Dr Matt Dickson is Reader in Public Policy at the Institute for Policy Research (IPR), University of Bath.

Our latest report for the Department for Education has just been released, showing how undertaking a postgraduate degree impacts upon earnings and employment outcomes at age 35, compared with not continuing in education beyond the undergraduate level.

With employment opportunities receding rapidly in the post-pandemic labour market, postgraduate study is a more attractive option for many students. This report provides timely information for students looking to enhance their prospects in the labour market.

The headline finding is that, on average, graduates of masters degrees do not see substantial increases in their earnings over and above what we would have expected them to earn had they only attained an undergraduate degree.

Women with PhDs boost their earnings by a fair amount, but for men the return on a PhD is negative. However, as we will see, there is much more to the findings than just the average earnings returns, and positive labour market outcomes are to be found for each of the main postgraduate routes.

Looking at raw earnings, we see that masters and PhD degree holders do, on average, earn more at age 35 than those with just undergraduate degrees. For men, earnings are £55,800 (masters), £51,900 (PhD) v £50,800 (undergraduate); with the equivalents for women at £35,400 (masters), £36,000 (PhD) v £32,500 (undergraduate). However, these premia can almost all be explained by the graduates’ background and prior university attainment.

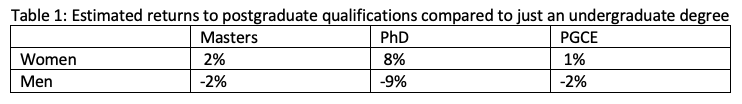

Compared to individuals from similar backgrounds and with the same attainment at undergraduate level, the returns are generally small and, for men at least, negative - as Table 1 shows:

The story is somewhat the reverse for teacher training degrees. In raw terms, at age 35 PGCE graduates actually earn less on average than those with just an undergraduate degree. This is massively so for men, with average PGCE earnings of £38,100 compared to £50,800 for the average undergraduate. It’s also true for women (£28,800 compared to £32,500), but again much of this difference is explained by background and prior attainment. In particular, many of those who choose to do a PGCE are from undergraduate degree subjects that have lower earning potential. When we compare PGCE graduates to undergraduates with similar backgrounds, and who had the same attainment from a similar course at undergraduate level, the returns are still marginally negative for men, but are now a small positive for women.

As we show below, the average earnings returns mask a great deal of variation depending on the subject of the postgraduate degree and the subject of the undergraduate degree. But before looking into that, it is also worth noting that while for men average earnings returns for a PhD look unappealing, having a PhD does reduce earnings variation and so provides some insurance against low earnings. In other words, very few of these graduates ending up with low or no earnings.

Similarly, PGCEs represent a relatively ‘safe’ choice for both women and men. They reduce the chances of not being in employment, and reduce the chance of earning less than £30k, albeit they also decrease the probability of earning more than £40k at age 35.

For women the same is true of masters degrees, although average returns are modest. Compared to an undergraduate degree, having a masters increases employment probability, and increases likelihood of earning more than £30k. It’s important to remember that forward-looking students care not only about earnings levels but also employment security and earnings risk – and this is especially likely to be the case at the moment. Aside from masters for men, all of these postgraduate degrees deliver in terms of insuring against bad labour market outcomes.

