On Saturday 18th November, friends and family gathered to remember and give thanks for the life and work of Malcolm McIntosh. Malcolm was a leading writer and thinker in the business and society field, and a Senior Visiting Fellow at the University of Bath. Here, Andrew Crane pays tribute to a much missed friend and colleague.

When I first met Malcolm, he rather alarmed me. Now, when I say I met him, what I really mean is that I bought his book on corporate citizenship – this one – way back in the late 1990s when I was a newly minted PhD student and Malcolm was – well, I will come to that in a minute; Malcolm has never been easy to pigeonhole.

So it would be several years later that I actually got to meet Malcolm in person and later again that we became friends. But, in that first intellectual meeting between me the reader and Malcolm the author I was not sure I actually liked him all that much. I was at the time one of those academics who was – as Malcolm would always disparagingly describe us – rather too preoccupied with obscure scholarly journals that no one ever actually read.

But here was a book that ignored all that academic baggage and captured for the first time the messy and exciting new world of corporate responsibility that was emerging at the time. Like much of Malcolm’s work, it was an exploration of real life practice – of the problems and solutions that were being experimented with by companies at the time – and it was filled with practical, good advice on how to be a more responsible company.

So of course, upstart wannabe intellectual that I was – I hated it. I found it too hopeful and not nearly academic enough for my liking. Where was the criticism? The theory? The intellectual posturing?!

But here it is, fresh off my bookshelf. I still have it some 20 years later. And for many years I actually used it exactly as it was intended – with MBA students and executives who were looking for answers and examples rather than the abstract theory that I had to offer from my own work. Malcolm, along with his co-authors, provided a rich source of inspiration and good ideas.

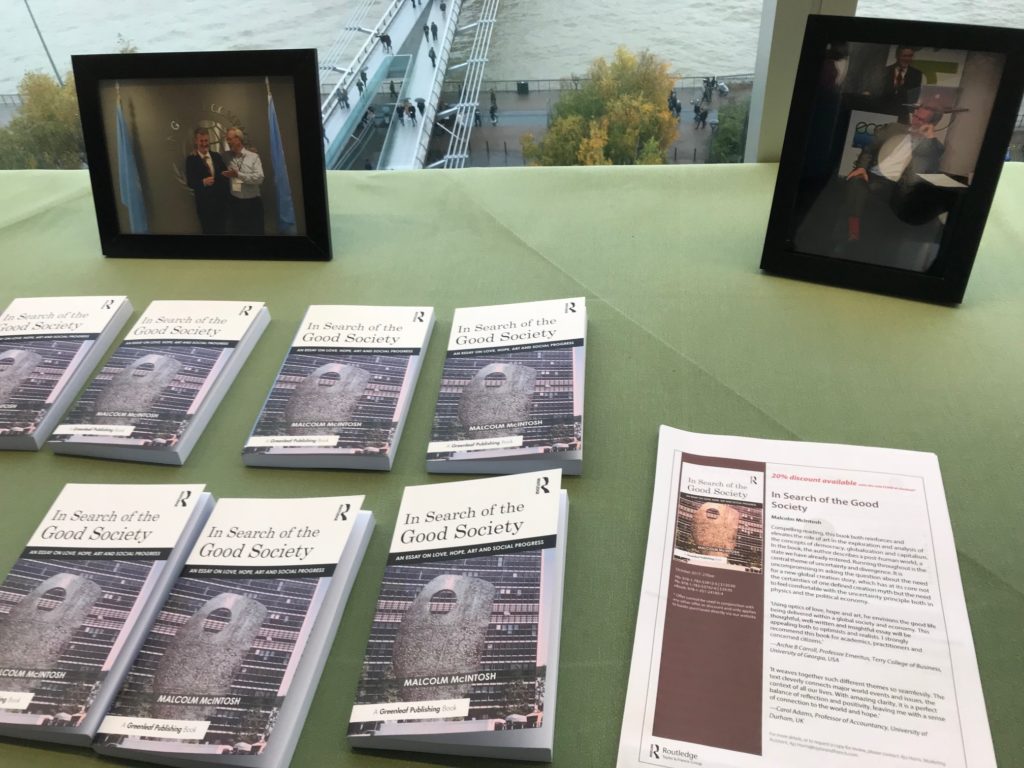

It is something that his work has continued to provide, right up to his latest book, In Search of the Good Society. In it, you can find some of the best health advice you can get, along with insights on art, prosperity and political economy among other things.

It is quite a mix. But as I mentioned, Malcolm has always been rather hard to pin down. Of course, that is probably exactly how he always wanted it to be, too.

When this earlier book came out, he was listed on the jacket as “an independent teacher, writer and consultant”. Now that probably isn’t a bad description for his whole career. Even when he had a formal position – as a Professor, as a Centre Director, as a Special Advisor to the UN – he was just as independent as when he was officially “independent”.

Malcolm, as anyone who knew him soon realized, always had his very own way of doing things. And it never looked too much like everyone else’s way of doing things. He always crossed-boundaries between academia and practice and he had little time for academic disciplines or departments. His latest book, for example, is so wonderfully ambitious in its scope – part travelogue, part art appreciation, part health memoir – that it is almost impossible to categorize.

