Rod Hick is a Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Cardiff University.

The COVID-19 pandemic poses the biggest test yet for Universal Credit. Writing for the Institute for Government at the start of April, Nick Timmins argued that ‘The acid test will happen from the middle-to-end of April, when we will see whether the tidal wave of new claims to Universal Credit, prompted by the economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic, are paid out on time.’ At the time of his writing, he observed that ‘The numbers are still rising’ but that ‘So far…the system has not fallen over.’

While the government has taken unprecedented steps to prop up business and employment, spending £50 billion alone to keep people on furlough and to prevent them being laid off, many have nonetheless lost their jobs. Those that have are being directed towards Universal Credit.

Universal Credit amalgamates six means-tested and formerly separate payments, paid both to those in and out of work. It is considered the centrepiece reform for the Department for Work and Pensions of the last decade, introduced against the backdrop of swingeing austerity. Ministers claim that it simplifies what has been an excessively complex system and that it increases incentives for claimants to move into, or take additional hours of, work. It has, however, come under fire from campaigners and academics, in particular because of a five-week wait before the first payment after application, and its payment structure, where claimants typically receive payments on a monthly basis.

At the outset of this crisis, the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, announced that support for unemployed people receiving Universal Credit would increase by an equivalent of £20 to £94 per week, with changes elsewhere increasing awards for people who were self-employed, and for those receiving help with their housing costs. This was an important increase in generosity, as the Resolution Foundation noted, but one that – frankly – was built on a low base, and offered rather less than the short-term measures announced elsewhere in response to the COVID-19 (for example, those in Australia or Ireland).

But in addition to providing a stiff administrative test, the fallout from COVID-19 potentially posed a more fundamental challenge to Universal Credit – that of relevance. If hundreds of thousands of people - many of whom will have been in stable employment and will have unbroken National Insurance records - lost their jobs, this might have led to a surge of applications for one of the remaining contributory payments for people who are out of work – New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance (formerly Contribution-based Jobseeker’s Allowance).

Indeed, for much of the post-war era, such contributory payments would have been one’s initial recourse, with means-tested payments only turned to where the contribution conditions for the former were not met, or where a claimant’s needs exceeded the provisions made by contributory schemes.

The Universal Credit reform has left contributory unemployment and disability payments in place, but these have been deprioritised in political discourse and occupy an ambiguous and uncertain position within the UK’s social security system. This has continued in the fallout from COVID-19, with most policy discussions focusing on Universal Credit.

The £20 per week increase in Universal Credit award, without an equivalent increase in the other out-of-work payments, means that even someone with a full contribution record might now be better off claiming means-tested benefits, which in many cases will not have been the case before the crisis began. This increase serves not only in generosity for claimants, but will also help to ensure that the increase in the claimant count is directed towards its flagship means-tested payment. It has contributed to a bypassing of New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance, which may otherwise have grown in importance.

On 19 May, new data was published about the performance of the social security system in the weeks following the lockdown. This data shows that the claimant count – the number claiming an unemployment payment – rose by 850,000 between March and April, which hit the headlines at the BBC and beyond. To put that figure into perspective, it took more than two years for the claimant count to rise that far during the financial crisis.

We have reason to believe that new Universal Credit claimants have different characteristics than those who were claiming Universal Credit before the pandemic. Those who cannot wait five weeks for an initial payment can receive an ‘advance’ – a loan of an initial payment, deducted from subsequent payments over the course of one year.

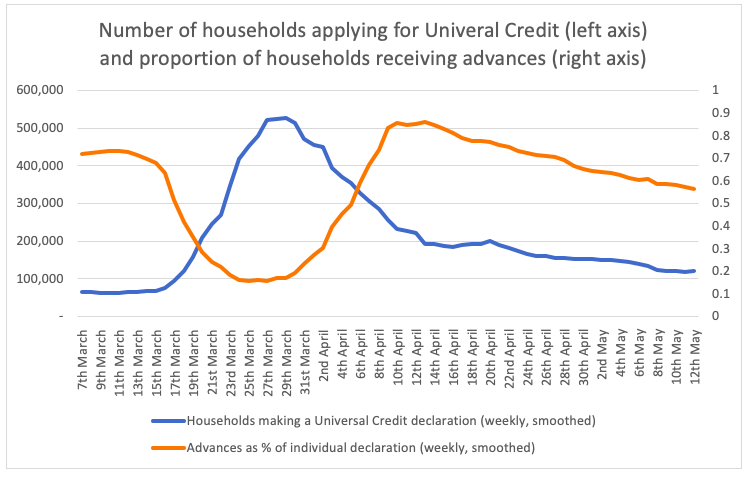

As the figure below shows, just as the number of applications for Universal Credit rose dramatically following lockdown, the proportion who would claim an advance payment fell sharply, only to rise again once application numbers fell.

It is of course possible that in those frenetic days immediately after lockdown, those who applied for Universal Credit simply did not know or take the time to consider whether they would be eligible for an advance. But it seems more likely that new claimants are compositionally unlike those who had lost their jobs before the pandemic began, and that they were less in need of such an advance. Indeed, it’s possible that many might have qualified for New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance.

We now know, following the latest data release from the Office for National Statistics on 19 May, that of the 850,000 increase in the claimant count, just 100,000 of this increase was accounted for by claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance. The rest of the increase in the claimant count was for Universal Credit.

COVID-19 has thus posed a test for Universal Credit - and not only an administrative one. The dramatic rise in unemployment, many of whom will have had no experience of relying on out-of-work payments before, raised the prospect of a rise in contributory unemployment payments, of which we have heard precious little in the last decade. The decision to increase Universal Credit – but not other unemployment payments – by £20 per week will have provided an added incentive for many to claim Universal Credit rather than the contributory payment they may be entitled to.

What we learned this week is that only a small proportion of the increase in the claimant count was accounted for by this increase. Contributory social security benefits appear, to a substantial extent, to have been bypassed. Universal Credit has indeed not fallen over.

Are you a decision-maker in government, industry or the third sector responding to the coronavirus crisis? Apply now to our virtual Policy Fellowship Programme for access to University of Bath research and expertise. Learn more.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Responses