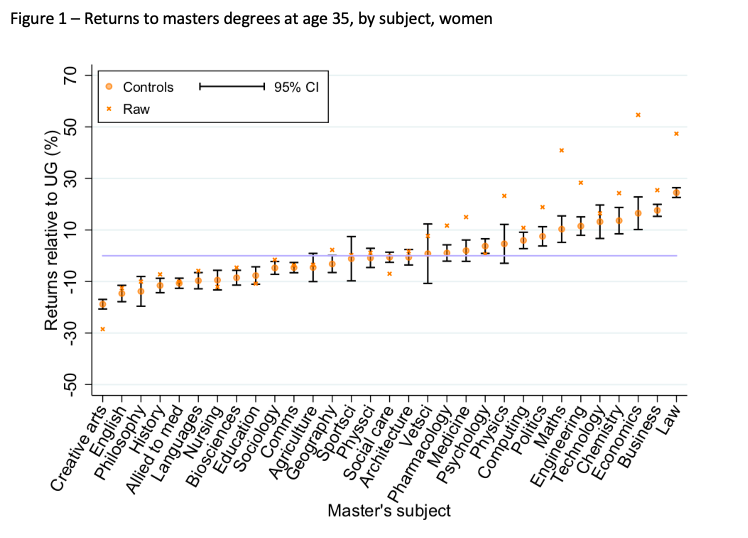

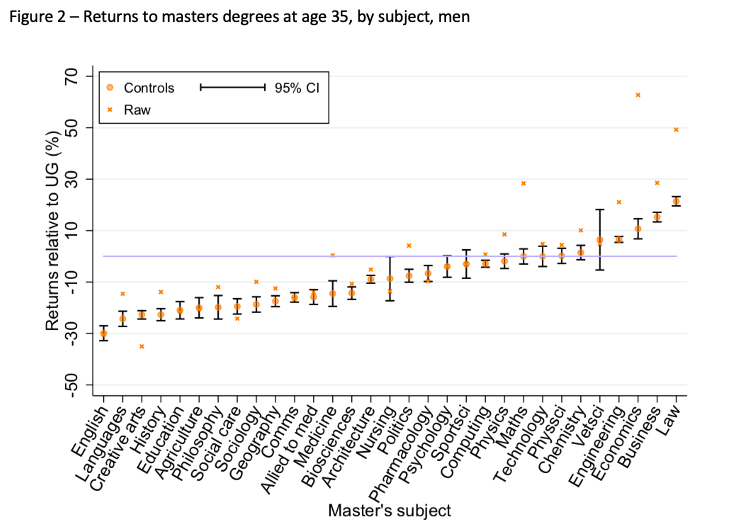

Digging deeper, and focusing on the masters degrees, there is a lot of variation in returns depending on the subject and by prior undergraduate degree subject too, as this latter factor plays a large part in determining how much individuals could earn if they chose not to progress beyond undergraduate level.

As can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, there are large raw earnings premia for many subjects for both men and women, however controlling for background and prior attainment reduces these substantially in most cases. For women there are nine subjects boasting sizeable statistically significant returns, from 6% for computing, up to 17%-18% for economics and business and 25% for law. For the other subjects it is a mixture of zero or slightly negative returns.

For men the number of masters with substantial positive returns is smaller and the number with non-trivial negative returns is larger, with arts and humanities subjects having particularly negative outcomes. At the same time, law, economics and management subjects give double digit returns, law being the highest at a 21% return.

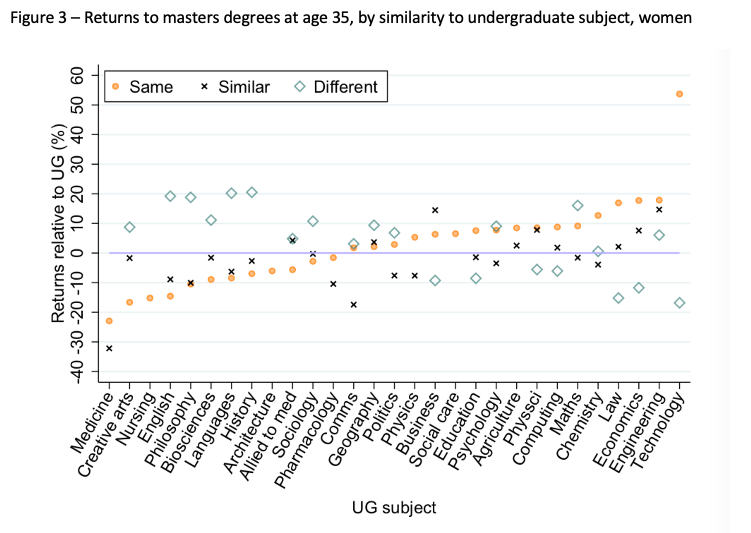

Taking this one stage further to look at difference in returns to doing a masters depending on the undergraduate degree subject, we start to see the importance of the alternative earnings available in determining returns to masters degrees.

For women, subjects like law, economics and business, and some STEM courses, have high returns to an undergraduate degree. We can see from Figure 3 that for students who studied these subjects at undergraduate level, their highest returning masters option is to continue in that same subject. Changing to study a different but related subject reduces returns, and switching to something completely unrelated will likely result in much lower if not negative returns compared to entering the labour market after one of these high returns undergraduate degrees.

