Dr Marsha Wood is a Research Associate at the University of Bath Institute for Policy Research (IPR). Dr Rita Griffiths is a Research Fellow at the IPR and Professor Nick Pearce is the Director of the IPR. This blog post is part of their work on the report ‘A big, vast, grey area’: Exploring the lived experiences of childcare for parents on Universal Credit’ which examines how low-income households on Universal Credit manage childcare costs, as well as their broader experiences of childcare and work conditionality requirements. The research was funded by abrdn Financial Fairness Trust.

Support for childcare in the UK is complex, partial and provision is geographically patchy. There are several streams of support available – some financial, some in-kind, some universal, some means tested – as well as differences across the devolved administrations. There have been recent increases to the free hours of childcare for working parents that have been generally well received. However, there remain issues for parents and providers. For example, the increased free childcare hours often do not address working parents’ needs or cover the full cost of childcare. Low-income parents can therefore find themselves having to reclaim additional childcare costs through Universal Credit, which can be complicated and insufficient.

For low-income families, reclaiming additional childcare costs through UC involves paying the costs upfront and then reclaiming them each month through the online system, after the childcare has been provided. Childcare fees are reimbursed up to 85 per cent of costs, up to a maximum of £1,015 per month for one child and £1,739 per month for two or more children. However, the amount that parents are reimbursed for their childcare is included in their overall Universal Credit award, not separately identified or ring-fenced. It is also means tested. This means that the total Universal Credit payment, including the amount for childcare, can go up or down, depending on household earnings, as the overall award is reduced by the 55 per cent taper rate for earnings above the work allowance (amount some claimants can earn before the taper is applied). There is, therefore, often a big shortfall between the contribution they get, and the full amount of childcare costs they have paid for.

New research into childcare for low-income families on Universal Credit

Drawing on the findings from qualitative interviews with 22 low-income parents in receipt of Universal Credit (UC), our research explored how they manage childcare costs, as well as their broader experiences of childcare and work conditionality requirements. This work is of interest to politicians and policymakers as they develop their strategy for reducing child poverty, in part through increasing economic activity rates and earnings in families and improving early years learning. The Labour Party has also promised to “make work pay” through its New Deal for Working People and increases in the National Minimum Wage. In November 2024 they published the “Get Britain Working” White paper. Ensuring these goals are met for low-income families will depend on the availability of affordable, quality childcare that can meet the diverse needs of all children.

What did the research find?

The parents who took part in our study welcomed the free childcare hours. Yet currently, many low-income families continue to face high childcare costs because they can require more childcare hours than are offered for free; there are variations in support for childcare costs in the devolved nations; providers may charge parents more than the subsidised rates they receive from government, for example, for food; there are earnings thresholds for eligibility for free childcare for working parents; there are no free hours of support for after-school clubs and funded childcare during school holidays is limited.

Although parents on UC can reclaim some of their costs through the UC childcare element if they (and their partner if they are in a couple) are working, most in our sample found the childcare support in UC to be onerous, complicated and inadequate.The most challenging issues were linked to the system of monthly assessment which meant that parents’ reimbursements were not enough to cover the full cost of childcare:

“There wasn’t that much … when it came back from UC.”

Fiona, couple with one child

Monthly assessment also meant that the childcare contribution could vary if childcare costs/earnings and/or household circumstances changed month to month, also making it hard to decipher the accuracy of payment, and to budget.

The requirement to pay childcare costs upfront, in advance, and then wait to be reimbursed for the hours of childcare used within their UC monthly assessment period meant delays in receiving reimbursements and ongoing challenges meeting childcare costs:

“They were just too slow making the payments … I did get it back in the end, but to begin with I was just like basically paying it out of like my budget, and obviously my budget’s not massive to begin with!”

Rachel, lone parent with two children

Delays are especially problematic for parents whose childcare invoices span two UC monthly assessment periods or those who have to pay more than one month’s childcare in advance. Both scenarios meant claimants could wait two months to receive what they are owed:

“So I actually paid that in June, but because it was for like June and July … They didn’t pay it until August or September, so it was a long time.”

Rachel, lone parent with two children

The administrative burden of submitting monthly evidence of fees was additional work for working parents and providers and increased the risk of errors, which could lead to additional delays in payments.

“There were problems with [childcare payments] … there was always some kind of problem. It’s like always. … it’s like a month never went by. And I mean I’m sure you can understand the frustration when I’m working full-time.”

Gina, lone parent with one child

There were also other issues with the UC childcare element included around a general lack of information, limitations of support for upfront costs and poor communication etc which we also explore in the report.

As well, outside of Universal Credit support there were additional childcare challenges such as barriers to accessing two-year old childcare; poor availability of childcare in some areas; providers being unable to meet the needs of children with more complex needs; issues with suitability of after school clubs – especially for older children.

Some parents had to reduce their hours of work; use more expensive providers; or were obliged to use poor quality childcare they were not happy with.

The childcare challenge however was complicated for working parents facing additional conditionality requirements from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to increase their working hours felt that this threatened to undo work-care arrangements which they had struggled hard to achieve. Many jobs available to parents in our sample were not family-friendly in that they did not offer flexible work arrangements or the option to work from home. This made the extra conditionality demands seem especially unfair and hard to achieve for low-income parents.

Parents were facing these childcare challenges alongside other benefit-related barriers to work or increasing their hours, including the loss of entitlement to other means-tested support if their earnings rose above certain thresholds as reported in our recent report and, for couples, the lack of a second-earner work allowance in UC.

What can be done?

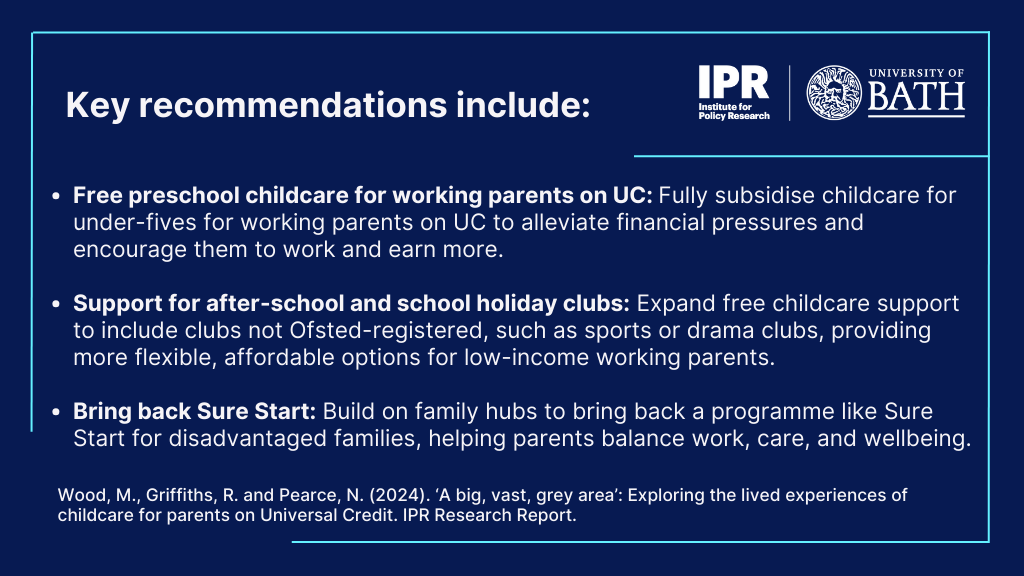

Our main recommendation is to make pre-school childcare for working parents on Universal Credit fully free and pay childcare costs directly to providers across the UK with a one year one year run on of access to free childcare for working parents on UC with pre-school children so that the support would only end if claimants had a nil UC payment for 12 consecutive months.

In the interim (as it may take time to establish paying providers directly) reform of the childcare element of Universal Credit to:

- pay 100 per cent of childcare costs through UC and to ring fence the childcare element so that is not subjected to the earnings taper rate;

- make upfront costs support more widely available to all working parents;

- allow non-working parents or single-earner households who are receiving the free hours for disadvantaged two-year-olds to claim for additional costs such as top up fees or administrative charges through the UC childcare element.

Further recommendations are outlined in our report, including providing some Universal free childcare for all two-year olds, re-establishing the Sure Start programme – building out from the existing Family Hubs network, developing a childcare workforce strategy, improving employment support for parents that recognises the complex and demanding role of being a working parent and reversing the recent extension of conditionality to lone parents and lead carers in couples whose children are aged three - who are now expected to be working or looking for work for 30 hours per week.

The IPR have also published a policy brief highlighting the key findings of the report, with a series of recommendations for policy makers.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond