products are less harmful.

Research conclusively shows that ‘low tar’, ‘smooth’, ‘mild’ or ‘light’ cigarettes are no less harmful than their full-strength counterparts, despite what smokers might think.

Tobacco companies also used the 12-month transition period to keep their traditional packs on display for as long as possible. In fact, they offered financial incentives to retailers to buy large volumes of old packs last minute and offered to buy back any no longer legal stock.

In short, the transition period was not used as intended: instead, the industry used the extra time to keep selling eye catching branded packs and introduce new products gradually to make the change less abrupt.

Tobacco companies were given a further three years to May 2020 to phase out menthol cigarettes. Again, menthol products continued to be sold until the ban and new products such as mentholated accessories sold separately from tobacco products and ten packs of cigarillos with menthol capsules, not covered by the legislation, were introduced.

What all this means

The tobacco industry claimed that plain packaging would lead to reduced prices and that this would be counterproductive for public health. These claims have been proved false. Plain packaging combined with a MET had the intended effect of reducing sales of cigarettes. It also had the impact of reducing industry profits which explains the real reason for the industry’s opposition to this legislation – it works.

Plain packaging combined with a MET that is increased regularly will likely contribute to further declines in smoking in the UK.

Five key recommendations for other countries planning to introduce plain packs

- Implement plain packaging in combination with a robust tobacco tax system.

- Close all legislative loopholes, including applying plain packaging to all tobacco products and accessories – for example, cigarillos, cigars, pipe tobacco and filter papers.

- Restrict brands to one variant and ban new brands.

- Introduce plain packs very quickly after legislation with no or only a very short transition period in order to:

a) remove branding quickly and reduce tobacco sales as soon as possible,

b) prevent tobacco companies from creating new products and notifying consumers about changes to product names. - Reject misleading tobacco industry arguments.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Are you a decision-maker in government, industry or the third sector? Apply now to our virtual Policy Fellowship Programme for access to University of Bath research and expertise. Learn more.

Respond