Nick Pearce is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath. Joe Chrisp is a Research Associate in the IPR at the University of Bath.

The Conservative Party has been adept at shedding its skin in recent years, inaugurating regular regime changes and skilfully disowning the policy legacies of previous administrations. Liz Truss has been particularly adroit at this manoeuvre over the summer, professing loyalty to outgoing Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, while simultaneously denigrating the economic policies of his government and its predecessors. In an article for the Financial Times, Liz Truss’ prospective Chancellor of the Exchequer, Kwasi Kwarteng, described economic policy under successive Conservative administrations since the financial crisis as ‘the same old economic managerialism that has left us with a stagnating economy and anaemic growth’.

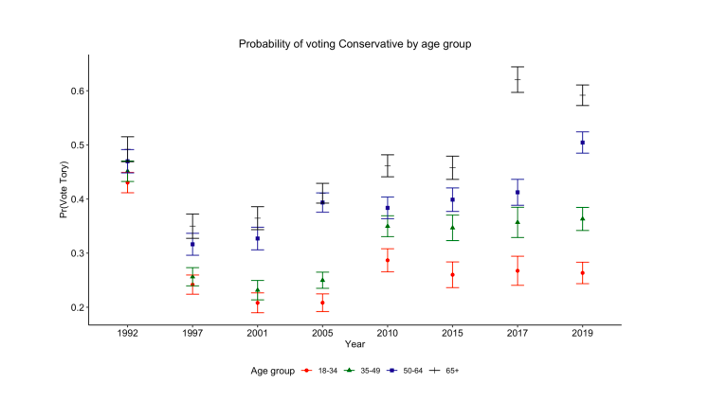

Underneath these changes of leadership, however, the Conservative Party’s electoral success in general elections since 2010 has been built on a solid bedrock of support from older voters, as the chart using British Election Study data below demonstrates. In 2017, fully 62% of the over 65s and some 41% of 50-64 year olds voted Conservative. Boris Johnson’s crushing electoral victory of 2019 was built on the support of 59% of over 65s and more than 50% of 50-64s. As older voters are much more likely to register and turn out to vote that the young and early middle aged, this dominance amongst the grey vote has been sufficient to secure repeated electoral success for the Conservatives.

It is also an electoral bloc that has been anchored in the political economy of the post-financial crisis years. Quantitative Easing (QE) and ultra-low interest rates inflated house prices and asset wealth, disproportionately benefiting older homeowners and shareholders, while consumer prices were kept low. Returns flowed to rents, rather than investment in the productive economy. Meanwhile, fiscal policy favoured older voters: while austerity was inflicted on the benefits of working age households, relative protection was given to the State Pension via the ‘Triple Lock’. Public investments in childcare, education and skills were cut, while spending was maintained in real terms on the NHS (albeit that rising demands and the Covid pandemic have placed enormous pressure on health services in recent years). The Leave vote in the Brexit referendum was similarly built on this bloc of prosperous older voters, while drawing across a segment of the retired, former Labour voting working class into the Conservative coalition.

Yet it is this electoral bloc that is now under threat – not just from post-Covid inflation and energy price shocks, but from the economic policy agenda sketched out by Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng. Inflation eats into the living standards of those on fixed incomes such as pensioners, while rising interest rates and the unwinding of QE act to bring down house prices and asset wealth. Absent of any fiscal policy interventions, inflation, and the monetary policy response to counteract it, this will begin to impact on older voters’ wealth and living standards – even if those who own their homes outright do not have to pay higher mortgages. These effects will be amplified if, as economists have predicted, looser fiscal policy through tax cuts leads the Bank of England to increase interest rates further and faster. Reversing National Insurance rises and planned Corporation Tax increases will make little difference to those older voters who pay neither. Meanwhile, cuts to public spending, the ditching of any green industrial strategy, and an avowed hostility to redistribution will curtail the room for investment in the regional ‘levelling up’ agenda.

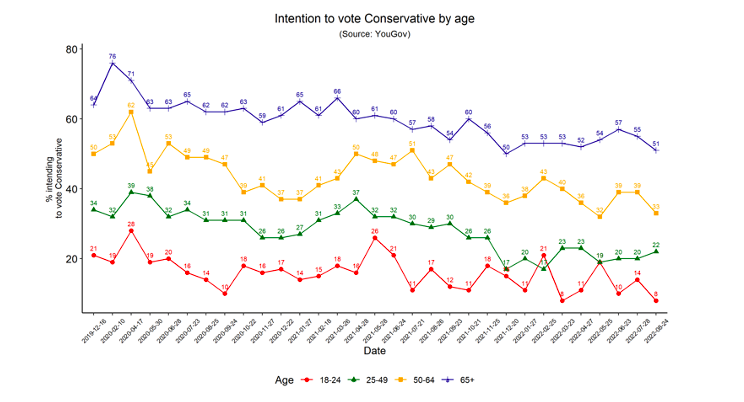

Since the 2019 general election, the Conservatives have lost some 13 percentage points in support from the over 65s in YouGov polls. An even more precipitous fall has been recorded in the 50-64 age group, down from 50% to 33% support for the Conservatives. The big swing to Boris Johnson amongst this age group was critical to his electoral success.

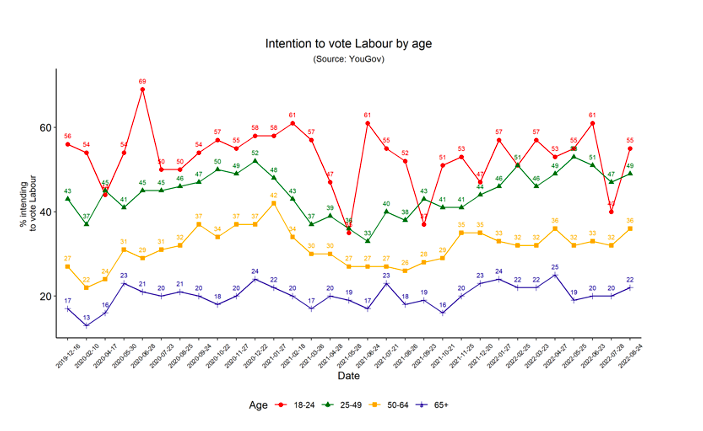

The Conservative Party will be hoping that inflation falls before the next general election, growth is renewed, and living standards start to rise. An early move to freeze energy prices is likely to give Liz Truss a poll boost, and her backbenchers will take some heart from the fact that Labour’s support amongst older voters has not risen as sharply as the Conservative vote share has fallen. Labour has done rather better amongst the 50-64 age group and these voters are likely to be pivotal in the coming electoral struggle. Given the higher turnout rates of older people, even small shifts among these voters could be the difference in key target constituencies.

Yet in seeking to embed a new, aggressively Thatcherite political economy of tax cuts, labour market deregulation and public spending cuts, Truss risks accelerating the unravelling of the electoral support that the Conservative Party has built since the financial crisis. Liz Truss is being credited with making clear choices and defining her agenda, in contrast to the cakeism of her predecessor. It may yet be her undoing.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond