By Yixian Sun

Chinese President Xi Jinping recently announced at the UN General Assembly that China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”. Chinese banks have already swung into gear. Three days after Xi’s speech, the Bank of China declared it would no longer provide financing for new coal mining and power projects outside China from the last quarter of 2021. Xi’s statement is expected to affect at least 54 gigawatts of proposed China-backed coal plants that are not yet under construction. Shelving these would save CO₂ emissions equivalent to three months of global emissions.

This pledge from the world’s largest public financier of overseas coal plants could usher in a new era of low-carbon development. But that depends on what happens in the countries where China had funnelled money into coal power. Many of these places urgently need new energy infrastructure. Will China’s investments here be redirected to renewable energy – or simply disappear?

Chinese support for renewables abroad

One positive sign came in the same speech to the UN, when Xi indicated that “China will step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low-carbon energy”. China’s overseas energy investments grew as part of the belt and road initiative. Launched in 2013, Xi’s signature foreign-policy effort increased China’s cooperation with the rest of the world through infrastructure development, unimpeded trade, financial integration and policy coordination. China has continued to provide finance for the belt and road initiative during the pandemic, and investment in renewables made up most (57%) of the country’s financial support for overseas energy projects in 2020 – up from 38% in 2019.

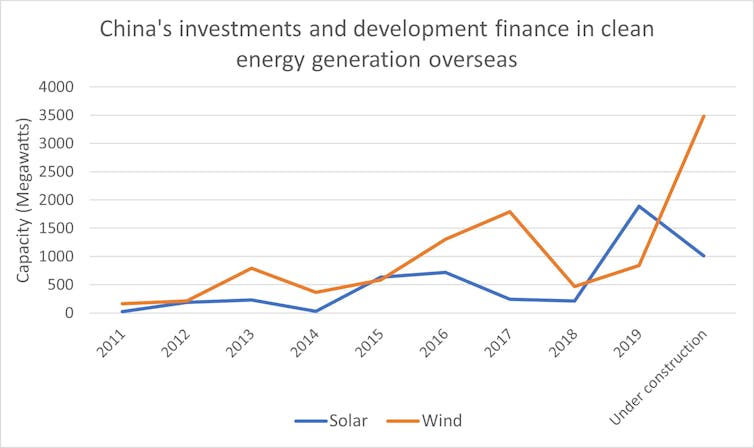

Beijing has supported wind and solar projects in more than 20 developing countries since 2013, including Ethiopia and Kenya. And Chinese banks and companies have also expanded their overseas investments in renewable energy over the last decade.

While the trends are positive, challenges remain. China’s overseas investment policy remains guided by the non-interference principle. This means that Beijing is supposed to let host countries determine the type of energy projects, and only requires Chinese firms to comply with host-country regulations. Research shows that China’s finance for coal in Asia was largely driven by demand in recipient countries. This is because the domestic policies of these countries prioritised improving energy access over reducing emissions, and coal was a cheap and proven source. Inadequate grid infrastructure and politicians sceptical of renewable energy in countries receiving Chinese investment have also hampered development. In Indonesia, business leaders and politicians formed pro-coal lobby groups to influence the design of China-backed projects.

China’s new pledge tells prospective recipient countries that coal finance is no longer an option. China must now promote its offer of investment in renewables. Drawing on its domestic experiences, Beijing should provide subsidies or tax cuts to companies willing to build renewable energy projects outside China. Chinese energy developers are often wary of investment risks in developing countries due to their unfamiliarity with local politics. The Chinese government can help by increasing coordination between Chinese companies and local governments, businesses, and communities in host countries.

Over the past decade, China has supported many developing countries to increase their energy generating capacity with financing, affordable technology and quick project delivery. China has taken the first step to stop funding coal. It’s now time to adopt policies that support the overseas activities of its renewable energy developers.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Responses

https://sora168.com