Nick Pearce is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath. Joe Chrisp is a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen.

In recent years, the relationship between age and voting behaviour has become the focus of increasing political and public interest, particularly in the UK. Registration to vote and turnout rates are much lower for the young than the old, and partisan preferences now differ sharply by age. The 2017 and 2019 general elections saw significant demographic divisions in the electorate between older and younger voters, with those over 50 voting overwhelmingly for the Conservative Party, while the under-35s voted in large numbers for the Labour Party. Pronounced age divisions also marked voter preferences in the 2016 Brexit referendum: older voters delivered the narrow majority to ‘Leave’ the EU against the preference to ‘Remain’ of most younger voters.

These age divides are likely to be visible once again in ‘Super Thursday’s’ election results across the UK – with younger and middle aged voters in the cities and university towns backing Labour, the Liberal Democrats, Greens and the SNP, and older voters in post-industrial towns, prosperous counties and rural areas aligning heavily behind the Conservatives. In this blog, we offer some insights into these age divides, updating analysis from an earlier paper of ours on the political economy of older voters.

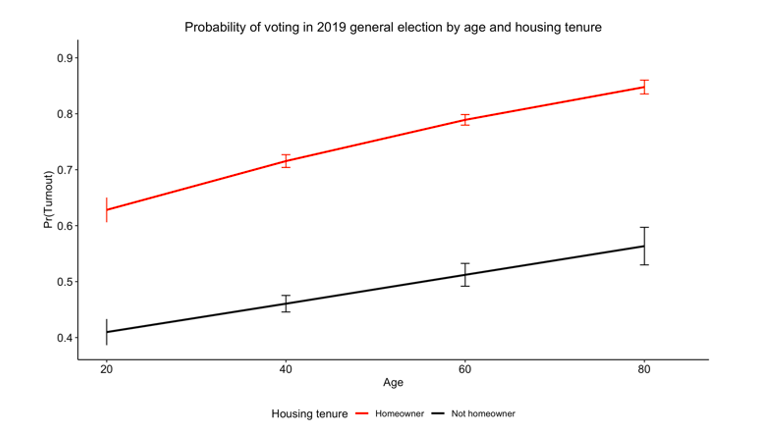

Age is strongly related to voter turnout, as the first graph below shows (unless otherwise stated, all the graphs in this blog use data from the British Election Study). There was a slight narrowing of the gap at the 2019 general election, with turnout falling for older voters and rising for the young – but it remains very wide.

We can also interact turnout by age with housing tenure. The probability of an 80-year-old homeowner voting is over 80%; that of a 20 year in rented accommodation is around 40%.

Voting by education level and age shows similar gradients. Turnout is very low for young people with GCSEs or lower qualifications – in stark contrast to older university educated people.

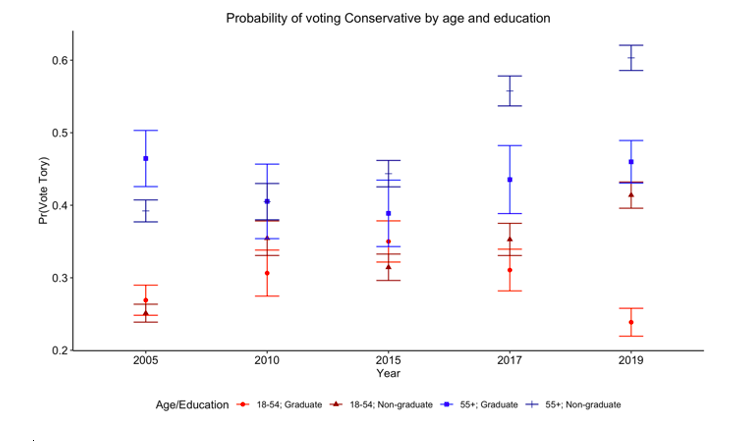

A significant part of the explanation of the Conservatives’ electoral success in recent years is that older voters not only turnout to vote in higher numbers than younger age groups but have shifted their partisan allegiances away from Labour. The probability of voting Conservative now increases considerably with age.

This support is not simply a function of education. Older graduates (55+) are more likely to vote Conservative than younger (18-54) non-graduates.

