Nick Pearce is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath.

From very early on in the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers began to track and compare government policy responses to the virus around the world. One of the most important of those exercises in policy tracking was conducted by researchers at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. In collaboration with the International Public Policy Observatory, they have recently produced a research note summarising their findings. It shows an initial ‘copycat’ period of policy convergence, followed by divergence – particularly between those countries that pursued ‘Zero Covid’ strategies and those that did not. Comparative studies of Covid policymaking are burgeoning too, helping us to understand how existing national political-economic institutions conditioned pandemic responses and public health outcomes.

At an academic conference this week at the University of Bath, co-hosted with the Yonsei University Institute for Welfare State Research (IWSR) and funded by the UKRI Fund for International Collaboration, we are exploring comparative social security, labour market and public health policies in the UK and South Korea – seeking to learn lessons from their respective responses to the Covid pandemic, and what they tell us about evolution and change in their national institutions.

On a first basic measure – the hit to GDP – there is a very wide divergence between the two countries. As a result of its early success in containing the Covid pandemic, South Korea limited the loss of economic output to -1% GDP in 2020. In 2021, growth returned to 4% of GDP, and is projected to be 2.7% in 2022. In contrast, UK GDP slumped by -9.9% in 2020, the largest annual fall in 300 years. It picked up sharply in 2021 to reach 7.5% growth but with the headwinds of inflation and war in Ukraine, this is projected to fall back to 3.6% in 2022 and zero in 2023 by the OECD.

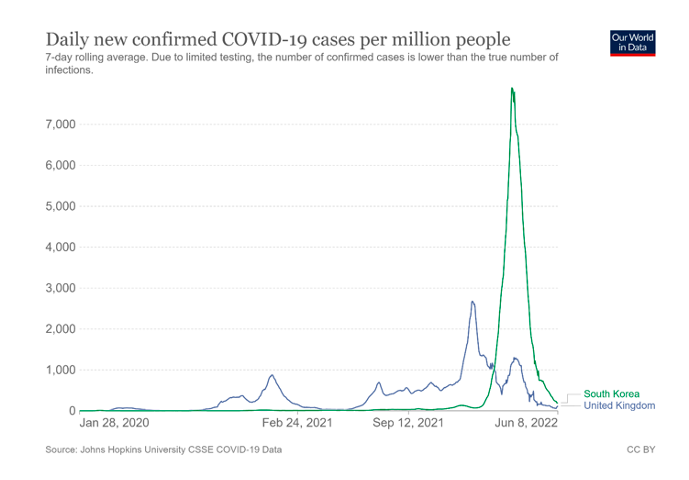

Under South Korea’s much lauded ‘Test, Trace, Treat’ strategy, Covid cases were kept low throughout most of the pandemic, but that changed with the arrival of the Omicron variant. Public health measures were relaxed and cases exploded in the spring of 2022. The contrast with the UK – which experienced higher peaks of cases earlier in the pandemic – is starkly visible in the data.

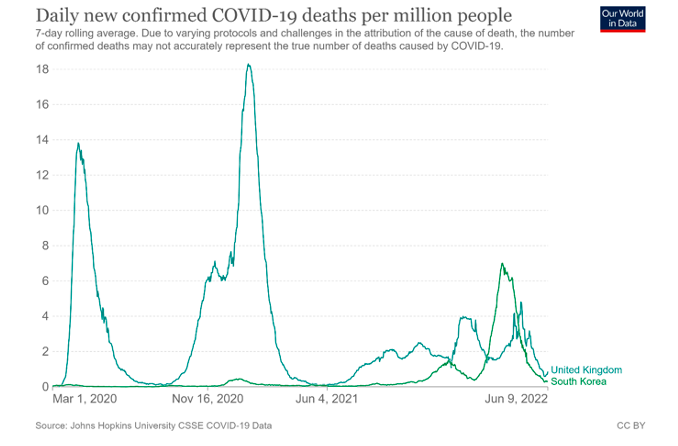

Nonetheless, South Korea’s success in containing the spread of Covid until it had vaccinated the vast majority of its population means that its confirmed Covid death rate is much lower than the UK’s:

Both countries deployed significant fiscal resources to mitigate the losses to household incomes and to support businesses during the pandemic, particularly in its first year. South Korea injected a fiscal stimulus of 14% of GDP to its economy, and tabled four supplementary budgets, in 2020, providing public health services, emergency cash payments to families, employment retention subsidies for badly affected sectors, support for SMEs and small merchants, and extensions of social insurance, amongst other measures – at a cost of hundreds of trillion KRW. Further supplementary budgets were passed in 2021 and 2022 to extend this support until social distancing restrictions were lifted.

In 2021, the UK created a Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (‘furlough’), a Self-Employment Support Scheme, a £20 a week temporary uplift in Universal Credit, and a raft of other public health support measures – providing targeted temporary support of £323 billion over 2020 and 2021. This discretionary fiscal expansion was second only as a proportion of GDP to the US in the G7. Both countries succeeded in preventing steep rises in unemployment – although the headline rates mask increases in under-employment and economic inactivity.

Coming out of the pandemic, the trajectories of the UK and South Korea have diverged again. Growth is stronger, and inflation lower, albeit rising, in South Korea. The UK has initiated another round of emergency support for families to help offset the rising cost of living – a package that it progressive and universal. But it looks set to enter a period of stagflation, caught by rising inflation and stalled growth.

Amongst many questions of interest are how far these developments in the UK and South Korea represent new trajectories for their welfare states and political-economic institutions. The radical innovation of the UK’s furlough scheme appears to owe more to Continental social security models than its own liberal institutional history, for example - while the temporary and limited uplift to Universal Credit and partial and parsimonious statutory sick pay signal continuity. Its underlying economic weaknesses of poor productivity, weak growth and regional inequality have re-emerged in full view post-pandemic. For its part, Korea’s emergency relief payments and extensions to social insurance might suggest that it is leaving behind its ‘laggard’ welfare state status, while its strong economic performance suggests underlying resilience in its national growth model. Yet in the background lurk concerns about rising household debt, real estate prices and social inequalities.

Learning the lessons of what worked, and whether the Covid pandemic represented a transformative ‘critical juncture’ or simply a period of incremental reform to existing institutions in either country, are therefore matters of substantial research and policy interest.

This blog is part of an ongoing series exploring social security, the labour market and public health in the UK and South Korea, as part of a partnership with Yonsei University, South Korea, supported by the UKRI Fund for International Collaboration.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Responses

It's also worth pointing out that during the pandemic in South Korea students were only partially affected by it. Once the pandemic hit, March 2020 was a 'working from home' for all teachers while the government worked out what to do. April 2020 was the start of online classes and from May started students coming school. At periods of confirmed cases in schools they could go to two-thirds attendance. Students finished their tests and assessments during the year and completed their compulsory minimum attedances for the year. It was all smoothly done. In the UK, it was obvious students will be affected as there was no focused and concerted policy.