Dr Tina Skinner is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social and Policy Sciences at the University of Bath. Dr Matt Dickson is a Reader in Public Policy in the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath. Dr Eun Jung Kim is a Researcher at the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy at Brandeis University, USA.

The UK Government recently calculated that 14 million people in the UK are disabled. That’s around 21% of the population, a figure that has steadily increased from 18% a decade ago. This matters because there are substantial differences in life outcomes for disabled people.

There is a 50% difference in household income between disabled and non-disabled people, and the income gap is growing. The employment rate for working age disabled people is just over 50%, 28 percentage points below that for non-disabled people. However, in attempting to tackle what the Prime Minister called a “gaping chasm” of employment, caution must be taken not to assume that a reduction in the ‘employment gap’ would mean a rise in economic wellbeing.

Disabled women in particular are more likely to be in part-time, junior, insecure jobs than disabled men and non-disabled men and women, so even if they have gained employment, they may continue to be marginalised by job insecurity and low income, especially in light of the economic consequences of the pandemic.

Importantly, the employment status of disabled people should not be viewed as static. For example, mental health conditions and long-term pain can mean that people move in, out and back into work, or change the hours they work, over time. Though changing dis-ability [1] trajectories are acknowledged to an extent in Government policy – as controversial ongoing capability assessments illustrate – these assessments, and negative portrayals of dis-ability in the media, have contributed to conceptualisations of dis-ability claimants as undeserving ‘benefit scroungers’.

Better understanding of how dis-ability, unemployment and economic (dis)advantage interlink over time is needed to inform both policy and public understanding. Our recent research shows that dis-ability related employment and income trajectories contrast with the image portrayed in the media, and we find that such hardship disproportionately impacts on women.

For policies which aim to improve the position of women and disabled people to become more effective, a more nuanced understanding of the intersection of dis-ability, gender, employment and income must be used to inform policy.

Policy context

Significant changes to policy have been made over recent decades with the view to enabling disabled people to gain and maintain work, by placing conditions on employers to make reasonable adjustments and not to discriminate. This was first enshrined in legislation by the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act which was subsequently superseded by the Equality Act 2010 [2].

In 1998 the ‘New Deal for Disabled People’ aimed to keep disabled people working or help them back into work. However, this was followed by the contentious Welfare Reform and Pensions Act 1999 which overhauled some of the main dis-ability benefits. Reforms were made to Incapacity Benefit and Disability Living Allowance and dis-ability elements in Income Support, while the Severe Disablement Allowance was abolished. The Tax Credits Act 1999 also replaced Disability Working Allowance with a Disabled Person’s Tax Credit.

Under the Coalition and the Conservative Governments that have followed, the austerity discourse further recast the benefit system from being perceived as a necessary safety net to a fosterer of welfare dependency and sloth - undermining the earlier positive moves to prevent discrimination at work and paving the way for cost reductions.

Indeed, reducing costs has been the focus of more recent Government employment and welfare policy changes with the Welfare Reform Act 2012, which brought in Universal Credit, and the Welfare, Reform and Work Act 2016 which took this further. For example, the Personal Independence Payments, introduced under the 2012 Act, brought in tougher eligibility assessments than the Disability Living Allowance, increasing disciplinary regimes governing access to support.

It’s not just changes to the benefit system that affect disabled people. The impact of all austerity-related cuts between 2012 and 2017 were predicted to affect homes with a disabled person more than other households. Campaigning groups, such as Disability Rights UK, and MPs have been highlighting such negative impacts and calling for Government to redress them. Similarly, our research continues to call for policy reforms to improve the economic and employment wellbeing of disabled people.

Criticism has also been international, with the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur in 2018 condemning Universal Credit, for the delay in first payments, inaccessibility, and draconian sanctions. Indeed, the House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee concluded that dis-abled people were more likely to be sanctioned than non-disabled people, despite such sanctions being harmful and not effective.

Previous work (see also: Working futures?) has shown that what is effective in enabling work for disabled people is supported/flexible/adjusted working conditions, accommodating building up work hours, less harsh reductions in benefits on entering work, and security when (re)entering or leaving work when an illness begins or ends.

In July 2021 the Government launched their new National Strategy for Disabled People. A key aim of the strategy is to enhance workplace inclusion and close the dis-ability employment gap: including workplace reporting of numbers of disabled people employed; increasing employment of disabled people in Government institutions such as MI6; an online advice hub on rights, obligations and dis-ability discrimination; piloting of Access to Work Adjustments Passports that include in-work support needs; and campaigns to change perceptions of disabled people as well as raise awareness of the help that can be gained through Access to Work.

