Olli Kangas is a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Policy Research (IPR), Director of Equal Society research programme at the Academy of Finland, and Professor of Practice at the Department of Social Research, University of Turku.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made”, begins St. John’s gospel.

Odysseus fooled Polyphemus by not telling the Cyclops his real name. “My name is ‘nobody,’” said the Ithacan. In vain, Polyphemus shouted for help from the other Cyclopes, yelling that ‘Nobody’ was trying to kill him. The other Cyclopes thought that Polyphemus had gone mad and told him to pray. Polyphemus was powerless until Odysseus was fool enough to reveal his real name. It was only with the name – once Polyphemus had the word – that he could bring a curse upon the Ithacan.

Not only in the Bible, nor in antiquity, do words change the world. Words create images of reality, and images are always true in the sense that they form the basis of our choices and actions.

“Politics is the art of the possible,” claimed Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898). And rhetoric is an instrument of that art. In antiquity, rhetoric was a matter of political persuasion – convincing the people in the agora to support one’s position. What mattered was the credibility of a speech, not necessarily its veracity. Indeed, in politics, things are what they seem. Words create reality. Therefore, those who can define the words and concepts used in political discourse have the power[i].

Words as a creative force in policy reform

In this blog, I will highlight how easily we can manipulate opinions and how presenting a measure in a different frame can affect its popularity. As a concrete example, I use the plans to change the pensioners' housing allowance system in Finland, which have been the subject of much political debate.

In Finland, pensioners have their own housing allowance scheme, which is more generous than the general housing allowance system. A pensioner who has the same income and the same housing costs as an unemployed person may receive substantially greater subsidies. To reduce the rapidly increasing spending on housing, Juha Sipilä’s centre-right government (2015-2019) tried to merge the two systems into one programme. Pensioners were to be covered by the general housing allowance scheme, which would have brought savings both in the benefits and in the administration.

However, the government lost the battle, primarily because the left-green opposition and pensioner organisations were more skilful in using words and framing the issue. Whereas the government justified the reform in overly technical terms as a cost containment measure, the harmonising of two different housing benefit systems and a simplification of the bureaucracy, the opponents of the reform depicted it as the abolition of the pensioners’ scheme and as an unfair measure to implement savings at the cost of the old and frail.

When speaking about the possible reductions in pensions caused by the reform, the government referred to monthly reductions while the opposition constantly spoke about annual losses. The bureaucratic policy frame used by the government was rhetorically much less effective than the moral frame used by the opponents. And as it turns out, arguments referring to morality and social justice are much more persuasive than references to the balancing of the state budget.

Of course, the government could have also asked the rhetorical question whether a poor pensioner is poorer and needier than an unemployed person or a family with children on the same income level and with the same housing costs. A pensioner can get thousands of euros more per year than a low-income household in a very similar situation. Therefore, the integration of the two housing allowance systems should be a matter of creating equality and justice in the treatment of different sections of the population. Here too, a moral framework should be included. However, for some reason, the government did not make use of their most effective and the most persuasive weapons.

The forest will answer in the same way that one shouts at it

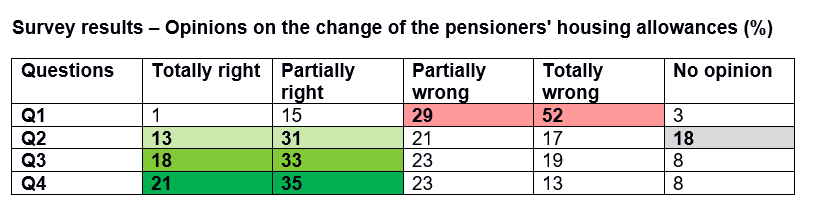

I will illustrate the impact of the above-mentioned rhetorical frameworks by presenting results from an opinion poll I conducted in late 2015. In the survey, a possible change in pensioners' housing allowance was presented in four different ways using different frames as follows:

- Q1: Is it right for the government to cut pensioners' housing allowances?

- Q2: Is it right for the pensioners’ housing allowance system to be merged with the general housing allowance scheme?

The latter option also included two explanatory frameworks:

- Q3: Pensioners' housing allowances are more generous than the general housing allowances. Is it right for the pensioners’ housing allowance system to be merged with the general housing allowance scheme?

- Q4: Pensioners' housing allowances are more generous than the general housing allowances. In some cases, a pensioner can receive hundreds of euros more than e.g. an unemployed person with the same level of income would receive. Is it right for the pensioners’ housing allowance system to be merged with the general housing allowance scheme?

The respondents were given five possible responses: 1) Totally right, 2) Partially right, 3) Partially wrong, 4) Totally wrong and 5) No opinion.

The sample was drawn randomly from the Population Register Centre of Finland. The interviews were conducted by telephone by the market research company Taloustutkimus. The questions were each posed to 505 respondents with similar backgrounds, so that one group of respondents only answered one question. Thus, 505 people responded to the first question, 505 to the second one, etc. The total sample size was 2,020 respondents. The margin of error of the survey is ± 4%.

The power of the word is clear when we take a look at the distribution of opinions in the table. In the first question (Q1), a resounding majority (81%) of the respondents considered the cuts to be wrong and as many as many as 52% considered the policy measure to be totally wrong. The ‘cut frame’ produces strong opinions and strong confidence in opinions. Only 3% could not express their opinion on the issue.