So University Vice Chancellors would typically either love or hate him, or very often both at the same time. Other academics also didn’t always fully appreciate him, but those that did, turned to him again and again for inspiration and a healthy dose of straight talking. Students naturally gravitated to him because he was so full of new ideas. And practitioners were often drawn to him because he understood them but also challenged them in ways that no one else did.

And I personally found him constantly invigorating. I asked Malcolm many times over the years to give classes to my students, to speak at conferences or examine the theses of my PhD students – and most recently, to join us as a Senior Visiting Fellow at the University of Bath. But I never really knew what I was going to get. That, of course, was a great part of the appeal with Malcolm. He was always so alive with learning and new insights wherever and however he would find them. You could never predict which direction he would head in next.

So, my own relationship with Malcom – our friendship over the 15 years that have passed once we did eventually bump into one another – has always been a source of fun and intellectual stimulation. If I ran into him at a conference whether in London or New York or KL or Cape Town I would naturally seek him out. He would of course have just flown in from somewhere else and have tales to tell aplenty of his travels. He never, ever, seemed to get bored or tired of visiting and learning from other places. And of course, he would have that twinkle in his eye, and that great hearty laugh, as he unwrapped another little nugget of worldly knowledge – or he unravelled another of life’s ironies – or he castigated (but always with such humour) the continued failings of us all to get to grips with the problems of the world.

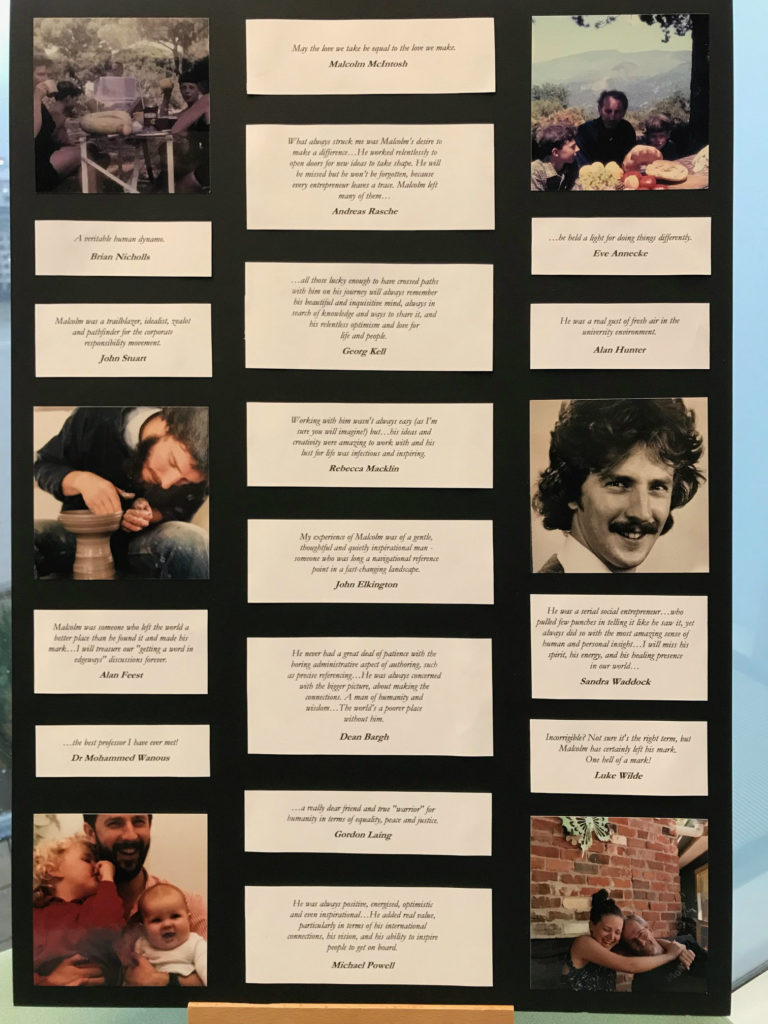

Because, at the heart of it all, Malcolm always, always, always had an unending drive to make the world a better place. His work, really, was a means to an end. He was an unstoppable optimist, ever believing that things could one day be better, and that knowledge, love and understanding were the keys to getting us there. He was constantly planning something new, building institutions, writing books, launching new initiatives, and hacking his own path through the status quo. And it was such a pleasure and an honour to be swept up in all that with him.

So what can I say except that, like many people, I will – I am – missing him terribly and the planet will be a poorer place without him. Right up to the last he was planning the next thing, ready to fire off another book to complete his trilogy. Sadly, it was not to be this time. But he has left us a wonderful repository of knowledge and insight. And in his time here – whether through his work or simply the way he chose to lead his life to the absolute fullest – he helped move us all a little bit closer to the better world, to the good society, that he wanted for all of us.

Responses

Thanks Andy. You captured beautifully what many of us liked and tut-tutted about Malcolm. I had a similar journey from unimpressed to increasingly appreciative, and besides being a fellow pracademic, he was a wise confidante at a critical time in my life.