Dr Aurelien Mondon, Senior Lecturer, Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies

The campaign for the UK referendum appears to have induced the French to confront their own pessimistic view of the Union and its future. A recent poll conducted by Eichhorn et al. in six countries suggested that French respondents were the least keen to see their British counterpart remain in the EU, with 44% declaring that the UK should leave. This was in stark contrast with other countries: Brexit supporters were 27% in Germany, 20% in Poland, 19% in Spain, 21% in Ireland and 33% in Sweden.

Of course, such dissonant results may be partly attributable to the UK’s reputation as an ‘awkward partner’ within the EU, something which has led to multiple feuds between UK and French leaders. However, one cannot ignore that the campaign takes place in a unique environment in France, at a time when one of the leading engines of the European construction is faltering, with warning signs flashing from all directions, and no one seemingly willing to put in the necessary work to get it going again. Beyond the UK’s fate, the same poll highlighted that 53% of French respondents wished for their country to ‘hold a referendum on its EU membership’ and only 45% declared they would vote for France to remain in the Union; 33% would vote for it to leave. Again, these numbers are in stark contrast with Germany in particular, leading the Le Monde correspondent to conclude that ‘while the French profess a relative indifference with regard to the Brexit, they appear as the most eurosceptically worked up country, behind the UK’.

As has been the case on the other side of the Channel, the debate in France about the possibility that the UK leaves the EU after the referendum in June has been predominantly negative. The political climate has meant that, even in a traditionally pro-EU country, the arguments made for a ‘Bremain’ appear based on a pessimistic approach rather than the enthusiasm which had historically been core to the European project: If you stay it won’t be great, but if you leave it will be worse.

In France, the debate is also taking place in a particularly hostile environment for ‘internationalist’ ideals. The European elections were commonly characterised as an ‘earthquake’, with the Front National winning the contest with almost 25% of the vote. For left-wing newspaper Libération, France had sent a clear signal to Europe (see image 1).

Image 1: Libération front page, 26 May 2014

Even though the Front National (and UKIP) failed to appeal to more than 1 out of 10 voters in a particularly advantageous setting, their victories created hype around their message and legitimised their negative account of the situation as it was picked up by the media and politicians. In turn, a stronger focus on issues of immigration and terrorism (particularly in the wake of the horrific attacks in France in 2015, often linked to the refugee ‘crisis’) have skewed the campaign away from the real challenges facing Europe and the attention of the public away from their own concerns. To put it simply, and borrowing from agenda-setting theory, the media and politicians ‘may not be successful in telling people what to think, but they are stunningly successful in telling their audiences what to think about’ (McCombs 2014). As a result, the debate has moved away from socio-economic issues (unemployment, cost of living, healthcare etc.) to nationalistic and pseudo-cultural issues (immigration, terrorism, Islam).

Immigration and public opinion – the chicken or the egg?

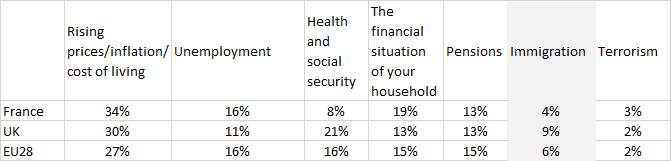

This negative and skewed media coverage of the EU debate is reflected in the way people (mis)perceive their broader community and the issues these imagined and fantasised communities face. A simple, and by no means exhaustive experiment, can be conducted using two questions from the Eurobarometer survey. The first requires respondents to provide what they think are ‘the two most important issues facing (their country) at the moment’.[1] As Table 1 suggests, immigration does seem like a genuine concern across the EU, and in the UK in particular where it is noted as the most important issue. In France, however, a year after the Front National’s victory in the European elections, immigration is considerably lower, showing already a discrepancy between the results and subsequent coverage and public opinion.

Table 1: Question: What do you think are the two most important issues facing (YOUR COUNTRY) at the moment? (Top 5 EU answers with immigration and terrorism). (Source: Eurobarometer, Spring 2015. Source: Eurobarometer, Spring 2015).

However, a starker picture emerges when French, British and European respondents are asked what they think affects them personally. When European citizens consider their daily struggle, immigration and terrorism remain low on ‘the most important issues’ they face ‘personally’ (despite the poll taking place after the January Paris attacks). ‘The most important issues’ the French, British and Europeans are facing are those which have seemed conspicuously absent in the public debate about the future of the EU (see table 2).

