By Jessica Reyes, Juan Carlos Romero Contreras, James Copestake and Max Nino-Zarazua

Global summits come and go, but do they make any difference? To answer this question it is useful to reflect back on what they set out to do in the light of subsequent events. Ten years ago, on the 28th of September 2011, representatives from eighty low and middle income countries met on the banks of the River Maya in Mexico, and made a series of national commitments to reach out to the 2.5 billion or so people unable or unwilling to use regulated savings, loan, insurance and payments services. These commitments took the form of 837 specific national level targets to promote financial inclusion. Signatories also committed to joint technical cooperation and peer review of progress.

The Maya Declaration on financial inclusion is not without controversy. This was a top-down initiative of finance ministers and central bankers promoted by an organisation - the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) - set up a few years earlier by a private foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Financial inclusion is also one element of the wider trend towards global financialisation, monetizing and integrating human activity into a market-driven global system that incorporates us all, but mostly benefits a rich few. Financial inclusion is a policy agenda of the global establishment: the Maya Declaration following hot on the heels of the 2010 G20 summit in Seoul at which world leaders launched the Universal Financial Access Initiative and the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI).

However, rather than rushing to judgement about the effects of this trend it is worth marking the tenth anniversary of the Maya Declaration by reflecting in more detail on what financial inclusion means, how far and fast it is actually taking place, and with what cost and benefits to whom. While alert to the risks that financial inclusion can facilitate through adverse incorporation into financial markets, it is also important to acknowledge its potential benefits. In 2020, for example, 44 out of 55 of the countries covered by the Global Microscope implemented cash transfers to support vulnerable segments of the population as part of their response to the Covid-19 pandemic. How far did their response to the Seoul Summit and the Maya Declaration improve their ability to do this more effectively?

Definitions and indicators

Definitions of financial inclusion vary. For the World Bank it means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance services that are delivered in a responsible and sustainable way. For the Center for Financial Inclusion it refers to a state in which all people able to use them have access to a full suite of quality financial services, provided at affordable prices, in a convenient manner, and with dignity. In Mexico, the Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores defines it as access to and use of financial services under appropriate regulation that guarantees consumer protection and promotes financial education to improve the financial capacity of all segments of the population. The Zambian Ministry of Finance states that citizens should be able to use appropriate savings, credit, payment, insurance, and investment services to manage risks, plan for the future, and achieve their goals, while firms will be able to access affordable financing to facilitate innovation, firm growth and employment creation.

One obvious group of beneficiaries of financial inclusion are the policy makers, bureaucrats, bankers and academics who make a living from promoting it - and indeed opposing it. Lined up with the AFI and the GPFI are a wide array of development finance institutions, development agencies, and specialists in monitoring financial inclusion. The World Bank maintains the Global Financial Inclusion DataBank, while GPFI produces the G20 financial inclusion indicators, and the Economist Intelligence Unit monitors and ranks 55 countries according to how conducive they are to financial inclusion through annual Global Microscope reports. Clearly, we need a whole dashboard of indicators to monitor all aspects of financial inclusion reflected in the above definitions, particularly to reflect variation in access, usage and quality of services. Table 1 describes just four, illustrated with data for the UK. This serves as a reminder that very high rates of access to financial services are normal in high-income countries, with most people taking them for granted in much the same way as they do access to drinking water, electricity or education.

Table 1: Four indicators of financial inclusion

| Indicator | Description | Data for the UK | ||

| 2011 | 2014 | 2017 | ||

| Adults with a bank account (%) | Percentage of adults (aged 15+) who report having an account, by themselves or together with someone else, with a formal financial institution or a mobile money provider. |

97.2 |

98.9 |

96.4 |

| Women with a bank account (%) | Percentage of women (aged 15+) who report having an account, by themselves or together with someone else, with a formal financial institution or a mobile money provider. |

97.7 |

98.7 |

96.1 |

| Adults who made or received digital payments in the past year (%) | Percentage of adults using a transaction account with a bank or other formal financial institution or mobile money provider to make or receive a digital financial payment. This includes use the internet, a phone, or a debit/credit card to pay bills, make purchases online, send or receive money from a bank account, or receive payment from government. |

n/a |

97.0 |

95.5 |

| Adults who received wages or government transfers into an account (%) | Adults who received wages or government transfers into an account with a bank or other formal financial institution or mobile money provider.

|

n/a |

63.8 |

75.5 |

Promoting financial inclusion in Mexico, Peru, Malawi and Zambia

To delve deeper into changes in financial inclusion we contrast two middle-income countries from Latin America (Mexico and Peru) with two low-income countries from Africa (Malawi and Zambia). Each country committed to ten specific financial inclusion targets under the Maya declaration (illustrated in Table 2). They included setting physical targets for national outreach, facilitating development of digital financial services, promotion of financial literacy through the school system, measures to strengthen consumer protection, and investment in systems for monitoring financial inclusion trends.

