Dr Iulia Cioroianu is a Prize Fellow in the Institute for Policy Research (IPR), University of Bath.

Background

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded over the past months, digital tools, online platforms and social media became an integral part of the strategies used by governments, private companies, households and individuals to adjust to sudden changes in work, schooling, care, and household management.

Increased social distancing policies were followed by a generalised lockdown, imposed in the UK over a month ago, and in this context, the role of online local communities has peaked. Local authorities have been working online alongside volunteer organisations and individuals to support the vulnerable, coordinate initiatives to help those in need, and support local businesses. Existing local working groups and charities have seen a surge in interest and new local initiatives have been established to deal with new and increased demands for care and support. At the same time, the weight of the public response at the community level has concentrated on social media.

Similar ad-hoc online crisis communities have been documented in other contexts, and research shows that they can be used as complementary support tools by government crisis management teams. In many of these settings, there is a reported lag between the swift community response enabled by digital tools and social media, and the ability of local and national authorities to incorporate these new resources in their crisis response efforts, and most importantly, retain them and incorporate them into their long-term crisis management and general operation plans.

Beyond the time constraints inherent to crisis situations, there is a general gap in digital infrastructure which reduces the ability of local authorities to map the dynamic crisis environment and identify available resources within a very short timeframe. While some local authorities have made managed to incorporate a range of digital elements into their COVID-19 management strategies, the general response does not seem to take full advantage of the possibilities afforded by the use of social media to understand, coordinate and integrate online communities within the crisis response toolkit of local authorities.

Focusing on online reactions to the COVID-19 crisis in the Bath and North East Somerset (BANES) area, I address some of these issues by analysing the social media landscape at the level of the local community over the past two months, identifying the ways in which the crisis has been reflected in online information patterns, and studying the network of local actors involved in digital community formation efforts.

Data and methods

Facebook and Twitter data has been collected over a period of nine weeks, between the 14th of February (when the UK recorded 10 COVID-19 cases) and the 21st of April 2020. This included 19,000 tweets of local news outlets, their retweets and replies, along with the tweets of local authority accounts and news pages disseminating information about the local area.

Tweets including four hashtags popular among these accounts (#Bath, #BackingBath, #BathTogether and #CompassionateCommunity) were also collected. Facebook data collection resulted in 2450 publicly available posts on the pages of 20 local news and local authority pages, as well as publicly available aggregate measures from popular local Facebook groups. Quantitative text analysis was used to study the content of the posts, and network analysis was used to visualise social media networks and identify key actors.

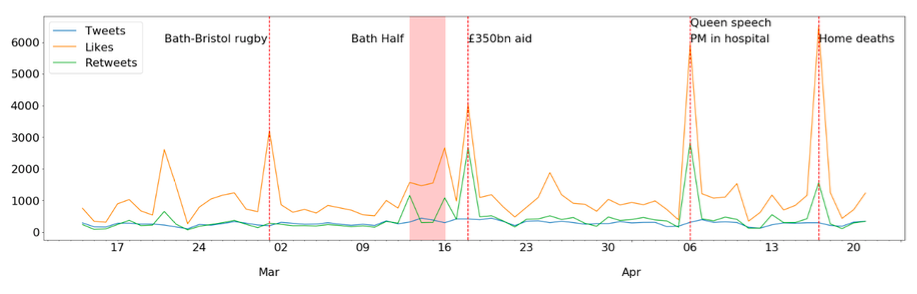

Local social media landscapes

Following the government’s announcement of lockdown measures on the 23rd of March 2020, local community engagement has increased both on Twitter and on Facebook. Fig. 1 shows an increase in Twitter activity over the last month. Local activity follows national trends – with peaks for the Queen’s speech and Boris Johnson’s hospital admission on the 6th of April, as well as the government’s 17th of March announcement of a £350 aid package for businesses – but it is also driven by some of the local events, such as the Bath Half Marathon which generated a bout of social media engagement both before and after the event. Similar trends have been observed for Facebook local posts.

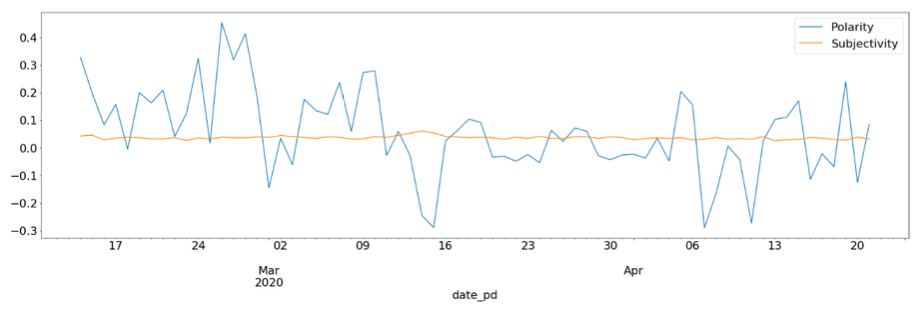

At the same time, the period after the lockdown saw a marked change in the overall sentiment of content posted locally on social media. While the level of positive messages remained relatively constant before and after the middle of March, negative sentiment was more pronounced after, resulting in the patterns of overall subjectivity (the extent to which the text captures emotions) and polarity observed in Figure 2.

Positive values of the polarity measure correspond to positive sentiment, while negative values correspond to negative sentiment. The pandemic has had a strong impact on social media sentiment, and the encouraging messages around community mobilisation efforts evident in the second half of the analysis do not compensate for the overall negative sentiment.

Topic analysis

The topics discussed locally on social media indicate the main issues of interest in the community, but also allow us to analyse differences in the ways social media platforms are being used, and identify potential avenues for integrating local authority, public and volunteer community support efforts based on the content generated.

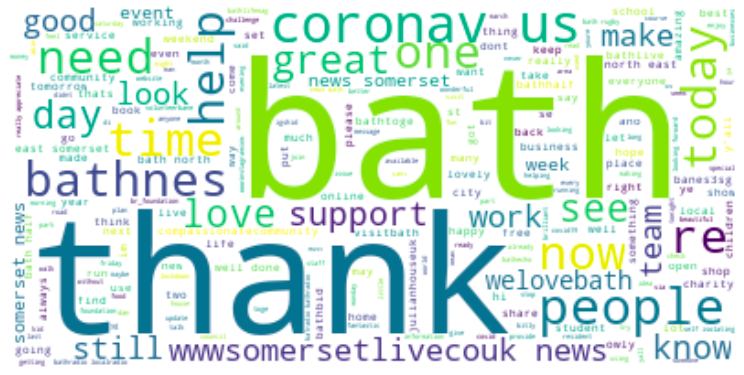

Figure 3 presents the most relevant words in our aggregated corpus. An initial hypothesis based on existing research about differential intended usage across social media platforms would be that there will be discrepancies in the topics discussed on Facebook and on Twitter.

In aggregate form, few differences can be observed for the original posts of local authority, news and information pages – a lot of the content from these sources is replicated across both platforms and the discussion is overwhelmingly centred around the general theme of the pandemic. However, closer inspection of the topics within each data source reveals differences related both to content, and to platform usage patterns.

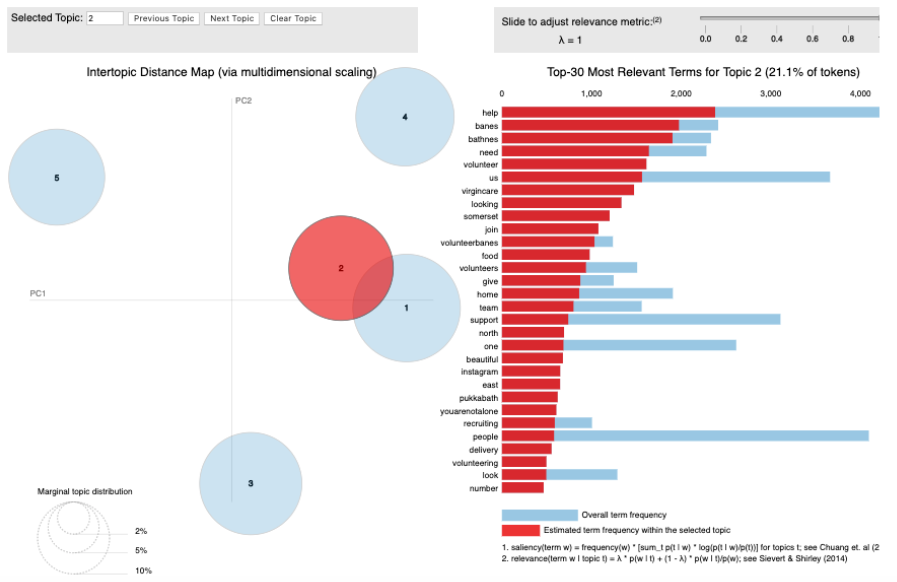

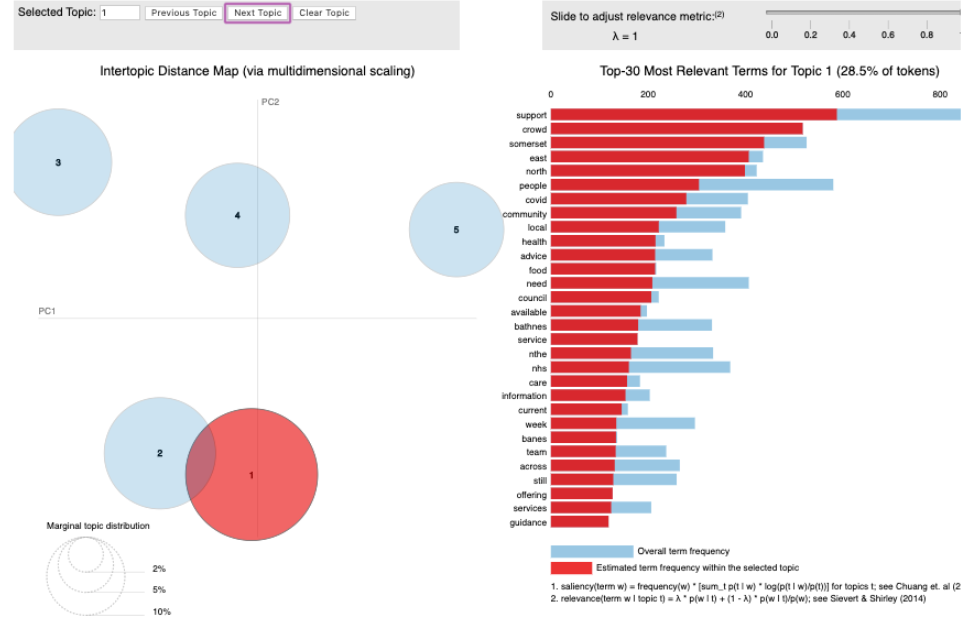

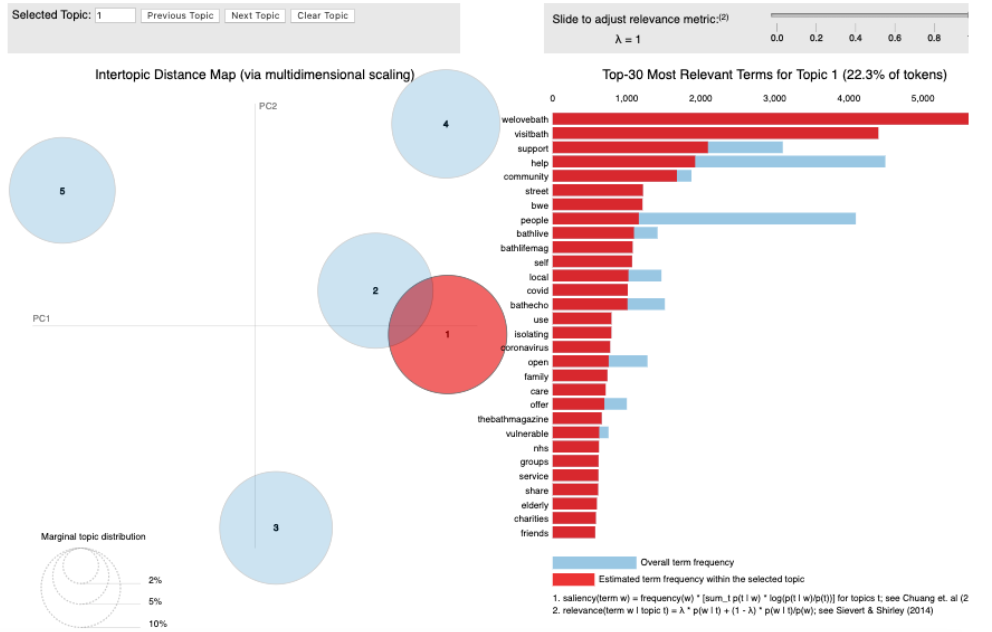

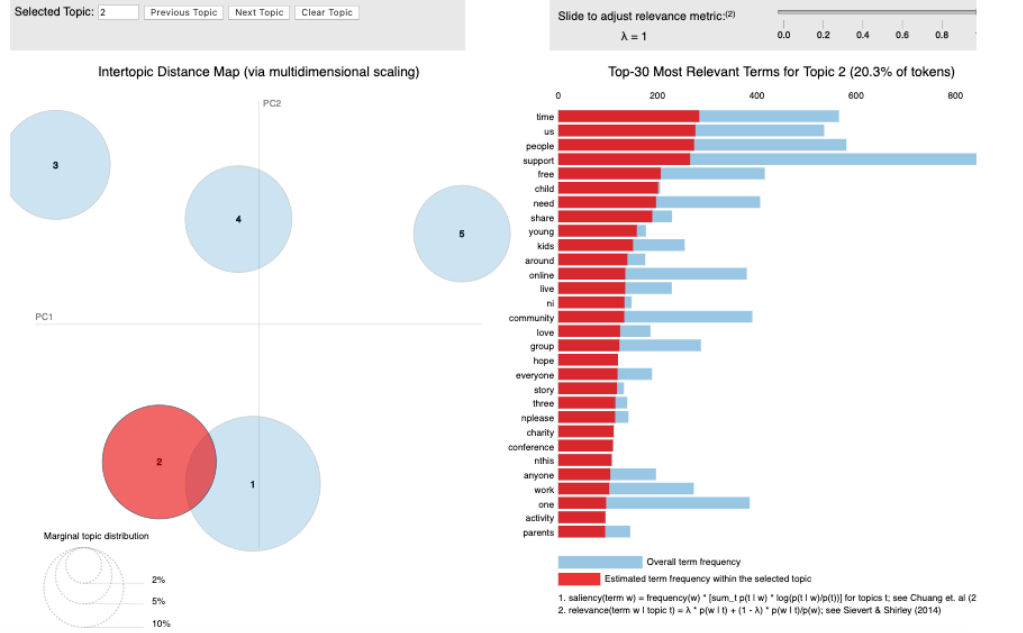

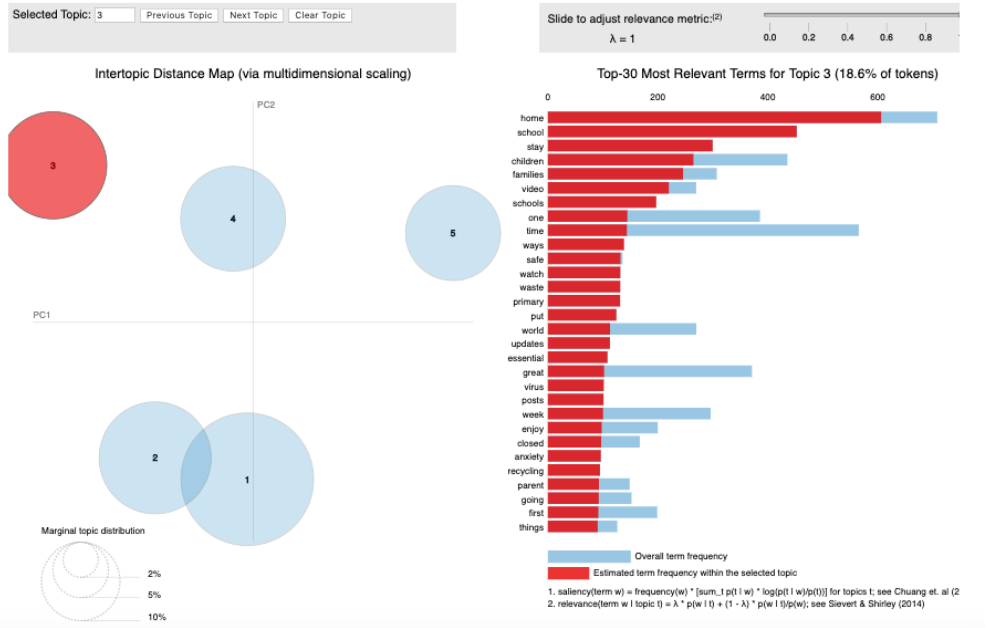

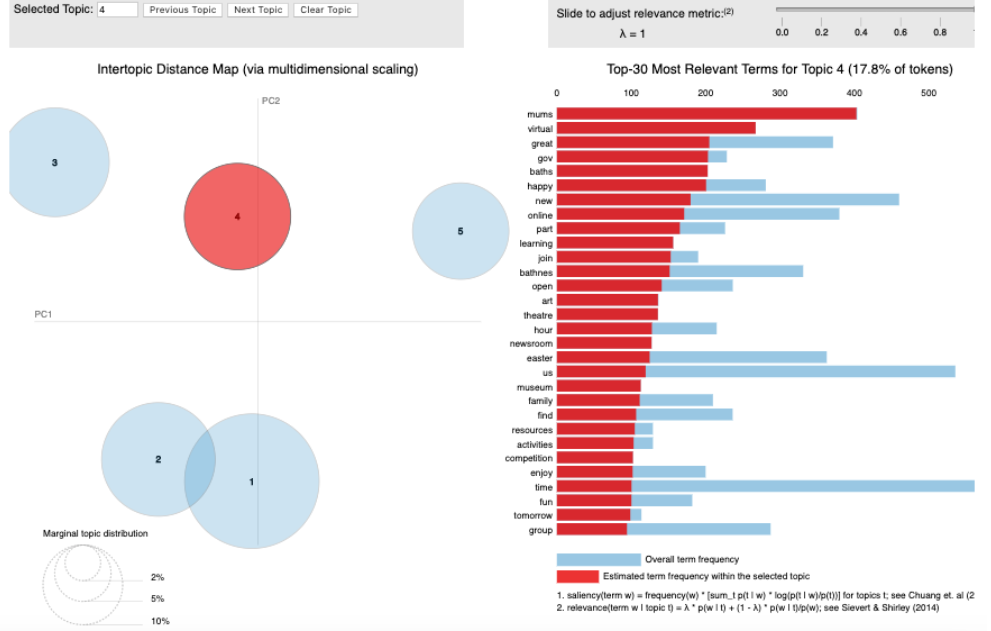

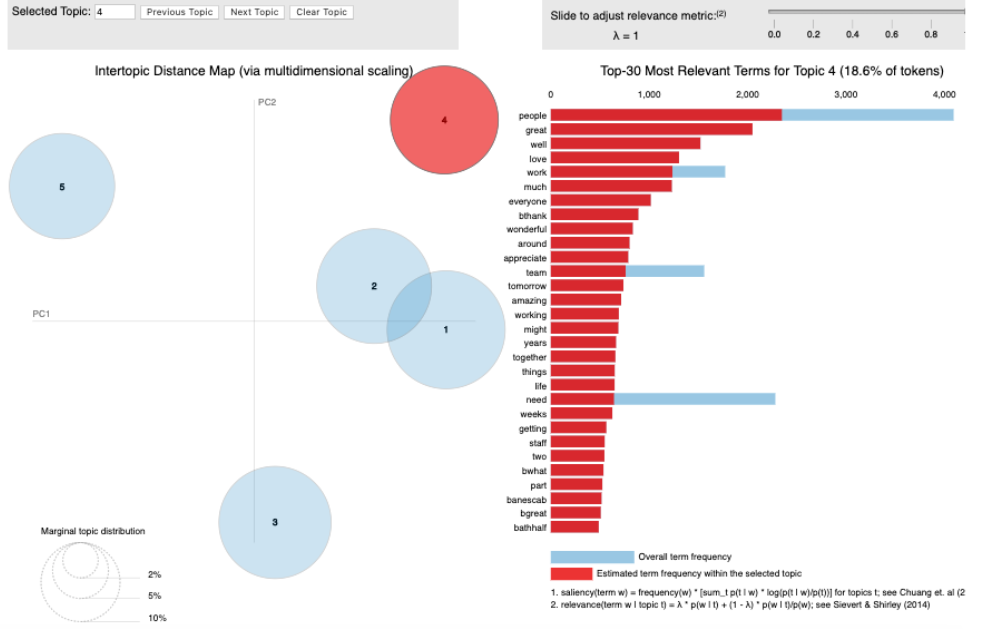

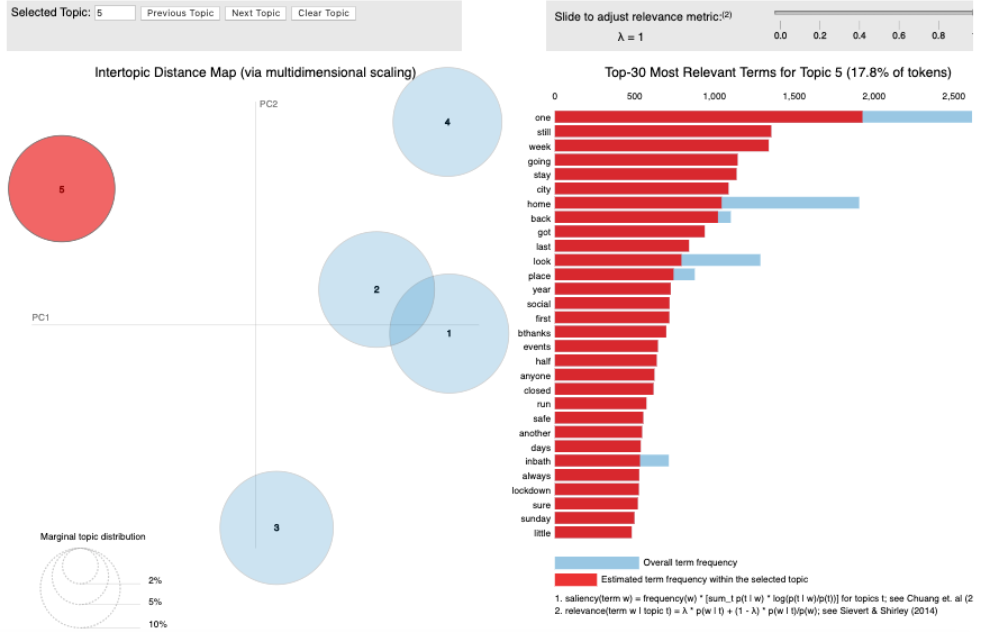

The topics – available as interactive figures here - show the five main topics extracted from the Twitter and Facebook data using a Latent Dirichlet Allocation algorithm. The panels on the left represent the topics, with sizes proportional to their popularity on a two-dimensional inter-topic distance map, while the panels on the right show the top 30 most relevant terms for each topic, their overall term frequency and their term frequency within the topic.

