Why does public engagement with new technology matter? More to the point, why does public engagement with data matter? The collection and use of data isn’t new: in England, the state has been collecting data since at least the Domesday Book. People have been counting up things and making decisions based on those things for a long time. So why have perceived public concerns with things like data privacy and consent now, in 2016, become an issue? The answer lies in what that data can do.

Data analysis is no longer just about summing and recording. People (and machines) can create complex algorithms that seek to predict everything from flu trends to the likelihood of an individual committing a crime. These new kinds of data projects are broadly defined as ‘data science’, e.g. the use and combination of data in new ways. This science can leverage pre-existing ‘big data’ sets containing trillions of rows of data, like national hospital and store purchase records, to propose, inform and evaluate policy.

To engage different publics on ‘data science’, the Government Digital Service commissioned the Public Dialogue on Data Science Ethics. For the past few months, I have had the opportunity to observe these public consultations. The dialogues involved asking members of the UK public for their views on data science, asking specifically what lines government shouldn’t cross in its use and combination of data.

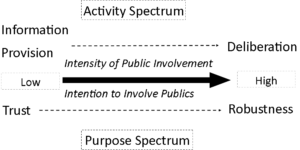

Engagement exercises like this one sit on a spectrum based on the intensity of active public involvement they entail (see the figure below). At one end, there is simple knowledge translation from government to citizen; at the other, full public participation and deliberation [3]. This typology also describes changes in how engagement is done in practice. Over the past few decades there has been a distinct shift from telling to asking publics about risk. However, engagement activities often blur this line. Arguably information provision must take place in consultation exercises, as it’s hard to imagine people caring about something they know nothing about. A more nuanced trend is the change in the purpose of engagement. Essentially, why should we do engagement? Knowledge translation is strongly related to securing some acceptable degree of trust, for example to improve public acceptance of a technology. More recently the purpose has shifted to a combination of building trust and robustness. Robustness involves publics shaping and improving new technologies and regulatory policies. This ‘purpose spectrum’ can tell us whether engagement will result in noticeable change.

The Public Dialogue on Data Science Ethics included both trust and robustness objectives. The dialogue’s aim was to reform the government’s Data Ethics Guidelines [4], which positions it as a deliberative exercise: one where public voices are given more influence in government activity. Each session included exercises based on identifying types of data and examples of how data science could be used in policy. The dialogue organisers used these exercises to translate complex and diffuse concepts, like machine learning, into accessible discussion prompts. They had to push participants outside the box in thinking about types of data, for example mobile phone GPS records and commercial ‘smart meter’ readings. This led to in-depth debates about the usefulness of data science in policy, which will inform changes to ethical guidelines.

The dialogue sits comfortably on the right side of both the ‘activity’ and ‘purpose’ spectrums. People aren’t given full deliberative power on data science, but it is anticipated that there will be tangible change and impact from the dialogue. However, this hides a major constraint in public engagement exercises, which is that the description of technology risks shapes or frames the discussion of them. Engagement activities necessarily involve information provision (telling) and consultation (asking). But ‘telling’ creates artificial discussion boundaries. If you present a major risk of data use as bias from inaccurate data, people’s discussion will inevitably revolve around that issue. The kinds of risks discussed included re-identification of individuals who were thought to be anonymous or lack of privacy in data handling procedures. At a more essential level, most publics would not immediately understand what ‘data science’ means. Their frame of reference for discussion will emerge from the definition given to them. It is challenging to probe for in-depth risk assessments when people have limited examples to draw from. By defining specific topics and examples of data science, engagement exercises are unavoidably restricted to certain views and presentations of data. The concerns and benefits people highlight are a reflection of the information they’ve been given. The dialogue may aim to be on the right side of the purpose spectrum but achieving that aim is difficult.

Organisers and different publics are both constrained by the limitations of public engagement. Engagement exercises tend to reflect a propensity towards restricted public influence. This means that the kinds of questions organisers can ask are also restricted. They cannot probe on policies and directives publics have no influence on to begin with, for example whether government should or should not work towards a model of ‘data-driven policy’. Greater public influence would require significant changes in technology risk governance and decision-making. It would require unravelling the constraint of balancing information provision with public engagement. How this could be done, either practically or theoretically, is up for debate.

This brings us back to the idea of purpose. If there is such a limited role for public voices, why bother? Arguably, for the time being, what’s important is the aim. The Public Dialogue on Data Science Ethics aimed, and did, include public opinions in the future of data science in policy. This lends credence to the idea that new kinds of data are a public matter and that people deserve a voice, even if for now, it is limited to a specific set of discussions. As we go forward with engaging publics in data science, we can move beyond managing concern. Conversations can be broader and more inclusive.

Emily Rempel is an interdisciplinary PhD student in the Department of Psychology and the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Bath. She is working with the Cabinet Office’s Government Digital Service on the Public Dialogue on Data Science Ethics.

[1] http://www.domesdaybook.co.uk/

[3] Rowe, G., Frewer, L. J., & Frewer, L. J. (2015). A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms, 30(2), 251–290. http://doi.org/10.1177/0162243904271724

[4] https://data.blog.gov.uk/2015/12/08/data-science-ethics/

Respond