Flipping is a useful case study to use to consider how we may teach the same course, content, and outcomes in a different way. It won’t work for everything, but it raises some useful questions for thinking about your course. This is an introductory briefing about the idea and some considerations for both staff and students.

What is flipping?

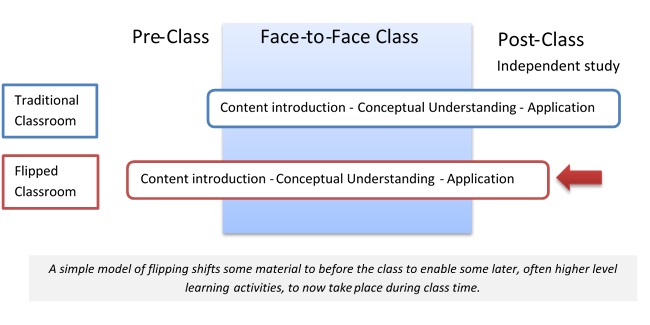

Flipping, or inverting the classroom, is a teaching methodology that swaps some of the material and activities from the face-to-face classroom session (usually lectures), with work previously done outside the classroom e.g. independent study. The primary motivation comes from asking the question

“what is the most effective use of the face-to-face classroom time with the lecturer?”

Often in a traditional lecture, class time is in part used to introduce basic definitions and content, and the students are largely passive. In less traditional lectures, lecturers may use a variety of active learning, engagement and interactivity tools, but are faced with balancing the delivery of essential content. However, the (often more difficult) higher level work of trying to understand the concepts and practise applying them may well be done in independent study, without the direct support and feedback from the teacher or peers. Where would we prefer the face-to-face time and the resource of the teacher/lecturer to be used?

How it works

Flipping can be done in a wide variety of ways, with the ‘flipped’ material delivered in a range of formats (e.g. notes, videos). The lecturer will provide instructions for material that must be viewed before the class at a time, place and pace of the student’s choosing. This thus involves some pre-session work from students for sessions (such as lectures) which may not have had this before. However, some of the work that the student would have had to do after the session now takes place in class. The sessions can now also be more interactive and time is freed to make use of further active learning and teaching techniques, which have been shown to be more effective. The aim is for this to be done in such a way that it is also quicker and more supported than the same study in independent learning time. This doesn’t mean that all of a lecture is ‘flipped’ beforehand, nor that no independent study is needed afterwards, but it is shifting some of these areas so that each stage is used more effectively.

Key advantages/aims

- Basic introductory material and content can be delivered outside of class and thus free up time in class to be used more effectively.

- The flipped content can be studied/re-viewed at a time, place and pace more convenient for the student. This can also help with some diversity in students’ background, knowledge, and learning needs.

- Students can potentially flag up any questions/difficulties with material before the session enabling the lecturer to prepare more detailed targeted support (this is known as Just in Time teaching). Usually, such problems only come to light during or after the lecture, when the lecturer cannot as easily respond or adapt and prepare.

- Face-to-face class time is freed up for more active, and less passive, learning approaches. There is less ‘lecturing’ at students, particularly on relatively simple introductory topics.

- Face-to-face class time can concentrate on higher level conceptual understanding, on applications, more examples, and/or in responding to students’ questions/difficulties.

- Whilst overall students should not end up spending more time working outside of class, it is at a different time. This effectively forces some studying to be done earlier that might be left until later e.g. revision periods. Students often find there is quite a bit left to understand (when they try to now apply the knowledge) or learn for the first time, but now without the direct support of the course. Similarly students can fall behind or leave a topic before it is properly understood because the course has already moved on.

Initial considerations for staff

- What is the best use of the limited contact time with you? This is the key question. What is the best use of you (a major resource) and the advantage you bring to a session? Examples include motivation, inspiration, interactivity, feedback, and your thought processes and approach being demonstrated live.

- You do not need to flip an entire session: there is a limit to what the students can/will do outside of class. The new ‘lecture’ can be a mix and many flipped sessions flip only a portion of the content. Similarly, not all sessions need to be flipped, but overall some coherence and structure is useful.

- Consider carefully not just the amount but the cognitive/conceptual level of the material to be flipped. If this is too high, it may not be suitable that the first introduction to it is ‘self-studied’. However, there is usually a lot of content that could just as easily be read or watched.

- Creating this content (or finding suitable content) can take a lot of time, so there is an upfront investment. When successful, those flipping have found this pays off, as the material is updated/reused, but time is also saved later in the course.

- Will the students complete the pre-session work? You may be familiar with pre-reading for e.g. seminars, and some study techniques can be carried over to this method (the difference however is that this might be the first introduction to concepts). Can you still engage with the session properly without doing the work? Tasks need to be at a high enough level for this to not be the case. Remember, part of the purpose is to have time for higher level, more challenging, activities

- The expectations of the students: This needs to be carefully managed. If they are expecting a ‘lecture’ and to be ‘taught’ for that session, they may not be ready to actually work in them. Similarly, this is a different way of working. For both of the above points, it may be useful to explain your rationale (a student version of this briefing is available to adapt should that help) to help avoid the problems that could occur for satisfaction/engagement with the course.

Advice for students

The following are examples of advice that could be given to students when introducing a flipped approach in the classroom:

You may be familiar with pre-reading for e.g. seminars, and some study techniques can be carried over to this method (the difference however is that this might be the first introduction to the content).

- Schedule time in your diary to do the pre-session work, preferably before the actual day itself. This is a key part of flipping – it requires organisation from the student at a time when all courses are busy, but without covering the basics pre-session, the attempt to concentrate on higher level learning in class will be wasted or not possible. If you do not schedule time it is easy for it to be left too late or not completed. However, you now have more flexibility as to when/where/how you study this material.

- Note any questions you have based on the ‘flipped’ content or areas you are unsure about. The lecturer may explain these in class (e.g. spending the time now on more difficult parts), provide mini-tests to check knowledge, or provide methods for these questions to be asked and explanations provided. Feed back to the lecturer, so they know which areas students are less confident on (something that is difficult to know in a standard lecture).

- Be ready for a more active learning approach in the session – you may need to ensure you have your notes from the flipped content and potentially other equipment or resources on hand to effectively apply the knowledge in the session that you may not have needed in a standard lecture. You may even be in a different location (e.g. moved from a lecture theatre to a computer or group work room).

- Provide feedback to your lecturer. Lecturers engaged in flipped approaches are actively putting in time and effort, aiming to provide a more effective face-to-face class. This involves a lot of choices as to what to flip and what to do in the class. Providing feedback helps them to evaluate those choices or to flexibly adapt plans and future sessions. Feedback on difficult areas, questions asked, and mini-test results similarly help the lecturer to be more responsive to students’ actual learning and level

Next Steps

The above is an initial selection of major considerations, but more detailed advice is available, along with case studies from Bath, consultation and support for academics: Contact Dr Giles Martin (g.d.r.martin@bath.ac.uk).

Other flipping related resources and case studies on the Exchange blog can be found under the flipping tag and via the University's Flipping Project Website.