Dr Alim Baluch is Teaching Fellow in German Politics & Society at the University of Bath's Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies.

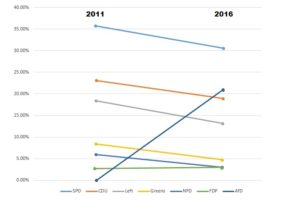

In July 2016, Germany was struck to the core by a wave of terrorist attacks; two were carried out in the name of radical Islam, and the most devastating one, the Munich massacre, in the name of right-wing extremism. Islamophobia and attacks on refugee homes are on the rise as right-wing Germans fear for their imagined national character. In last week’s state election in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Merkel’s home state), the right-wing xenophobic party Alternative for Germany (AfD) amassed a larger share of the votes than Merkel’s CDU. 21% had voted for a party which states in its program that Islam does not belong to Germany.

Many cosmopolitan Germans are deeply troubled by the current shift to the right – even among their Turkish neighbours and friends, many of whom support president Erdoğan, whose religious conservatism has turned into right-wing authoritarianism. There are even German Turks and former refugees who reproduce anti-refugee rhetoric, expressing fear that the recent arrivals may spoil the reputation of all Muslims.

Muslims in Germany are concerned about the anti-Muslim discourse, the fear of further jihadist attacks with potentially devastating consequences for their daily lives and, maybe most terrifyingly, young teenagers running away from home to Syria in order to join IS. The enemy is out there and, potentially, in one’s own family. Trust is good, but surveillance is better; there have been numerous cases of Muslim parents reporting their children to the police.

Germany is witnessing a vicious circle of fear and hostilities that can be subsumed under the notions of Islamism and Islamophobia (although both terms are not without critique, they are nonetheless used in this piece to make basic assumptions accessible). While xenophobia in Britain, for instance, is much more diverse, given the strong fear of Central and Eastern European migrants, German xenophobia is increasingly focussed on Islam, implicitly imagined as a coherent social and ideological block.

This blog post seeks to embed these developments into the theoretical framework of the Iranian sociologist Dawud Gholamasad (former Chair in sociology at the University of Hannover, who also taught at Oxford University between 1999 and 2003). The entire theoretical edifice, though not the historical background, of this post is based on his work – particularly on a seminal piece written in German and published on his website.

In the following, I will use Gholamasad’s process sociological perspective to discuss why hateful ideology is so attractive to a specific form of mental suffering that cannot be explained by individual trauma and childhood experience alone. History matters; culture matters; and religion matters – but not in the naively simplistic way Islamophobes have in mind.

I will attempt to make Gholamasad’s theoretical arguments more accessible by delving into history and the long-term developments that have led to an ideology of lost superiority. These long-term historic developments are not only a sequence of facts but have a profound impact on self-worth regulations of individuals in various societal settings. Finally, I will return to the context of recent violent attacks in Germany that, I will argue, are based on reasserting the remembered ideologies of superiority.

Gholamasad points out that the condition of possibility (not the cause) of Islamism – as well as Islamophobia – lies in self-worth related cognitive schemes of egocentric human beings. In other words, we unconsciously assess the differential between the apparent reality and the ideologically self-reinforcing ideal.

Islamism and Islamophobia can be best understood as aspirations to narrow the painful gap between reality and the imagined ideal. The reader may be aware of the more-or-less conscious assumptions of Western/white superiority that often underlie political discourse. What is less well-known is the Islamic version of implicit supremacy, which is rooted in an inherited sense of entitlement to superiority.

Certainly until the fall of Al-Andalus in the late 15th Century, the Muslim world had a strong sense of superiority over the non-Muslim world – including Europe. Indeed, the big caliphates of the Middle Ages were superior in natural sciences and medicine, and – just like Europe in the following centuries – that Islamic scientific superiority and military power also translated into the cynical exploitation and slavery of the 'others'. From the 9th Century on, 'white' Europeans were taken as slaves. But the reality was much more complex than this may sound.

The Arab rulers of Andalusia showed little interest in expanding their European power base further north. This allowed for more-or-less peaceful trade relations with Northerners who supplied them with slaves caught in what is now Northern Germany. The target area of slave hunters moved further east in the following two hundred years. Initially, these slaves were often Saxons who had not yet converted to Christianity (ironically, their British descendants would later create the biggest slave trade in human history).

