Tony Walter is Emeritus Professor of Death Studies at the University of Bath. His most recent books are Death in the Modern World (Sage, 2020) and What Death Means Now (Policy Press, 2017).

For at least ten thousand years, dying usually meant dying of an infectious disease. But by the start of the current millennium, across most of the world, infections had been effectively controlled through improved living standards, immunisation, and public health measures such as sewers and clean water. Most people now die of the diseases of later life – non-communicable diseases like cancer, heart disease, stroke and dementia. This has transformed what dying means, how it is managed, and what counts as a ‘good’ death.

The old medieval ars moriendi or art of dying, premised on speedy death from infectious disease, has been replaced by modern palliative care’s ‘craft of slow dying’, pioneered first in hospices and now spreading to hospitals and care homes. But this doesn’t fit COVID-19’s return to a world of infectious dying. Reviving medieval deathbed rites is hardly an option, so – if the world is to be prepared for periodic pandemics – we will need yet another craft of dying. We have to re-think again, and fast.

Two crafts of dying

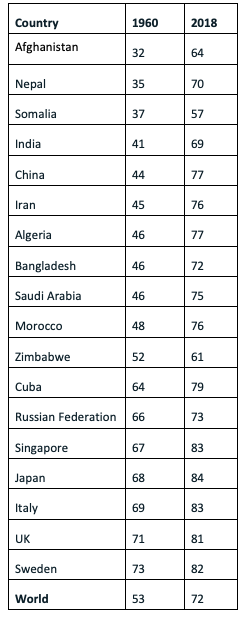

One of modernity’s greatest achievements has been to more than double the average lifespan to 80 from not much over 30. The global average is now over 70. Only countries experiencing civil war or ongoing political turbulence have been left behind. Before this demographic revolution, most people were carried off in a matter of days, or a week or two, from infectious disease – at any age, and often in infancy or childhood. In this pre-modern world, end of life policy was religious. Specified rites enabled the dying person to prepare for the next life; in Catholic Europe, the priest would be called and the last rites administered; Protestants would confess their sins and their faith and make their peace with God. Whether the dying person was aged seven or 70, what mattered was the moral quality of their life and their preparedness for heaven. A bad death was an unprepared death. Even in good health, the conventional parting ‘See you again’ would be suffixed by ‘if God wills’, for everyone knew that any parting could be the last.

Life Expectancy at Birth (Average number of years a newborn is expected to live if current mortality rates continue)

In the modern world, by contrast, how is someone with a terminal prognosis of cancer, Parkinson’s or heart disease to prepare for their demise? Even if they want a traditional religious rite of preparation, this takes but a few minutes, and they know they may live with their life-limiting condition for months or years. How then are they to live in the meantime?

Medicine by itself does not address this, but it was one of the key issues that concerned Cicely Saunders who founded the first modern hospice in 1967. In essence, her answer was to address the patient’s pain and symptoms sufficiently well that people could live the life they choose for the remaining months or years. Her practice was neither purely religious as in the middle ages, nor purely medical, but holistic. Now embodied in modern palliative care policy, Saunders developed this largely with patients dying slowly of cancer.

Cancer dying

Now cancer dying has some very particular features. First, whereas dementia, elderly frailty or significant heart disease will be terminal if nothing else kills you beforehand, how long you have cannot be predicted with any certainty. Though cancer prognoses are rarely exact, and can be wrong, generally it can be predicted that you are likely to have a few weeks, a few months, or a year or so. Second, full mental capacity is typically maintained until a few hours or days before death, so communication with family and health workers is fully possible. Third, in many highly industrialised countries, cancer services are now efficient and well resourced. These three features give any plans for your remaining months or years, a fair chance of coming to fruition - so long as you do not belong to a dysfunctional family or are severely disadvantaged in other ways, such as being homeless or in prison.

All this fits modern western notions of personal autonomy. In this modern craft of dying, the good death comes after a fulfilled life – the ideal of personal fulfilment is premised on general longevity and would have perplexed many pre-modern people. Today’s bad death is therefore not the spiritually unprepared death of the Middle Ages, but the untimely death of a child or young adult. The one thing in common between the medieval and the modern good death is to leave your material affairs in good order for your survivors.