Whilst the new strategy is to be welcomed, reducing the dis-ability employment gap will not help disabled people if it is through poor quality, poorly paid, insecure work. Such an aim must be coupled with action to reduce the income gap. Further, current documentation does not delineate any monetary investment to be made in Access to Work service provision. The barriers within the welfare system that disabled people have experienced over the last two decades are also not fully addressed.

For instance, though mandatory requirements under the new strategy are only to be used to get dis-bled people back to work “if they are needed”, the possibility of sanctions are not clearly removed; and the waiting involved in gaining monetary support from Universal Credit has not been addressed - nor has the loss of the £20 Covid-19 benefits uplift, which will disproportionately affect disabled people.

Further, there is no consideration of the difference that intersecting modes of oppression, such as gender and ethnicity, might make to disabled people. This last point is very important, as our work has consistently shown the importance of the intersection of gender and dis-ability.

Dis-ability, gender, economic wellbeing, and employment

Our analysis of the 2009–2014 Life Opportunities Survey (N = 6,159 adults) was the first UK longitudinal comparison of the economic wellbeing of disabled [3] and non-disabled women and men. We found that whilst disabled women's economic wellbeing improved in this timeframe, this did not reduce the economic disparities between disabled women in comparison to disabled men/nondisabled men and nondisabled women.