Table 2. Illustrative Maya Declaration targets for Mexico, Peru, Zambia and Malawi

| Theme | Mexico | Peru | Zambia | Malawi |

| Setting overarching outreach goals | At least 50% of the adult population have a formal savings account by 2024. | Banco de la Nación will have a bank branch with digital connectivity in every district by 2022. | Increase financial inclusion from 37.3% to at least 50% by 2016. | Achieve the Bank of Malawi 2016-19 plan by achieving a 16% point increase in financial inclusion. |

| Digital financial services | To increase monthly debit/credit transactions via points of sale to 35 per adult by 2021. | Open 1 million basic digital savings accounts linked to adults’ National Identity Cards (DNI) by 2022. | To extend agency banking via mobile money agents to all districts by 2017. | To extend agency banking via mobile money agents to all districts by 2017. |

| Financial Literacy & Financial Education | Incorporate financial education content into the elementary school curricula by 2018. | Develop financial education programs for children and youth within the formal education system by 2013. | Develop and implement a national financial education strategy through integration in the school curriculum by 2012. | Develop a national financial literacy and consumer education strategy by June 2012. |

| Financial inclusion data | Design a panel survey to assess the impact of financial inclusion in Mexico by 2018. | Develop a demand side national survey of financial inclusion and financial literacy by 2013. | Integrate gender disaggregated monitoring of financial and digital inclusion by 2017. | Develop a strategy for ensuring more transparent pricing of financial services by 2011. |

Outcomes

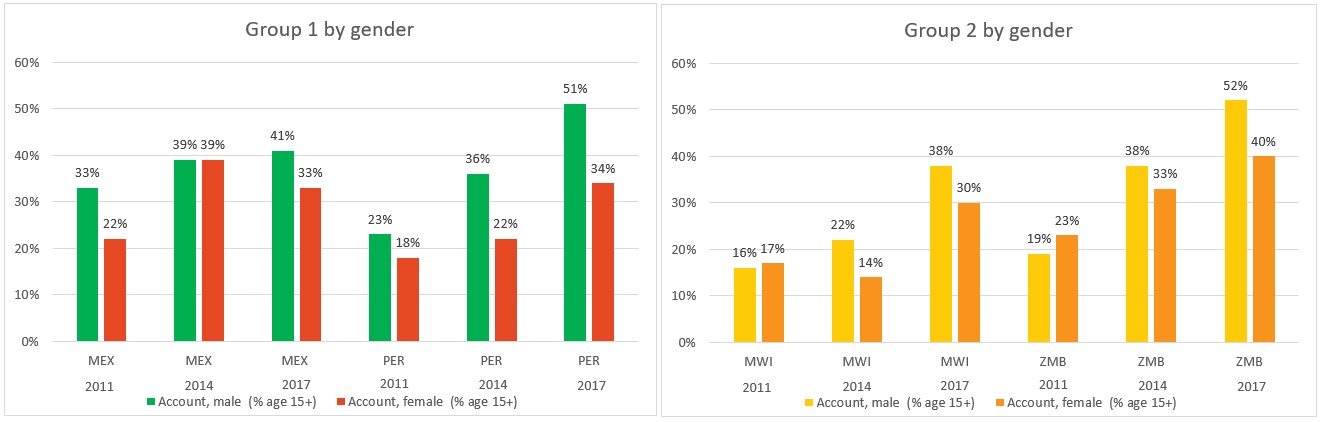

So, what progress has been made? Chart 1 shows changes in the number of adults with a bank account in the four countries between 2011 and 2017, based on the Global Findex database. The general trend over the six years is upward for both men and women, with the one exception being Mexico, where financial outreach faltered after 2014, particularly for women[1]. Ownership of bank accounts by women in 2017 lagged behind that for men, particularly in Peru. In both Zambia and Malawi more women had a bank account in 2011 than men, but by 2017 the gap had shifted the other way and was widening.

Chart 1: Adults with a bank account, by gender, for selected countries, 2011-2017

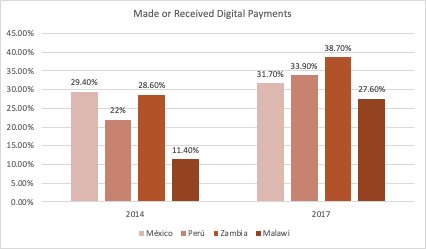

Chart 2 reports on those who made or received a digital payment in each country, revealing sharp increases in Peru, Malawi and Zambia, but little change in Mexico. But the rates shown are still far below the 95% rate in the UK. Of course, a lot has happened in the four years since 2017. For example, the emergence and increasing growth of the so called FinTech (financial technology) and digital financial services are shifting financial inclusion towards large-scale data-driven and digital services and products with potential wider outreach. Also, it is likely that use of digital payments continued to grow ahead of the Covid-19 pandemic, and then accelerated in response to it. This highlights a second positive effect of financial inclusion on capability to manage the pandemic i.e. not only did it facilitate government transfers, it also facilitated more payments and transactions without physical contact.

Chart 2: Adults with making or receiving digital payments in selected countries, 2014 and 2017

Conclusions

The interaction between the global push for greater financial inclusion, new opportunities and challenges with FinTech and the Covid-19 pandemic is highly complex. In addition to facilitating social assistance and distancing, better access to appropriate financial services can help people save ahead of emergencies and smoothen their consumption (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2021). However, financial inclusion may also be associated with higher levels of indebtedness that aggravate shocks and leave borrowers worse off. The rapid growth in commercial finance for schools and school fees, for example, sits awkwardly with the effect of protracted school closures due to the pandemic (e.g. see EduFinance, 2021). Meanwhile, the spread of digital financial services is opening up new threats as well as opportunities, demanding new financial capabilities, regulations and forms of consumer protection. This blog has merely scratched the surface of the complex global, national and local system changes associated with financial inclusion, and leaves many unanswered questions about its effects. But it suggests that research needs to engage with the granularity of financial inclusion and its welfare effects, rather than fuel sweeping endorsements or criticisms.

Notes

[1] According to the Mexico National Council for Financial Inclusion, the number of women with bank accounts increased 17% from 2014 to 2017, suggesting a data discrepancy between the Global FinDex and Mexican official data (see https://www.pnif.mx/documentos/).

Respond