Both platforms are being used to mobilise local communities and support the vulnerable, but in different ways. Overall, topics related to family life under lockdown are much more popular on Facebook, while topics related to the work of local charity organisations are more popular on Twitter, but some of topics are very similar across the two platforms.

Twitter Topic 2 (Fig. 4) and Facebook Topic 1 (Fig. 5) (dealing mainly with general pandemic news and the response of local authorities) are almost identical, while Twitter Topic 1 (Fig. 6) and Facebook Topic 2 (Fig. 7) (which deal with local events) are very similar. These two pairs of topics also cluster close to each other on the map.

At the same time, Facebook topics related to personal experiences and family life during lockdown, which may also include emotionally charged terms such as “anxiety” (Facebook topics 3 – Fig. 8 - and 4 – Fig. 9), do not have a salient correspondent on Twitter.

Instead, Twitter discussions focus more on coordinating and encouraging local causes and avenues for volunteer involvement, and discussing local events such as the Bath Half Marathon (Twitter topic 4, Fig. 10). The twitter data is also notoriously noisier than the Facebook data, demonstrated in Twitter Topic 5 (Fig. 11).

The two topic dimensions resulting from the Facebook data correspond to a personal (left) vs. public-facing (right) dimension, and an individual (up) vs. institutional (down) one, capturing the multitude of ways in which the platform is being used at the local level in the current context.

A closer look at the terms that are most predictive of the personal and individual-level Facebook topics suggests that there are sub-categories within them which can be mapped onto the community crisis engagement debate. Conversations revolve not only around community and volunteer coordination (which is the case on Twitter), but also include individual calls for help and discussions of specific local needs - such as supermarket stocks and queues, interpretation of national and local authority policies and provisions, and details about various informal volunteer arrangements aimed at helping the vulnerable within the community. These types of conversations are less common on Twitter, which in turn acts more as a higher-order aggregator of calls for action.