The self-perception of Muslim supremacy had profound implications that cannot be underestimated. To further illustrate this point, we should take a step back and view the macro picture of the early history of Islam, a religion founded by members of seemingly insignificant desert tribes. This early period was characterised by a rapid expansion over half of the inhabited Eurasian world, a success which must have even surprised the followers of Islam themselves.

To understand Gholamasad’s notion of an inter-generationally remembered entitlement to superiority (there is also a British and a Turkish variety), picture an Ummayad caliph asking himself: “How on earth is it possible that we are so successful?” The answer seemed obvious: “Allah wants it. We have the right religious belief. We are unstoppable.”

This sense of superiority was engrained in the self-worth of the Muslim elite and even the wider Muslim population could tap into the self-worth supply which comes with the common group charisma of the ummah. The remembered claim to superiority as a condition of possibility for maintaining self-worth was passed on and on from one generation to the next. This superiority was manifest in the Muslim world’s ability to control the non-Muslim world, more so than vice versa. By the 15th Century, however, power relations between what was imagined as Islam and what was imagined as Christian Europe had shifted towards the latter. Christian kingdoms and empires had attained scientific and military superiority over their Muslim rivals and this superiority would increase dramatically over the coming centuries.

The disillusion of the Muslim world

The reality of the inferiority of the Muslim world in terms of control vis-à-vis the Western world did not sink in immediately. It is this delay which Norbert Elias (1991) calls the drag effect of the social habitus, ie. when the cognitive patterns and self-worth regulation of individuals have not caught up with political and social developments. This drag effect can lead to emotional pain and social conflict.

The realisation of Western superiority was further impeded by an Ottoman Empire pulling above its weight and finally navigating its slowly sinking ship between the rocks of far superior European empires. Surprisingly, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire – which was the last big caliphate (and thus main representative of Sunni Islam) – in the 1920s came as a shock to the literate Muslim world. The cleavage between the self-worth oriented demand for superiority and the bleak political realities of the 20th and 21st Centuries generated the potential for an emotional pain that was exacerbated by Western military interventions terrorising entire nations. The “Why are we so successful?” was turned around into “What happened to us? Why are we so inferior?”

Given the traditional fatalism of Islam, the answer had to be: “Allah wants it. He is punishing us.”

The intergenerational system of self-worth regulation was malfunctioning. But if God was punishing Muslims then the question was why, and it was radical Islam which presented the most impactful answer: “Because we have abandoned him. To regain our vested right, we have to return to the old ways.”

The end of the Ottoman Empire and its secular modernisation shattered all illusions. The painful powerlessness of the 20th Century was felt by a section of the Muslim world that was literate, religious and reflected upon the new political realities perceived as a lost power struggle between Islam and Christendom. It is therefore not necessarily a coincidence that political Islam was born in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. It was in the periphery of the fallen empire that the Egyptian school teacher Hassan al-Bannah established a religious political movement, the Muslim brotherhood, in the 1920s.

Like any other political movement, political Islam is chiliastic. This means that it is based on the expectation of a paradise which is yet to come. In secular ideologies, this paradise takes the form of a perfect world. For national socialists, for instance, this would be the 1000-Year Reich. All the brutality and mass murder would be committed to bring about a just and peaceful world, a world that can only be established once the enemies are exterminated. This is not to say that chiliasm is necessarily pursued by violent means. Environmentalism and communism are chiliastic movements as well. The struggle can take more or less peaceful forms.

According to Gholamasad, traditional Muslim chiliasm is quietist, ie. fatalistic. The world may be unjust and, for some unknown reason, Allah lets Christians and atheists control this modern world – but there is nothing one can do about it. Accordingly, everything is Allah’s will. This attitude was conducive to augmenting self-worth gratification in a time of expansion and superiority and boosted the identification with Islam as a superior political project even further. However, the degree of emotional attachment to Islam as a relational category vis-à-vis a non-Islamic world indicates the potential for emotional suffering in a world in which this metaphysical object of identification is in decline. Since the 1920s, quietism has been notably challenged – with far-reaching consequences.

