Eun Jung Kim is Researcher at the Asian Demographic Research Institute, Shanghai University. Susan L. Parish is Dean at Bouve College of Health Sciences. Tina Skinner is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social and Policy Sciences at the University of Bath.

In 2018, approximately 14 million individuals, or one in five, had a disability in the United Kingdom. Among them, 7.6 million (23% of the general population) were disabled women and 6.3 million (19%) were disabled men. Disabled women are more economically marginalized than disabled men or nondisabled women based on both their gender and disability. However, little is known about the significance and magnitude of this double discrimination.

Over the last few years, the government has proposed a series of cuts to disability benefits, including the 2012 Welfare Reform Act, which replaced the Disability Living Allowance with the Personal Independence Payment. Stringent eligibility criteria were implemented, and an estimated 47% of people formerly receiving Disability Living Allowance lost or received reduced benefits under the Personal Independence Payment. Disabled women compromised a slight majority of Disability Living Allowance claimants, and thus, the risk of change is likely to impact them more than disabled men.

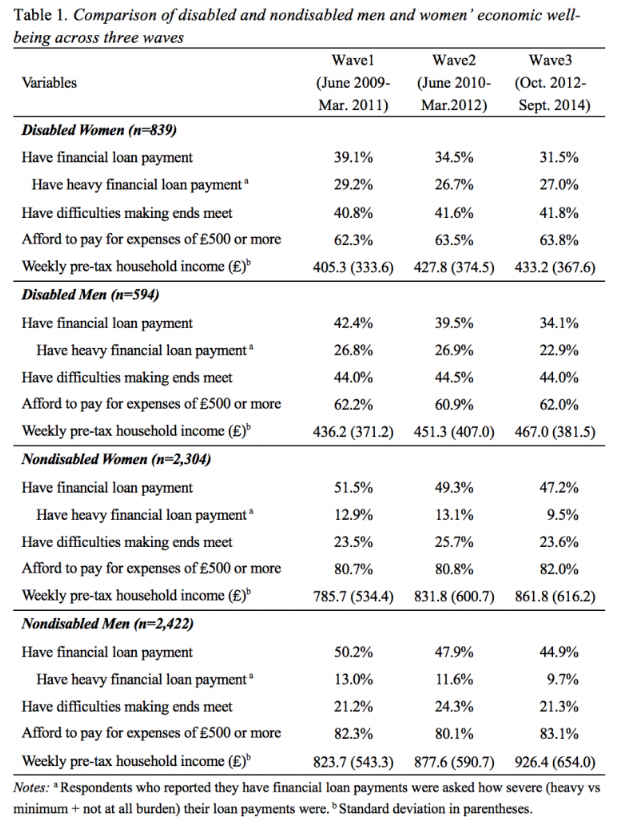

In 2017 the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities raised concerns about the “lack of measures and available data concerning the impact of multiple and intersectional discrimination against women and girls with disabilities.” In our recent analysis, we followed the economic well-being of disabled women between 2009 and 2014 and how they fared compared with disabled men and nondisabled men and women amid the changes (see Table 1).

We found that disabled women were overall more economically marginalized ; however, what was alarming was that the disparity between disabled women and the rest of the groups was also widening. For example, in wave 1 (June 2009 – March 2011) disabled men, nondisabled women, and nondisabled men all had higher pre-tax household income than disabled women: 7% higher in the case of disabled men, 94% higher for nondisabled women, and 103% higher for nondisabled men. In wave 3 (October 2012 – September 2014), the differences increased to 8%, 99%, and 114%.

Also, although the proportion of disabled women reporting heavy financial loans fell slightly from 29% in wave 1 to 27% in wave 3, the differences between disabled women and the rest of the groups actually widened. Our results report that in wave 1 the probability of disabled women reporting their financial loans was heavy was 2 percentage points higher than disabled men and 16 percentage points higher than nondisabled men and women; however, these differences increased to 4 percentage points, 18 percentage points, and 17 percentage points in wave 3, respectively.

Further, we discovered that although very meager, more disabled women reported difficulties making ends meet and the disparities between disabled women and nondisabled women and men widened between wave 1 and wave 3.

Our multivariate analysis showed that even after adjusting for factors such as education, marital status, age, employment status, and family structure, disabled women were significantly worse off than the other groups. This suggests that disabled women with very similar demographic backgrounds to, for example, nondisabled women will nonetheless experience more economic hardship than their nondisabled counterparts.

However, the difference between disabled women and disabled men was not statistically significant, implying that gender difference within the disabled population disappeared once other demographic factors were taken into account. In addition, we discovered that the increasing economic gaps between disabled women and the rest of the groups were no longer statistically significant after adjusting for other demographic factors. This result indicates that the increasing gaps between disabled women and rest of the groups may be due to the increasing differences in our control variables such as employment status, which had significant moderating effects. In fact, in our study, we discovered that disabled women’s employment participation rate dropped the most among the four groups between wave 1 and wave 3, which is itself concerning and may have contributed to the increased economic gaps between disabled women and rest of the groups.

In sum, recent government disability policy cuts and changes have been criticised for exacerbating the economic hardship of disabled people. What our study found was that in addition to the increased economic hardship, the economic disparity between disabled women and the rest of the population widened amid the welfare reform. The evidence shows that the disparity between disabled women and disabled men and nondisabled men and women intensified between 2009 and 2014. Even in areas where economic well-being (i.e. household income, heavy financial loan payments, afford to pay for necessary but unexpected expenses) improved for disabled women between wave 1 and wave 3, the gaps between disabled women and rest of the groups increased.

As a result, in longitudinal studies or government assessments, it is important to not only examine the changes in the target population but also compare populations to have an accurate estimation of their performance. In addition, our multivariate analysis suggests that the increase in the difference between disabled women and other groups was driven by the change in characteristics of the disabled women in particular with regard to their employment.

As such, it is also important to take into account changes in characteristics and labour market status that may be driving the raw results. Disabled women in employment may not have seen their economic position worsen with respect to the other groups but if policy changes led to reductions in their employment rate, the economic position of these women overall will deteriorate. We therefore suggest that government policies should adopt a more intersectional approach, which understands the elevated marginalization experienced by disabled women: the intricate links between disability, gender, and poverty should be considered in policymaking.

In conclusion, our work provides detailed analysis of available data to address the CRPD’s concerns about lack of information about the double discrimination faced by disabled women. Based on this evidence we call for policy intervention to stop disproportionate discrimination faced by disabled women, as well as further work and data collection in this field to monitor future interventions.

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Social Policy & Administration.

This blog was originally posted via British Politics and Policy on 10 April 2019.

Respond