Over the past couple of decades, the new ideal is being promoted for non-cancer dying. Those with dementia may have compromised cognitive capacity, but some principles of palliative care can still be applied. And to prevent the bad death of an accident or resuscitation that leaves you without autonomy in a vegetative state, advance directives are being promoted in which people in good health specify what life sustaining treatments they would not want in specified circumstances.

We need a third craft

Dying with COVID-19 is very different. Though someone with the virus may feel poorly for a few days, most recover without medical assistance. But a minority fall very sick so quickly that they cannot think straight and their autonomy is almost entirely compromised; if they manage to call for help, they find themselves entirely dependent on a struggling health care system. This is not predictable expected dying, but unpredictable unexpected dying; it entails days not of personal autonomy but of high dependency; dying not in communication but in isolation. Many elderly who fall very sick with COVID-19 live on their own and lack a mobile phone or the internet, so struggle to call for help. And for them, community nursing of the kind available for people at home with cancer is largely absent.

There are perhaps four kinds of COVID-19 dying. Dying in hospital, surrounded by ventilators and masked and gowned personnel. Dying in a care home which, intended to look after the vulnerable, may now render them far more vulnerable. Dying at home, isolated and alone. And dying at home of other conditions, not least stroke, because the patient fears calling emergency services or has no one to do it on their behalf. All present big challenges to holistic palliative care. We have to re-think the craft of dying, and fast.

What might this new craft look like? What might a new end of life care policy draw on? Given lockdown, it cannot rely on family members who may live hundreds of miles away. Given the numbers of the very sick and their infectiousness, it cannot rely solely on either high-tech medicine or resource-intensive palliative care without draining resources from the rest of the health system. It cannot rely entirely on already-stretched social care. Families, high tech medicine, palliative care and social care all have important roles to play, but are not enough.

Over the past decade or so, there has been considerable interest in the ‘compassionate community’ approach to end of life care, mobilising streets, neighbourhoods and workplaces to be there for those nearing the end of life, informally partnering with formal services. A well organised example is the Somerset town of Frome. Like dementia friends and the social model of disability, the aim is for the elderly, the frail and those nearing the end of life to continue to feel part of society’s rich mix rather than ignored, stigmatised or abandoned. But like palliative care, this approach to end of life care has been largely based on non-communicable diseases with an extended period of predictable dying. Compassionate communities are now sprouting all over the UK to support vulnerable people locked down at home, not least in my home town of Bath. This approach is great at providing shopping and mitigating loneliness, but may find it challenging if called to provide hands-on care for infectious home-bound patients.

Prevention

So, we are in dire need of a third ‘craft’ of dying. What though about prevention, about how to control the virus in the long term? Here there is encouraging news. The overall health policy framework that worked in the first era of infectious disease, and that works in the second era of non-communicable disease, will also work in the third era of novel pandemic viruses.

The formula? First, public health initiatives will work with COVID-19. If drains prevent typhus, clean air prevents respiratory diseases, and banning smoking in public places limits lung cancer, then lock-downs and school and workplace closures will limit the spread of this novel virus.

Second, behaviour change has a role to play, as in the past. If sleeping under a net prevents malaria, and limiting alcohol intake reduces the incidence of several diseases, then hand-washing and social distancing will help limit COVID-19, even after schools and workplaces re-open – or controversially in the case of Sweden, stay open.

Third, a high tech, low cost, widely available, pharmaceutical breakthrough is essential. Just as immunisation was crucial to controlling cholera and measles, and a few readily available drugs help control heart disease, so vaccination will be crucial in ending mass mortality from COVID-19.

This is not to say that a vaccine is guaranteed to be found, nor that current anti-COVID public health and behavioural measures are anything like perfect. It is to say that the formula, the policy framework – comprising public health, behaviour change, vaccination – is tried and tested. It is when prevention fails that we are in uncharted territory and need to develop new end of life care policies. We need a new craft of dying.

Are you a decision-maker in government, industry or the third sector responding to the coronavirus crisis? Apply now to our virtual Policy Fellowship Programme for access to University of Bath research and expertise. Learn more.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Responses

Very interesting Tony. https://www.carezee.co.uk/supportandinsights