Chiliastic quietism shifted towards chiliastic activism. Thus, what is often referred to as Islamism or radical Islam is a modern phenomenon. The new activist Islam considers the old quietist passivity as precisely the reason for the dire state of affairs. Quietism can therefore be perceived as a sin. The fatalistic Muslim is hence seen as a non-Muslim, an obstacle or even an enemy who raises children in a counter-productive way.

It is no longer good enough to wait for the afterlife; a just world according to Allah’s will has to be fought for. No sacrifice is too big. The shameful passivity of the forefathers, it is argued, has allowed the Muslim world to be taken over by corrupt and sinful rulers, making the homelands vulnerable to Western looting of natural resources and military operations (to use this euphemism) that have killed hundreds of thousands. IS supporters consider organised violent activism to be the only way to reverse the emotionally painful downfall and humiliation of the Islamic world and avenge the military crimes of Western governments. Western military operations are the conditions of possibility but not the cause of IS-style radicalism. They further fuel and radicalise the still-ongoing shift towards chiliastic activism, and encourage an openness to ever more violent means.

A Perfect Storm of Necrophilic Self-worth regulation

"The time has passed when you would come to our lands and kill our women and children. God willing, you will be attacked in every street, every village, every city and every airport.”

Source: Zeit.de [translation].

17-year-old refugee Riaz Khan Ahmadzai from Afghanistan had videotaped himself announcing violence in the name of Daesh. He was not just a lone wolf; he was indeed in contact with the infamous organisation that encouraged him to use a vehicle as a weapon. But the teenager reminded his contacts that he did not own a driver’s license. Instead, he informed them of a different plan, namely that he would enter a train with a knife and a hatchet to attack the first passengers he would encounter – whoever they may be. The random victims of 18 July happened to be a family of tourists from Hong Kong. The 62-year-old father and his daughter’s boyfriend suffered life-threatening injuries. After stopping in Würzburg, the attacker left the train. Upon encountering a 51-year-old woman walking her dog, he hit her in the face with the hatchet. Shortly afterwards he was fatally shot by the police.

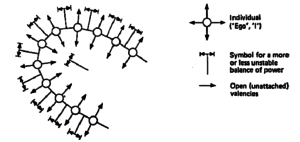

Process sociology helps us to fathom the emotional pain of violent extremists. It demonstrates that our mind is a communication system in a dynamic network of communicative relations. Our thoughts, emotions and conversations (ie. our individualised social habitus) can only be understood as self-worth oriented processes. Everything we do is relational; it is directed at others. Gholamasad’s research is based upon Elias’ concept of figuration (Elias 1978, 1991). Humans are fundamentally directed towards others and seek to attach valencies, which can be understood as emotional needs. These valencies are attached through establishing emotionally rewarding relationships with others, a network of family, friends, colleagues and maybe even imagined entities.

In a world that is perceived as inherently unjust, a world in which a young person is denied a gratifying network of self-worth inducing emotional bonds (ie. attaching valencies), he/she is likely to be more receptive to a narrative of injustice done to a group that is imagined to be entitled to supremacy. The discrepancy between the group’s reality and its rightful place taps into the emotional suffering of its potential recruits.

If the imagined order cannot be restored, the martyr’s contribution can be perceived as a meaningful way of tackling emotional suffering and injustice and helping the imagined ‘we group’, whether this may be the ummah, the Aryan race or another group. Extreme violence and upholding self-sacrifice as a virtue is an indicator of the degree of painful incongruence between the ideal and reality. In this respect, the Islamist narrative is different from – but also similar to – the national socialist narrative.

The Northern European nativism of Anders Breivik corresponds to the regional nativism of the Taliban and the pan-Islamic nativism of IS, a nativism based on the idea that the we group is under attack by intruders who are dangerous and destructive and can only be defeated by ruthless determination. Any devoted Sunni Muslim can be part of this we group, whether it is an Indonesian activist or a German convert.

Another dichotomy which helps explain the social psychological processes that lead us to hateful ideology and death cults is the distinction between necrophilia and biophilia. Necrophilia is a general affinity to death and destruction; biophilia is the affinity to a life of stable emotional bonds of positive reinforcement with fellow human beings as well as non-human nature.

Only a few days after the attacks of Munich and the Würzburg attack, the suicide bomber and Syrian refugee Mohammed Daleel – who injured 15 in the idyllic Bavarian town of Anspach – shocked Germany to the core. His story offers plenty of material to be exploited by the far right. He was staying in a hotel, and he was a refugee in contact with Isis. But the German TV audience also learned that he was mentally unstable and had previously attempted to commit suicide. The 27-year-old was about to be deported to Bulgaria according to the Dublin Agreement.

IS is inherently necrophilic, as are right-wing extremist fantasies of leaving refugees to drown in the Mediterranean – cynically suggesting that this may save lives in the long run. The worst possible outcome of the refugee crisis for Germany is a mutually reinforcing escalation of pars pro toto distortions, ie. mistaking a dangerous minority as typical representatives of a vague category of people encompassing millions.

The distorted view of “the West” is so focused on anti-Islam rhetoric and violence that all Westerners are part and parcel of an anti-Islam block. By that logic, all Western civilians are fair game. Accordingly, they are believed to hate Islam – and they voted for governments that supported war in Libya and Syria.

Likewise, all Muslims are viewed as followers of a barbaric ideology because the Quran itself is conceived of as inspiring the faithful to be violent, while conveniently ignoring similar passages in both testaments of the bible. These oversimplifications ignore the much more interesting change in the structure of Islamic chiliasm and emerging new-wave activist neo-Nazism, as seen in the extreme examples of Anders Breivik and the terrorists of the National Socialist Underground (NSU) who murdered mainly Turkish immigrants across Germany.

The Munich attacker Ali David Sonboly whose Iranian descent was neatly incorporated into his self-perception as being a German of truly Aryan descent (given that the Aryan people actually live in Iran) was a right-wing extremist. Sonboly was a bullied teenager from Munich who fatally shot 9 people who were of migrant background before committing suicide.

This example demonstrates not only the destructive potential of unattached valencies, but also that his emotional pain was susceptible to an ideological vessel which could just as well have taken the form of radical Islam.

It is therefore shallow and misleading to consider ideology as a cause for violence; violence does not need an ideology. There is no such determinism. The various chiliastic narratives of denied greatness and injustice which can only be overcome by necrophilic activism are merely options amongst a wider array of possibilities, of which some are more applicable than others according to the individual case. Empirical research is needed that focuses on the underlying emotional demand.

Given that many Syrian refugees are deeply traumatised, building a healthy biophile figuration of affective bonds in an alien environment while overcoming trauma is an important challenge. It is one that demands help from the state as well as citizens that goes far beyond the initial willkommenskultur.

Unfortunately, many German citizens already feel disenfranchised themselves by the increasing casualisation of the job market and low pay at a time when rents are already rising dramatically – even without the recent refugee immigration. Following the terrorist attacks, more and more Germans are turning away from their new neighbours. Young Germans are becoming more vulnerable to self-worth regulation based upon right-wing nativism.

In light of this, it is crucial that Germany invests a great deal of resources into therapy for traumatised refugees, language training, social integration and transforming the job market to benefit everyone living in Germany – including the already existing German precariat. This might just help prevent viewing refugees merely as potential terrorists and a further descent in the race to the bottom.

The more Europeans feel threatened in their self-worth, be it by the European Union, immigration, austerity or disintegration of their emotional bonds, the more they are likely to support ideologies of threatened superiority. Viewing Islam as primitive and barbaric provides a powerful and self-worth producing narrative which further threatens the healthy self-worth regulation of Muslims. A vicious circle indeed.

Sources:

Elias, N. 1991. The Society of Individuals. London, Basil Blackwell.

Elias, N. 1978. What is Sociology? New York, Columbia University Press.

Gholamasad, D. 2015. Wie und warum sich Islamismus und Islamophobie gegenseitig als de-zivilisierende Aspekte der Demokratisierung in Europa gegenseitig hochschaukeln. Gholamasad.jimdo.com.

Respond