An important factor in Hilary Clinton’s victory in the Democrats’ Presidential nomination race was the support she attracted from middle-aged and older women. As is well known, millennials broke for Bernie Sanders, but Clinton won the support of women in their thirties and upwards.

There are plenty of reasons for this, but one has to do with Clinton’s consistent advocacy of stronger parental leave and family-friendly employment rights, and her commitment to expand early-years education. US women who have children are hit by one of the least-supportive welfare states and employment policy frameworks for parents in the developed world. It's no better for men who become parents either.

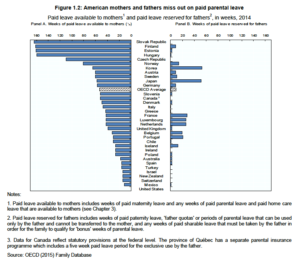

As the figure below shows, the USA is at the very bottom of the table of OECD countries in the provision of paid parental leave available to mothers and fathers. There are no nationwide rights to paid maternity, paternity or parental leave.

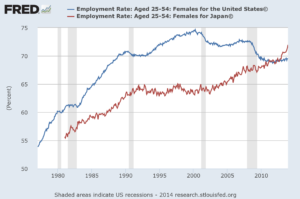

Partly as a consequence of its failure to institute paid parental leave, flexible working and decent childcare policies, the USA has seen a decline in the female employment rate in recent years. Here’s how the US and Japan have fared over the last few decades:

Clinton’s main policy commitment is to pay 12 weeks at two-thirds of wage replacement for family or sick leave (for the care of newborn or sick children, the care of spouses and relatives, or recovery from serious illness). This will be paid for by taxes on the wealthy, rather than a system of national insurance or payroll taxation. This policy has already been introduced in New York state (some other states, like California, also pay leave, but only for six weeks). If OECD evidence is anything to go by, the policy should start to lift the female employment rate by making it easier for women to combine work and motherhood or family care (although there are, of course, other determinants of the decline in female employment in the USA).

The policy simply brings the USA up to the starting gate, however. Most other OECD countries have much more extensive forms of leave. As ever, the Nordic countries stand out as having the best provision for parents and children in their early years, combining generous paid parental leave with universal childcare and family-friendly employment. This ensures high female employment rates, and extensive enrolment in early learning for toddlers – a dual carer-worker model that ensures child poverty is very low, and egalitarian outcomes for children are high.

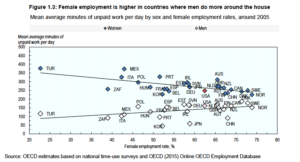

The leading-edge Nordic countries – chiefly Iceland, Norway and Sweden – also reserve a portion of paid leave for fathers (so-called “Daddy Leave”). This ensures greater gender equality in leave take-up, which in turn has knock-on consequences for equality in caring and household labour tasks. Look at the clustering of the Nordic countries at the right hand end of this graph, again from the OECD:

Interestingly, a number of other countries have followed the Nordic lead. On average, men’s use of parental leave is rising – in Finland the male share doubled between 2006 and 2013, and in Belgium grew by ten percentage points over roughly the same period. Germany brought in extensive reforms in 2007 that improved pay for leave periods and gave bonus leave to families where fathers took leave. Elsewhere in Europe, policy has changed but practice has not: French and Austrian men haven’t increased their leave rates. The UK has become slightly more generous to fathers, allowing women to transfer some of their maternity leave to men – but take-up, unsurprisingly, is low. The gender pay gap, lack of reserved “Daddy Leave” and low flat rates of statutory pay all militate against it.

Interestingly, some of the most extensive leave provision for fathers is now found in South East Asia, where countries like Korea and Japan have sought to boost female employment rates – to cope with demographic pressures and the loss of productive talent – by expanding leave entitlements for both men and women. In the first decade of the 21st Century, Korea took a “social investment state” turn and gave parents extensive new leave rights, alongside improved childcare: fathers are entitled to 53 weeks of paid paternity and parental leave that can only be taken by them. But socially conservative attitudes, particularly amongst employers, have held men back from taking up their rights; public policy has not yet fostered widespread cultural and structural change, as it has in the Nordic countries.

Yet overall, austerity in the EU and fiscal constraints elsewhere do not appear to have impeded the advance of public investment in childcare and parental leave entitlements. Spending cuts have been made in the UK and elsewhere, but the trajectory is still broadly upwards along the continuum towards the Nordic model in advanced capitalist economies. The pre-crash social investment state paradigm appears – in this area of policy, if not in others – to have retained its traction. But to really achieve its gender equality goals, it has to provide for men and women, mothers and fathers – asking employers, as well as the state, to play their part. To be with her, you need to be for him.

Sources:

You gave tremendous positive points there. I did a search on the topic and found most peoples will agree with your blog.