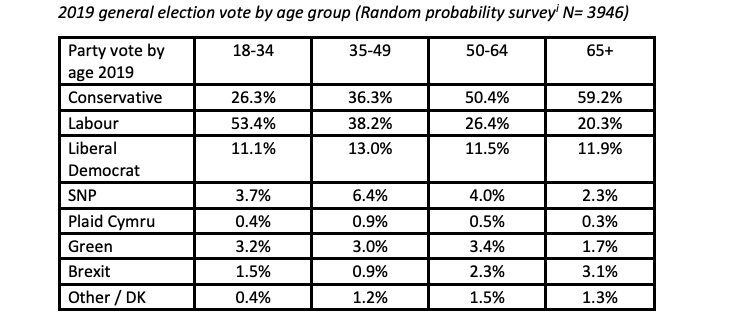

Age now structures the support of almost all of the UK’s main political parties, as the 2019 General Election results show in the table below. Older voters kept Scotland in the UK in 2014, just as they took the UK out of the EU. They are the bedrock of Johnson’s new electoral coalition.

Political scientists differ in their interpretations of this age divide. Proponents of values-based explanations argue that older generations hold socially conservative views, and vote against the liberal values of younger, university educated populations. Older voters are thus engaged in a ‘cultural backlash’ against social liberalism and increased ethnic diversity, rather than voting according to their social class interests or background.

Political economy explanations tend to resist dividing class and culture in this way and prefer to relate age differences in partisan preferences to the geographic and demographic divides thrown up by the transition from Fordist industrial societies to knowledge-based urban economies. The young and skilled cluster in ethnically diverse cities and university towns, and their liberal values reflect their work and social networks. Older people are ‘left behind’ in the culture and politics of the 20th century industrial economy.

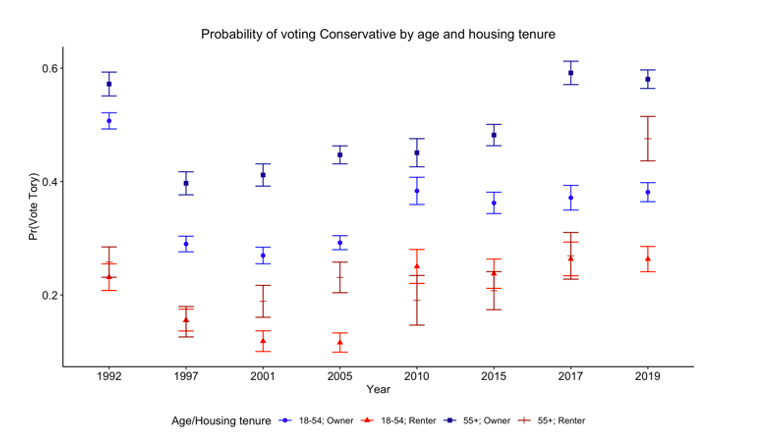

Our own contribution – which partly overlaps with important recent work by Jane Green and Raluca L. Pahontu on the relationship between wealth, risk aversion and voting for Leave or Remain - has focused on how older people have widely shared material interests in home ownership and other assets. Thus, when we interact the probability of voting Conservative by age with housing tenure, we see the importance of older homeowners to the party’s electoral support.

Interestingly, however, older renters swung towards the Conservatives in 2019, and became more likely than younger property owners to vote for the party for the first time in our data series. This doubtless reflects divisions over Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. But it must be remembered that over 75% of the 65+ age group are homeowners – and the gap between home ownership rates between young and old has widened considerably since the mid-1990s. The over 65s have a huge stake in the UK’s housing wealth and are thus at the electoral core of the ‘property-owning democracy’ and the politics it has spawned.

These arguments suggest that we cannot account for the age divide in political preferences simply by reference to values divides between the generations. Whilst such divides undoubtedly exist, it is important to examine the inter-relationship of identities and values with economic and social class formations – and to situate the interests and political preferences of older people in relationship to the structure of the British economy and the distribution of resources within it.

Evidence from the Bank of England, as well as research institutes such as the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation, has consistently found that older people have benefited disproportionately from both monetary and fiscal policy in the post-financial crisis era. Older homeowners have seen their housing and pension wealth increase as a result of Quantitative Easing, while the austerity enacted by the Coalition and Conservative governments of 2010-2019 gave relative protection to the social security entitlements enjoyed by older people, compared to those of the working age population. Despite the devastating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the health of older people, these patterns of relative economic disadvantage for the young and propertyless - particularly those from working class backgrounds - look set to persist.

[1] F2F-only estimates are all within 1% of the RPS estimates except for 18-34 & 35-49 Conservative vote share (23.6% and 38.6% respectively).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond