Marcelle McManus is a Professor of Energy and Environmental Engineering in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bath.

Until last month the UK’s capacity market was the flagship mechanism for helping the UK meet its Climate Change reduction targets whilst maintaining a secure electricity supply. On 15 November however, the European Union Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled the mechanism unlawful. Despite the huge implications of this decision, it was easily missed – buried under Theresa May’s reveal of her Brexit deal.

What is the Capacity Market and why do we need it?

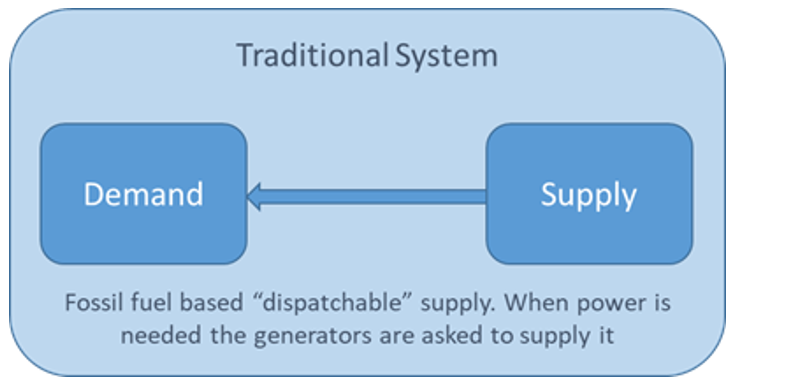

Until relatively recently our electricity was provided predominantly by fossil based fuels. Fossil fuels are known as “dispatachable”, as the feedstock can be stored and the power produced when required (Figure 1). However, the increasing penetration of renewables into our system has meant that we needed to re-think the system.

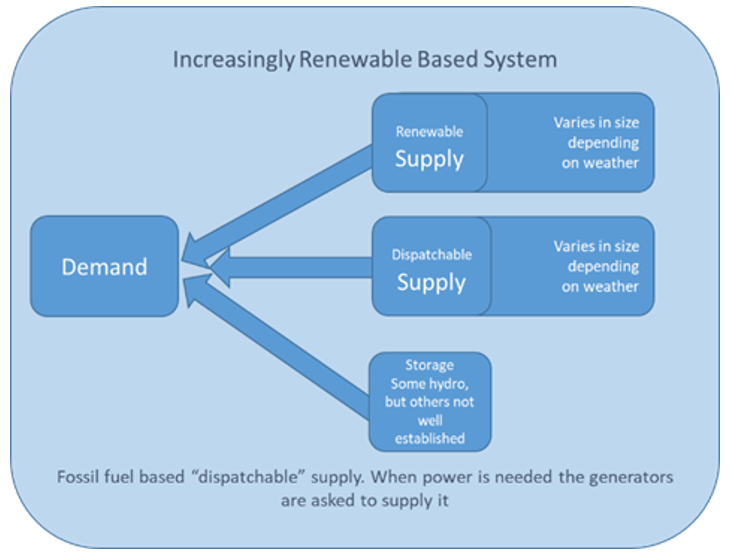

In general (with some exceptions, such as bioenergy), renewable technologies are known as “supply led” or non-dispatchable. This means that instead of the power being produced when the consumer demands, it is produced when the weather dictates. For a small penetration of renewable technology this is easily dealt with by the grid, but for a larger penetration a system has to be put in place that can enable the continuous supply of power (a secure supply) with an increasingly varying supply source.

There are several ways in which we can deal with this. One option is to change demand (demand side management), the other is to increase the use of storage (which still needs further development). Another option is to incentivise dispatchable sources to be online, ready to pick up any drop in supply (Figure 2).

The Capacity Market (CM) was initiated to help provide the back-up generation of power and demand side response to help balance the network at times of stress, caused by periods of high demand and low renewable supply. Participants in the CM are paid per Mega Watt (MW) for the capacity they offer – and this needs to be available when they are called upon by the National Grid as agreed in their contract.

How did the Capacity Market work?

In order to offset the risk of investing in less predictable supply, fixed monthly payments were made to generators, and to those willing to reduce demand when required. Participants could bid for contracts, first agreed at the end of 2014. Their requirement to start providing capacity started last winter.

They are required to notify providers and deliver a “Capacity Market Warning”. This is issued by the National Grid, and outlines the start time of the warning (usually four hours before the required delivery time), the circumstances of the warning, the settlement period and the percentage of their total obligation the provider will be required to deliver. Significant funding was set aside for the CM – up to £2.6billion per year - and it was deemed the most appropriate mechanism for helping meet demand in an increasingly supply led system back in 2012.

What happened?

Tempus Energy took a case to the European Court of Justice. They felt that the CM favoured the use of fossil fuels rather than the other mechanisms in place such as flexibility, demand side response, and management and storage. They were concerned that the European Commission had not fully investigated the CM when it was first introduced in 2014.

Tempus, and other Demand Side Management companies, argued that the CM made it harder for them to compete with the well-established fossil fuel based power generators. Under EU State Aid rules, member states are obliged to consider alternative ways of meeting market demand for power before subsidising polluting generators. They also require any capacity-boosting measures to be designed in a way that provides "adequate incentives" for operators of new, cleaner technologies.

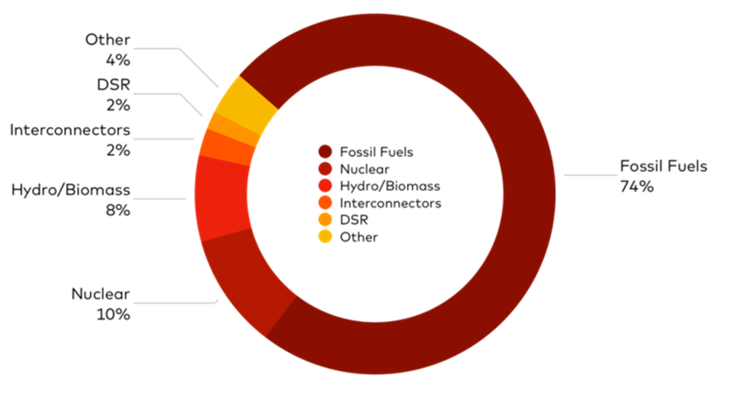

Tempus data shows that the CM has paid funds to predominantly fossil fuel providers (Figure 3). The argument is that the UK is effectively state funding fossil fuel providers to be on standby to produce power when required. The concern is that by using the CM to predominantly fund fossil fuel provision, we will continue to rely on such technologies into the future, and reduce our ability to meet Climate Change targets and agreements, which according to the IPCC are becoming more and more time critical.

On Thursday, the ECJ agreed with Tempus and ruled that the European Commission failed to launch a proper investigation into the UK’s CM when it cleared the scheme for state aid approval in 2014. As a result, the CM has been suspended indefinitely. The UK Government is now working with the European Commission to ensure a “timely State Aid approval”.

How does Brexit affect this?

All this comes at a time of high political uncertainty, especially surrounding the UK’s membership of the EU and therefore potential standing of the ECJ’s ruling. However the Brexit deal, as it currently stands on the table (14 December, 2018), will require the UK to continue to honour EU state aid rules and environmental goals post-Brexit. That we might not, is something that concerns our other European neighbours.

What will this mean for the UK, Climate Change and energy policy?

The decision to suspend the CM means the UK Government now cannot issue capacity market payments to energy firms. Additionally, it cannot hold any further auctions, including the upcoming auctions scheduled to run in January and February 2019, to secure additional power capacity for the winter of 2019/2020 and 2022/23. Will we be able to keep the lights on…? Most probably, but it will come at a higher financial cost in the short term. More importantly, it gives us the opportunity to re-think our energy market and favour truly low carbon systems – a timely decision, given the public’s increasing concerns over climate change.

Energy policy in the UK is incredibly complex. There are numerous incentives, taxes, and subsidies, all with the aim of reducing cost, reducing carbon and meeting our GHG targets, and producing a sustainable supply. A review of the cost of energy in 2017 revealed the UK’s energy policy to be lacking consistency, and was “… not fit for the purposes of the emerging low-carbon energy market, as it undergoes profound technical change”.

It’s hard to move from a dispatchable system to a more supply led system. All of our costing models and energy policies are essentially based on our ability to burn something to provide power, and the economics have developed from the traditional supply and demand approach. But this no longer stands and we need a far more sophisticated approach; including measuring the cost, carbon and energy impact of all the ancillary infrastructure associated with power production, storage, supply and demand management.

We need to move from our traditional demand based policies to those which include the whole energy system. The CM attempted to do part of this, however by doing so, it favoured fossil fuels as a mechanism to cope with short term shortfalls in supply. Now we need a truly systems based approach to deal with our increasing renewable supply. We also need to consider the wider implications of having predominantly fossil based fuel systems to back up our renewable supply, which even though estimated to be less costly, will not help us reduce our impact on Climate Change.

This ruling, whilst problematic in the short term, is a long term opportunity to change our energy policy and energy technology. Let’s embrace it to produce a truly low carbon system with active demand management systems alongside our renewable technology – enabling us to phase out our reliance on fossil fuels.

This post is based on an article by Professor Marcelle McManus, published via The Conversation on 27 November 2018.

Respond