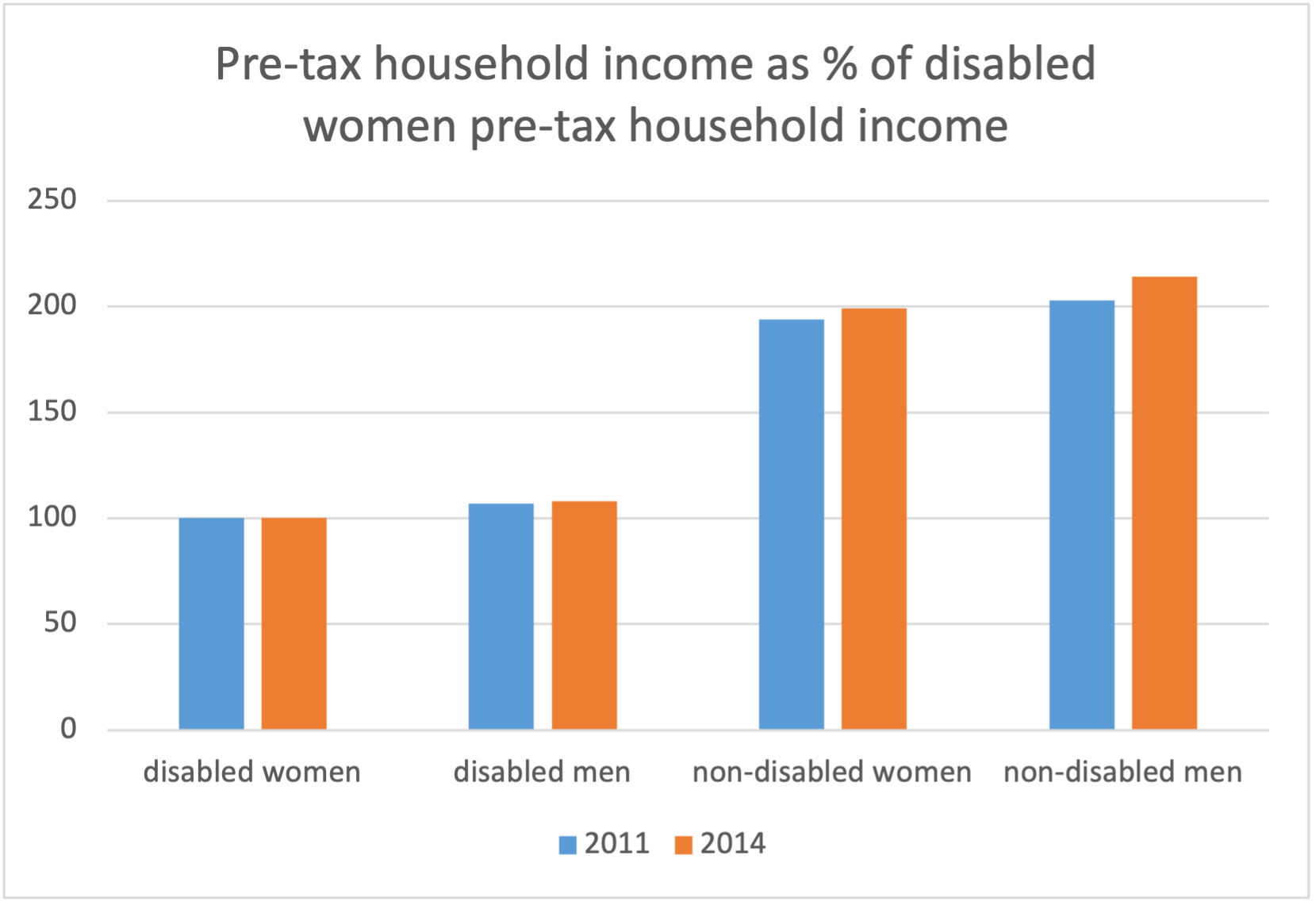

For example, in 2014 the weekly pretax household income for disabled men was 8% higher (at £467 v £433) than for disabled women. For nondisabled women the equivalent figure was 99% higher (£862) and for nondisabled men it was 114% higher (£926). These gaps represent an increase from 2011 when the figures were 7%, 94% and 103% (see Figure 1). Moreover, even though these raw income differences are reduced when considering differences in the education and socio-demographic characteristics of the different groups, disabled men (+6%), nondisabled women (+32%) and nondisabled men (+33%) continue to experience income premia over disabled women, other things equal.

Our further analysis of this data found that disabled women were also significantly more likely to be economically ‘inactive’, and most likely to be unemployed and not in full-time work compared to disabled men or nondisabled men and women.

For example, after considering differences in education and demographic characteristics, disabled men (-34%), nondisabled men (-80%) and nondisabled women (-60%) were substantially less likely to be economically inactive than disabled women. In terms of unemployment, disabled men were 10% less likely to be unemployed than otherwise similar disabled women, though this difference was not statistically significant. The differences in unemployment likelihood were significant however for nondisabled women (-42%) and nondisabled men (-55%) compared to disabled women, controlling for age, ethnicity, marital status, presence of young children, and education.

Whilst there has been a reduction in the employment gap between disabled and nondisabled people from the 1990s; this has not been accompanied by a reduction in the income gap between these two groups. In the 1990s average incomes of disabled people were 20% lower than those of non-disabled people of the same age, but far from reducing, our findings suggest a 50% difference between disabled and non-disabled household incomes. A likely explanation is that disabled people are disproportionately in more insecure, lower paid - and for disabled women in particular - part-time work.

Our intersectional analysis found that in some aspects of employment, the impact of a disabling society was greater than gender, with being unemployed, self-employed and limited in work more likely for disabled people. In others, gender had more influence: namely part-time working, public sector working, and being in a non-supervisory role, was more likely if the respondent was female.

However, when measuring the difference between disabled women and non-disabled men (the intersectional effect) we find it is significantly larger than the sum of the difference between disabled men and disabled women (the gender effect) and the difference between non-disabled women and disabled women (the dis-ability effect). As such, there is an intersectional relationship between dis-ability and gender, that amplifies the impacts on employment for disabled women.

Conclusion

Disabled women in general have less than half the household income of non-disabled women and men. However, this is not just about a gender/dis-ability income gap. For disabled women, employment is often in the most marginalised and poorly paid jobs (e.g., part-time); and an intersectional effect amplifies the impact of a disabling and gendered society.

The Government has made a good start with the New Disability Strategy by promising to tackle some of the issues faced by disabled people through the commitment to strengthen worker’s rights; raise awareness of disabled people’s rights and the service ‘Access to Work’; provide earlier positive support when returning to or trying to maintain work; ‘encourage’ employers to retain disabled employees; campaign to change public and employers attitudes towards disabled people; and hopefully implement a more enabling less draconian approach from Job Centres. But this is not enough to ensure all disabled people who want to, and can, work get the chance to thrive at work.

Recommendations

The Government should aim for all disabled people, who can and want to work, to be able to thrive at work, by:

- Introducing policies that target a closing of the income gap as well as the employment gap.

- Providing quick, flexible, and enabling support. For example:

- Dis-ability related services, such as mental health and physiotherapy, must not have a long waiting list.

- Universal Credit and dis-ability related payments should be swift and enable an adequate income that considers the costs of being disabled.

- Employers, Job Centres and Access to Work, must take a person-centred approach aimed at listening to disabled people as experts in their own needs; ensuring disabled people have choice and control in the process; and enabling the smooth maintenance and/or return to work.

- All these services need to be effectively funded long-term.

- Ensuring part-time workers are protected.

- Understanding any impact analysis and evaluation of effectiveness of a new policy needs to be intersectional.

- The term dis-ability is used to remind people that disabled people have abilities.

- Except in Norther Ireland where the DDA still applies.

- In this study, respondents were defined as disabled if they indicated having moderate, severe or complete difficulties (5-point scale: no difficulty; mild; moderate; severe; complete) within at least one area of physical or mental functioning, and their activities were limited.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond