UK consumers were expected to spend over £700 million on Valentine’s Day gifts last year, with £77 million of that going on jewellery. But how much do we think about where the gold in that ring comes from, or the practices of the company who made it? In this piece, CBOS affiliate member Michael Bloomfield considers how activists and companies use marketing opportunities like Valentine’s Day to get their message out.

Valentine’s Day is a marketer’s dream. Every year, on February 14th, millions flock to the shops looking for romantic gifts for their loved ones. Advertisers play on the emotive nature of the day, running elaborate campaigns to direct these consumer dollars.

So too do activists. In fact, Human Rights Watch has done just that, launching their campaign targeting the jewellery industry.

Human lives matter…

It is time for jewelry companies to address human rights in their supply chains and source responsibly! #BehindTheBling. https://t.co/jiNnh9MZIy pic.twitter.com/brXzdaMTxj— Human Rights Watch (@hrw) February 8, 2018

How activists use marketing

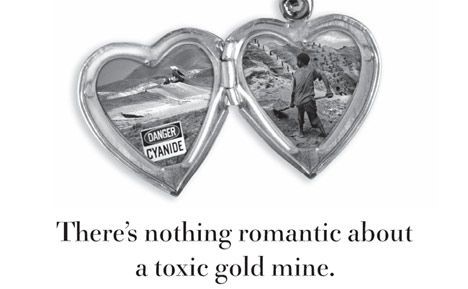

Activists have become adept at using emotive images and associations to trigger responses from their target audience, bringing the underlying issues to life by giving them an emotional context.

Human Rights Watch is not the first group to use this strategy to target the jewellery industry directly. The first such campaign was launched in 2004 by Earthworks and Oxfam America when they teamed up to launch the No Dirty Gold campaign. Just like Human Rights Watch today, they wanted to link luxury jewellery to the social and environmental abuses associated with irresponsible mining practices. And they used powerful images to do so.

Valentine’s Day is an opportune time for these activists to get their message out. In a recent US consumer survey, about 19% of respondents indicated they would purchase jewellery this Valentine’s Day, spending an estimated US $4.7 billion. And if activists can impact these consumers’ purchasing decisions, that gives them a lot of leverage over the companies.

Emotion and activism

Sidney Tarrow has written at length on how emotional framing has become a staple in the activist toolkit. Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink have argued that activists are both ‘principled and strategic actors’, who seek to frame issues is a way that makes them ‘comprehensible to target audiences, to attract attention and encourage action, and to “fit” with favourable institutional venues.’ Tarrow suggests that the most potent strategic framing will ‘identify an injustice, attribute the responsibility for it to others, and propose solutions to it.’ So activists aim to keep the messaging simple, reducing complex connections to relatively straightforward cause and effect relationships.

When it comes to jewellery, activists saw an opportunity to bring attention to the issues facing communities at mine sites around the world. As activists had done in other industries, from fashion (e.g. GAP) to footwear (e.g. NIKE) to forestry (e.g. B&Q) to electronics (e.g. Apple) and agriculture (e.g. Nestle), activists targeted the big, consumer-facing brands and retailers. In doing so, they were trying to achieve two aims: 1) make the link between the brand and the practices they wanted to change, and 2) create supply chain leverage through the brand and its consumers, incentivising their suppliers to change their practices. When it came to changing mining practices, targeting branded jewellers made a lot of sense. So the activists hashed out their plan on the back of a bar napkin.

The consumer response

Shoppers don’t normally think about where the gold in a ring comes from, nor do they think much about the conditions under which it was mined. But they do often distinguish between jewellery brands and those selling them. Tiffany & Co., Cartier, Rolex, and Bulgari are among the most recognisable brands in the world. And one would expect these companies to protect the intangible value embedded in their brands. An attack on gold jewellery could potentially tarnish the entire industry, an industry selling non-essential, emotive products – an industry vulnerable to these shaming tactics. Unsurprisingly, the industry responded.

The corporate response

In my book, Dirty Gold: How Activism Transformed the Jewelry Industry, I investigate in detail how individual companies have responded, why they have done so in different ways, and what impact they have had (and not had) on mining practices. The answers to these questions are important for understanding activist-industry dynamics and how activism can lead to an expanding role for business in global politics.

The key point is that activists have been very good at getting the attention of these big brands and industry has made a concerted effort to reposition themselves relative to campaign accusations. Many signed on to the campaign goals, repositioning themselves to ensure they were not caught on the wrong side of this battle. Others banded together, forming an industry group to protect the reputation of the industry as a whole. Some companies only sell what they consider to be ethical jewellery, usually recycled or ‘fair trade’ gold, and use their company as a platform to advocate for change. And there have been some surprising companies joining them. Even Walmart launched their own line of jewellery to appeal to the responsibly minded, though it has been met with mixed reviews.

What has the impact been?

While the response to these campaigns has been somewhat heartening, there are also plenty of reasons to be skeptical when evaluating the potential of these activist tactics. The question is: can they lead to significant change in practices on the ground? Or is this just spin?

Research by Peter Dauvergne at the University of British Columbia, suggests that these types of campaigns are not particularly effective at changing practice - for example those targeting palm oil users like Nestle and Unilever, have had a very limited impact on palm oil production and the associated deforestation. Similarly, my research on campaigns targeting gold jewellery companies shows that there has not been any measurable impact on the practices of the mining industry.

Part of the reason for this is that the branded jewellery industry has continued to allow substantial leeway for untraceable gold to enter their supply chains. But even more significantly, there remains a large market for gold outside of branded jewellery; the buying power of these jewellers is not as great as it first appears.

But, there can be a normative impact. Part of the role of activists is to draw attention to the externalities of global production and consumption, making links between products, companies, practices, and impacts. Armed with this information, best practices can be defined and irresponsible actors can then be called out.

So there is an important role to be played by both activists and business. This competition between alternative political framings takes place in media and markets year-round, but is particularly visible on days like Valentine’s Day. It has become an opportunity to be seized by marketers and activists alike, an opportunity to reach a larger audience by linking to a particular event. Something which I would never do…

Header image by Myxi under licence CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Respond