Overall, the topic analysis shows that there is value in integrating data from multiple social media platforms into local government responses. At the same time, the richest source of data which captures the work of ad-hoc local volunteer communities is Facebook group-level data – most of which is currently not publicly available. The same is true regarding all activity on end-to-end encrypted messaging platforms, such as WhatsApp, meaning a large part of community mobilisation activity happens in isolation, and cannot be studied by researchers in government or academia.

New within-platform tools may be needed to act as a potential link between ad-hoc community groups and local authorities, providing channels through which private community groups - who may want to open up to the public arena, engage more with local authorities, or inform them of the identified community needs and the support that they are providing - could do so.

Network analysis

At the same time, key actors can also behave as intermediaries between online community groups and local authorities. To identify the accounts which are driving online local action we can compute measures of Twitter activity and engagement generation. Based on the overall number of tweets, likes and retweets, the local accounts generating the most public engagement are BANES Council, Visit Bath, Bath Live, Bath Echo and Volunteer BANES. However, a better measure of the key players at the local level would take into account the extent to which the nodes in the local network are connected to each other, as well as the extent to which they help link other nodes within the network.

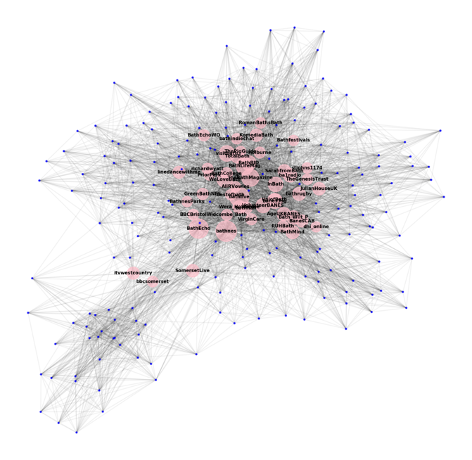

Figure 12 presents the network of co-occurrence between all of the accounts included in the Twitter data. Accounts are considered to be co-occurring if they appear in the same tweet either as a consequence of one of them mentioning or retweeting the other, or as a consequence of both of them being mentioned by another user. Therefore, co-occurrence is a broader measure than co-mentioning or retweet linkage, yielding a rich network structure with over 14,000 links between accounts.

To facilitate visualisation, the network in Figure 12 has been pruned to only include accounts which are well connected (those that form connections with at least 15 other accounts). The users which have the highest degree of centrality have been coloured red and their node sizes are proportional to their centrality.

Apart from the local authority accounts, the local MP and local news and information pages, important linkage nodes in the network over the studied period have also included the accounts of local charities and volunteer organisations. BANES 3SG, Bath Community Volunteer Service, St. John’s Foundation, Julian House UK, Genesis Trust Bath, and Age UK BANES have all been very active and occupy central positions within the network, providing important community linkage points.

Conclusion

Overall, the results show that the pandemic is well reflected in measures of online public engagement. Social media data can be used to provide valuable information about local activities, communities and actors. While local authorities are at the core of both the network of social media key players and the text content they generate, the topics debated in public posts are much broader than those covered by the authorities. At the same time, there are differences in community activity patterns between Facebook and Twitter, suggesting that councils interested in integrating local online support into their work should consider the user engagement across multiple major social media platforms.

An important aspect to note is that the role of local charities and ad-hoc communities goes beyond mobilisation - they also act as linking and coordinating forces between various other actors and online sub-communities. However, scalable integration between the information generated within these ad-hoc communities and the work of local authority structures would require extensive data linkage and analysis, and the development of new digital tools.

While some have noted the lack of online data sharing provisions and standards between national and local government, as well as conflicting digital governance structures within each of the levels, I would like to emphasise another major barrier which could prevent recent developments in online local community engagement from having a lasting legacy – the fact that most of the data on public response, voluntary activity, as well as requests for support at the community level is buried within proprietary and private social media platform pages and groups.

New within-platform tools may be needed to facilitate interaction and voluntary data exchange between these informal online community groups and local authorities. Social media platforms can facilitate the development of such tools by providing increased access to data for research purposes, allowing local authorities to evaluate different solutions. Adopting common data standards and taking advantage of recent innovations in privacy-preserving data sharing would allow them to do so while upholding their high standards for individual privacy.

Are you a decision-maker in government, industry or the third sector responding to the coronavirus crisis? Apply now to our virtual Policy Fellowship Programme for access to University of Bath research and expertise. Learn more.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond