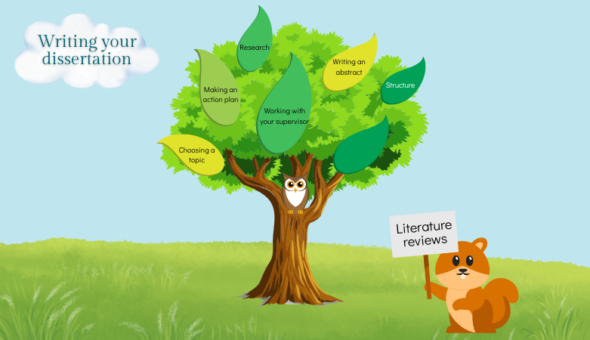

In this post, we look at the structural elements of a typical dissertation. A well-structured dissertation should be enjoyable to read. It should be logical and coherent, and your argument or line of reasoning should be convincing and easy to follow. Of course, this is easier said than done, so it is vital you spend time planning your structure to ensure success.

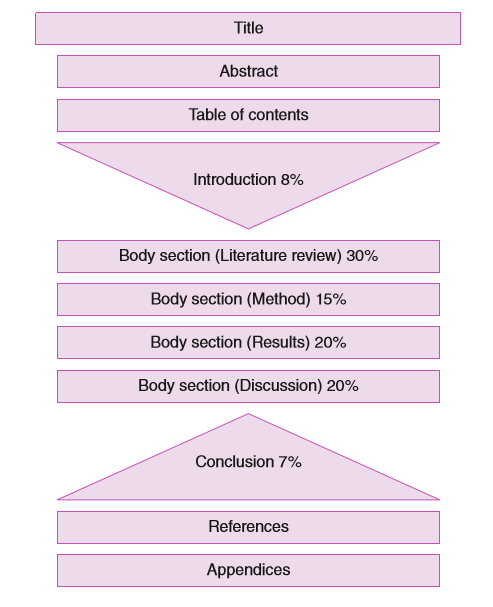

Your department may wish you to include additional sections but the following covers all core elements you will need to work on when designing and developing your final assignment. The table below illustrates a classic dissertation layout with approximate lengths for each section.

Hopkins, D. and Reid, T., 2018. The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guide to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University. Sage.

Planning your structure

It can be difficult to work out where to start designing the structure of your dissertation, with so many elements, sections and ideas to consider. The starting point is your research question(s). This is the glue that sticks all the sections and lines of reasoning together. Your research question(s) will provide the logic and coherence you need to maintain throughout your dissertation.

Next, break down planning tasks into smaller, achievable parts. So your process could look something like this:

1. Make a list of all the elements and ideas that you need to include.

For example:

- Chapter headings

- Notes about analysis

- Ideas for graphical representation

- Ideas for further research

2. List the main chapters in the order they will appear.

3. Under each chapter heading, list important sub-headings.

For example, your literature review chapter will include several different segments. For each of these you could add a sub-heading based on specific content. Your final sub-heading may be a mini conclusion segment that brings the chapter to a close.

4. Under each sub-heading, list the main content.

Create sub-sub-headings if needed and ensure that all the content you want to include has been allocated a place.

5. Slot in ideas, references, quotes, clarifications, and conclusions as they occur to you, to make sure they're not lost.

6. Check your labelling is consistent and that your structure represents a logical and coherent overview of your research study.

All chapter headings and sub-headings should link directly to your research question.

7. Check your structural plan with your supervisor.

You should also consider gathering feedback from friends and classmates. It is highly likely they will see something you've missed.

Title

Your title should be clear, succinct and tell the reader exactly what your dissertation is about. If it is too vague or confusing, then it is likely your dissertation will be too vague and confusing. It is important therefore to spend time on this to ensure you get it right, and be ready to adapt to fit any changes of direction in your research or focus.

In the following examples, across a variety of subjects, you can see how the students have clearly identified the focus of their dissertation, and in some cases target a problem that they will address:

An econometric analysis of the demand for road transport within the united Kingdom from 1965 to 2000

To what extent does payment card fraud affect UK bank profitability and bank stakeholders? Does this justify fraud prevention?

A meta-analysis of implant materials for intervertebral disc replacement and regeneration.

The role of ethnic institutions in social development; the case of Mombasa, Kenya.

Why haven’t biomass crops been adopted more widely as a source of renewable energy in the United Kingdom?

Mapping the criminal mind: Profiling and its limitation.

The Relative Effectiveness of Interferon Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C

Under what conditions did the European Union exhibit leadership in international climate change negotiations from 1992-1997, 1997-2005 and 2005-Copenhagen respectively?

Abstract

The first thing your reader will read (after the title) is your abstract. However, you need to write this last. Your abstract is a summary of the whole project, and will include aims and objectives, methods, results and conclusions. You cannot write this until you have completed your write-up. Read this six point checklist for writing an abstract.

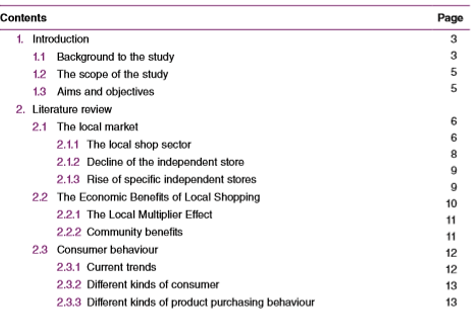

Contents

Your dissertation needs to flow logically from beginning to end. To help the reader navigate your content:

- Sections need to be numbered

- Sub-sections also need to be numbered

- Headings and subheadings must be consistent in style and grammar

Your contents page should therefore look something like the following (although there will be variations depending on the subject and your discipline)

Hopkins, D. and Reid, T., 2018. The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guide to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University. Sage.

Introduction

Your introduction should include the same elements found in most academic essay or report assignments, with the possible inclusion of research questions. The aim of the introduction is to set the scene, contextualise your research, introduce your focus topic and research questions, and tell the reader what you will be covering. It should move from the general and work towards the specific. You should include the following:

- Attention-grabbing statement (a controversy, a topical issue, a contentious view, a recent problem etc)

- Background and context

- Introduce the topic, key theories, concepts, terms of reference, practices, (advocates and critic)

- Introduce the problem and focus of your research

- Set out your research question(s) (this could be set out in a separate section)

- Your approach to answering your research questions

Literature review

Your literature review is the section of your report where you show what is already known about the area under investigation and demonstrate the need for your particular study. This is a significant section in your dissertation (30%) and you should allow plenty of time to carry out a thorough exploration of your focus topic and use it to help you identify a specific problem and formulate your research questions.

You should approach the literature review with the critical analysis dial turned up to full volume. This is not simply a description, list, or summary of everything you have read. Instead, it is a synthesis of your reading, and should include analysis and evaluation of readings, evidence, studies and data, cases, real world applications and views/opinions expressed. Your supervisor is looking for this detailed critical approach in your literature review, where you unpack sources, identify strengths and weaknesses and find gaps in the research.

In other words, your literature review is your opportunity to show the reader why your paper is important and your research is significant, as it addresses the gap or ongoing issue you have uncovered.

Method

You need to tell the reader what was done. This means describing the research methods and explaining your choice. This will include information on the following:

- Are your methods qualitative or quantitative... or both? And if so, why?

- Who (if any) are the participants?

- Are you analysing any documents, systems, organisations? If so what are they and why are you analysing them?

- What did you do first, second, etc?

- What ethical considerations are there?

It is a common style convention to write what was done rather than what you did, and write it so that someone else would be able to replicate your study.

Results

Here you describe what you have found out. You need to identify the most significant patterns in your data, and use tables and figures to support your description. Your tables and figures are a visual representation of your findings, but remember to describe what they show in your writing. There should be no critical analysis in this part (unless you have combined results and discussion sections).

Discussion

Here you show the significance of your results or findings. You critically analyse what they mean, and what the implications may be. Talk about any limitations to your study, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of your own research, and make suggestions for further studies to build on your findings. In this section, your supervisor will expect you to dig deep into your findings and critically evaluate what they mean in relation to previous studies, theories, views and opinions.

Conclusion

This is a summary of your project, reminding the reader of the background to your study, your objectives, and showing how you met them. Do not include any new information that you have not discussed before.

References

This is the list of all the sources you have cited in your dissertation. Ensure you are consistent and follow the conventions for the particular referencing system you are using. (Note: you shouldn't include books you've read but do not appear in your dissertation.)

Appendices

Include any extra information that your reader may like to read. It should not be essential for your reader to read them in order to understand your dissertation. Your appendices should be labelled (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B, etc). Examples of material for the appendices include detailed data tables (summarised in your results section), the complete version of a document you have used an extract from, etc.

Getting started

It's really important that you start writing up your dissertation as soon as possible. Don't wait until your research is completed, as the write up may become too intimidating or overwhelming. It may not be pretty at first and it will probably need revisions further down the line, but writing is all about practice and the more you write the better and more expert you will become. At this stage, don't worry too much about your word count and the size of each section. It's more important to get started on the process and you can always edit upwards or downwards as you go along.

Your supervisor may also wish to see your work in progress, or you may have an interim assessment to complete. They may be looking for development and improvement so self-critique is also a critical element in the write-up process.

Further support

If you'd like some further support on writing your dissertation, we offer 1:1 tutorials both online and in-person. Tutorials are available throughout the summer, and slots become available 14 days in advance. You can see what's available, and book a tutorial, in MySkills.

Responses

I am finding this helpful. Thank You.

It is very useful.

Glad you found it useful Adil!

I was a useful post i would like to thank you

Glad you found it useful! 🙂