The situation changes substantially when the question addresses the harmonisation of the two benefits schemes (Q2). Interestingly, the share of ‘no opinion’ responses dramatically increases. Almost one fifth of the respondents could no longer express their opinion. At the same time, the opinions turned in favour of the 'harmonisation'. There were now more respondents in favour or the policy option than against it (44% vs. 38%). And this support for the 'harmonisation' increases further when more specific information is provided (Q3 and Q4). Here, the majority of respondents were ready to 'harmonise' the systems. With the fourth framing, almost 60% accepted the measure.

Different political parties, different impacts

There were substantial differences in how the framing influenced the voters of the various political parties. Not surprisingly, the opinions follow the divide between the government and the opposition. In the first question, which framed the issue as cutting pensioners’ housing allowances, 56% of those who voted for the Prime Minister’s Centre Party, 77% of the Conservative Party voters and 77% of the True Finns regarded the government's plan to be partially or totally wrong. Interestingly, a majority of those who voted for the government parties were against the reform, even though it was being pushed by the parties for which they had voted.

As one might expect, the sense of injustice among the opposition party voters was much stronger. 91% of the voters for the Left Alliance and the Social Democrats, and 87% of the Green Party voters, expressed a negative attitude in the first question.

The fourth question, which framed this issue as a matter of treating the different segments of the population equally, also revealed differences of opinion between the voters of the various parties. Here, only 24% of the Conservative voters, 14% of the Centre Party voters and 42% of the Basic Finns considered the 'harmonisation' of the benefits to be wrong. A small majority of left-wing voters (51% of the Social Democrats and 55% of the Left Alliance voters) still considered the 'harmonisation' to be wrong. The Green Party voters had a less negative attitude toward merging the schemes: only 34% of them felt that the measure was wrong.

If the fourth frame had referred to a family with children instead of to the unemployed, the effect of the frame would have most likely been even stronger – like the elderly, children are considered to be ‘good poor’ people, who we want to help and care for.

The moral frame generates strong opinions

Interestingly, as more information is provided, the share of ‘no opinion' answers increases. Question 2 provides non-specific information that is not bound to any moral framework. The result is an increase in uncertainty. This situation is familiar from previous studies that have analysed the efficacy of moral framing[ii]. It also brings to mind Leon Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance, a psychological stress that is triggered by new and contradictory information, in which there are contradictions between a person’s intelligence, their sense of morality and their attitudes[iii]. Whereas in some cases adding information will diminish the level of ignorance, in other cases more information will increase people’s insecurity and lead to cognitive dissonance

We can easily condemn something – e.g. child labour – as being morally wrong, but if more information is added – e.g. that the working children are saving their families from starvation or debt bondage and that they are safe from human trafficking – the certainty in our opinion usually evaporates. Using a strong moral framing, it is easy to simplify an issue into black and white positions, and thus to give definite and strong answers. This is also the basis of political populism: it provides easy moral solutions for very difficult problems.

What do we learn?

A few lessons can be drawn from the above examples. First, words have a divine power to create reality. True is what is considered to be true. By framing an issue one way or another, one can get people to either strongly oppose or support the very same policy measure. Indeed, ‘the forest will answer in the same way that one shouts at it’, as the Finnish proverb states.

Second, the examples above give us some insight into how both opposition and government spin-doctors work. If the opposition parties want to reject the government’s policy initiative, they should always use a strong moral frame when discussing that issue. This is efficient, effective and difficult to challenge. Challenging such a moral frame requires lot of explaining, and in political parlance, those who are compelled to explain tend to lose against those who proclaim a simple political ‘truth’.

Needless to say, the government could use the same tools. However, in times of austerity, cost containment is more difficult to defend morally than to oppose. Of course, the Finnish centre-right government could have emphasised the equal treatment of citizens, the fragmented social security system and the high bureaucratic expenses that result in less money for other more important objects such as child benefits. In this way, the government could have used its own rhetorical arsenal to combat the moral framing of the opposition. And even if these verbal weapons had not been entirely successful, they would at least have sown some seeds of cognitive dissonance. Politics is the art of opportunity, and rhetoric is its tool.

The third and final lesson relates back to the Ancient Greek drama. If Odysseus had not revealed to Polyphemus that he was Odysseus, the son of Laertes from Ithaca, Polyphemus would have continued to believe that it was ‘nobody’ who had caused him pain. But as soon as the Cyclops knew the word, he was able to ask his father, Poseidon, to cast a curse on Odysseus. If Odysseus had acted wisely and not revealed his name, he would have reached his beloved Penelope and his dear son Telemachus much earlier. But then this entertaining adventure story would have been much shorter, and the drama would have remained incomplete.

[i] see e.g., Spector, J. & Kitsuse, M. (1977): Constructing social problems; Goffman, E. (1986): Frame analysis; Bourdieu, P. (2000): Pascalian meditations; Fairclough, N. (2001): Language and Power; Lukes, S. (2005): Power and the Battle for Hearts and Minds; Lakoff; G. (2014): The All New Don't Think of an Elephant!: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate.

[ii] Kangas, O., Niemelä, M. & Varjonen, S. (2014): ”When and why do ideas matter?” European Political Science Review, Vol. 6: (1): 73-92.

[iii] Festinger, L. (1957): A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

Respond