Table 2: Question: And personally, what are the two most important issues you are facing at the moment? (Top 5 European answers with immigration and terrorism). (Source: Eurobarometer, Spring 2015).

This is not to say that the results from the Eurobarometer should be taken as real representation of public opinion personally or nationally. Yet this demonstrates that what is often argued to be a pressing popular demand or concern may in fact be motivated by the process through which perceptions and misperceptions are made available via the media and politicians. To put it simply: are we worried about immigration, or do we think about immigration as an issue because we are constantly told we should?

The rise of the Front National or a growing distrust towards the mainstream?

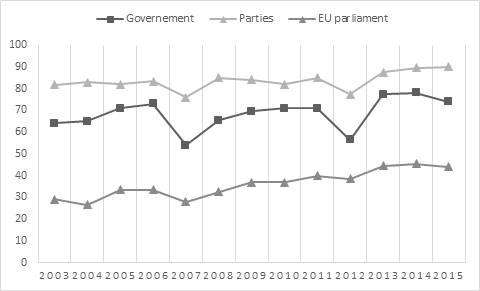

Therefore, the Front National’s victory in the European elections in 2014 may not have meant unconditional support for the party and its Europhobia: more than a ‘Eurosceptic earthquake’, the election results confirmed that the vast majority of French voters saw little interest in voting at all (57% abstained). This is hardly surprising considering the oft-denounced democratic deficit in EU institutions and the lack of knowledge about its inner workings. Yet it would be a mistake to read the results of these elections outside of the socio-political context in which they took place. These elections took place in a deeply distrustful environment, with the government’s approval ratings at a record low. However, it would be simplistic to blame the rise of Euroscepticism and even Europhobia in France on François Hollande’s presidency. As figure 1 below shows, distrust of parties and government has run rampant in France throughout the early twenty first century. For the government, the level of distrust has never fallen below 54%, while for political parties in general, the biggest dip was in 2007, with 76% of respondents declaring they tend not to trust political parties (including the Front National). In 2014, it was almost nine out of ten French respondents who declared they did not trust their parties.

The European parliament, on the other hand, generates a lower ‘distrust’ rate than the French government and political parties. In fact, before 2013, more respondents to the Eurobarometer declared trusting the European parliament than distrusting it.

Figure 1: level of distrust in ‘government’ (question: ‘I would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?’ Answer: ‘Do not trust’); level of distrust in ‘political parties’ (question : ‘I would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?’ Answer: ‘Do not trust’); and level of distrust in ‘European parliament’ (question: ‘please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?’. For each year when more than one poll was taken, the average is represented. (source: Eurobarometer)

Another Europe is possible

Gauging trust and distrust in politics is a tricky business – after all, someone distrusted may be competent – but the levels of negativity felt by the French with regard to their own institutions may inform us about the reasons behind the growing Euroscepticism in France.

While the mediatised picture may seem bleak, 61% of the French respondents to the 2015 Eurobarometer declared that felt ‘they are citizens of the EU’. Contrary to their British counterparts, who tend to be more negative on most counts with regard to the EU, its benefits and future, it could well be that what the French are looking for is not a return to some nationalistic and chauvinistic project, but rather the creation of a different kind of Europe, based on a progressive outlook. A focus on issues such as TTIP, the future of our welfare systems and work rights legislation would appear more in line with Europeans’ concerns, but also provide a much sounder basis to discuss broader international issues such as our foreign policy and the current influx of refugees. If this is to be taken as a serious hypothesis, then what is mostly described as the rise of an anti-Europe sentiment, could and should in fact be channelled into a more optimistic and productive discussion, something which unfortunately has been conspicuously absent from the elite debate on the future of Europe.

This blog post is part of a new IPR Series – all related to the BREXIT debate and the EU Referendum. This collection of commissioned blog posts will be published as an IPR Policy Brief in May 2016. Sign up to the IPR blog to get the latest blog posts, or to our mailing list to receive invitations to our events and copies of our Policy Briefs.

[1] Respondents could provide a maximum of two answers from the following list: The financial situation of your household; Rising prices\ inflation; Other (Spontaneous); None (Spontaneous); Don’t know; Crime; The economic situation in (OUR COUNTRY); Taxation; Unemployment; Terrorism; Housing; Immigration; Health and social security; The education system; The environment, climate and energy issues; Pensions; Energy; Defence/ Foreign affairs; Living conditions; Working conditions.

Responses