At the other end of the chart the story is reversed. For those who chose relatively low returns undergraduate degrees – many arts and humanities subjects – doubling down with a masters in the same subject is associated with large earnings penalties, much below what even their undergraduate earnings might have been. However, switching to a completely different subject for a masters is likely to result in a double digit return over what they would have earned with just the undergraduate degree.

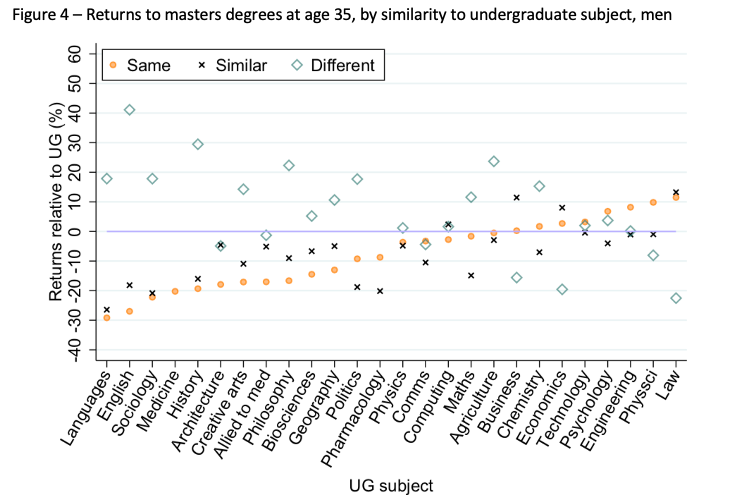

This story is repeated for men. For undergraduate subjects that have high earnings returns – economics, business, law, engineering for example – continuing to masters level increases earnings even further above these high levels, while switching away from them completely for a masters will lead to much lower earnings than would have been available with just the undergraduate degree. Again, conversely at the bottom, doubling down on a low returning undergraduate degree by progressing to masters level will likely be rewarded with a large earnings penalty but switching to a masters in a different faculty is associated with 20%+ higher earnings than would be expected.

These findings in Figures 3 and 4 are really important as they highlight the possibilities for high returning masters degrees for both men and women regardless of undergraduate subject. For those students with arts and humanities degrees considering remaining in higher education to ride out the immediate post-pandemic labour market storm, there are subjects – likely to be found in social sciences – that they could access and reap high returns from. Students are now armed with the knowledge of the importance of subject choice at masters level, given their undergraduate degree, which should help in their decision-making.

It is important however to return to the earlier point. Students, like others, care about employment and earnings stability as well as earnings levels, and almost all of the postgraduate routes analysed in the report provide a degree of insurance against poor labour market outcomes - even PhDs for men, which do not have high average returns.

Moreover, the usual caveats to this sort of analysis apply. For example, we can only estimate the private returns to postgraduate study – there will be wider economic and social returns that we do not capture here. With PhD study for example, we have seen first-hand in the post-COVID race to create a vaccine the importance of leading-edge research undertaken at our HEIs.

This highlights another important consideration: though we have a very rich dataset that allows us to control for many of the differences between those that do and do not take postgraduate courses, there may still be unobservable differences between individuals that we cannot control for. These include differences in motivation or preferences over occupations or working hours. Those motivated to pursue a PhD are unlikely to be doing so for financial returns, but because of a desire to research their subject at the frontier and make a difference in the world.

At this time when young people in particular are bearing the brunt of the economic fallout from the pandemic, many will be considering further postgraduate study. This report therefore provides very timely and critical information, highlighting a number of dimensions of returns to a postgraduate degree beyond just average earnings, allowing more informed choice, all of which should be to the benefit of the students themselves, the taxpayer and wider society.

This blog is based on a new report from the Department for Education, co-authored by Dr Matt Dickson, Jack Britton, Professor Franz Buscha, Laura van der Erve, Professor Anna Vignoles, Professor Ian Walker, Ben Waltmann and Yu Zhu. Read the full report here.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

What a profoundly depressing article in which I detect Gove's malign and corrosive influence. Here the fruits of education, learning and scholarship reduced to their 'return' in the labour market. It demonstrates beyond doubt that modern academic study knows the cost of everything and the value of nothing.