Dr Aida Garcia-Lazaro is a Research Associate at the Centre for People-led Digitalisation and the Institute for Policy Research. Joe White is a Summer Research Intern at the Centre for People-led Digitalisation. Dr Susan Lattanzio is the Research and Industry Engagement Manager for the Centre for People-led Digitalisation.

People with disabilities face challenges when it comes to entering the workforce, including being disincentivised from working. This is also a pronounced problem for those who are neurodivergent – that is, people with social, behavioural or communication impairments such as autism or ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) or a learning difference such as dysgraphia, dyscalculia and dyspraxia. In this blog, we draw on data from the 2022 Labour Force Survey (LFS), conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), to explore the experiences of neurodivergent individuals in the workplace.

Our analysis reveals that, among the working-age population, 80% of individuals without reported disabilities are employed. In stark contrast, this percentage drops to only 37% for neurodivergent individuals. Contrary to popular narratives that neurodivergent people work primarily in high-skilled occupations, a substantial proportion is in fact employed in low-skilled jobs. Across the occupational skill spectrum, neurodivergent workers are also being paid less on average than their neurotypical peers. Moreover, 42% of neurodivergent employees work part-time, whereas the percentage is notably lower for people without reported disabilities, at 21%.

These disparities underscore the need of transforming perceptions and employment practices to fully harness the potential and talent of neurodivergent people. This could also benefit the wider economy, by helping to address labour shortages, and allowing companies to secure competitive advantages in areas such as productivity, innovation, employee engagement and talent retention.

Types of work

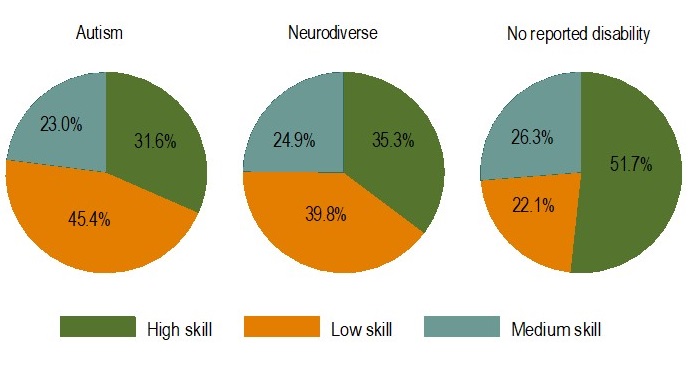

There is a popular narrative that neurodivergent people are drawn to high-skilled jobs within science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). The ONS data shows that although a proportion of neurodivergent people are employed in high skilled jobs, a substantial number are employed in low skilled, “elementary” sales and customer service occupations. When we compare neurodivergent individuals to those without disabilities, we see clear differences, with a lower percentage of neurodivergent individuals in high-skilled positions and a higher percentage in low-skilled roles.

Based on the ONS’s Standard Occupational Classification (SOC), we differentiate three skill categories:

- high-skilled occupations (managers, directors and senior officials, professional and associate professional occupations),

- medium-skilled occupations (administrative and secretarial occupations, skilled trade workers and caring, leisure and other service occupations), and

- low-skilled occupations (sales and customer services, process plant and machine operatives and elementary occupations).

We find that 52% of individuals who do not report a disability are engaged in high-skilled occupations. In contrast, the corresponding figure for neurodivergent workers stands at just 35%. At the other end of the occupational distribution, 22% of individuals with no disabilities hold low-skilled positions. This figure nearly doubles for neurodivergent workers (see Figure 1).

Closer examination of the data shows that within the neurodivergent community, autistic individuals in particular encounter considerable disparity in the labour market. A staggering 46% of autistic workers find themselves in low-skilled jobs.

Overall, the data conveys a reality in which neurodivergent individuals are disproportionately not accessing higher-paying jobs.

Figure 1. Proportion of employed individuals by job skill.

Hours and earnings

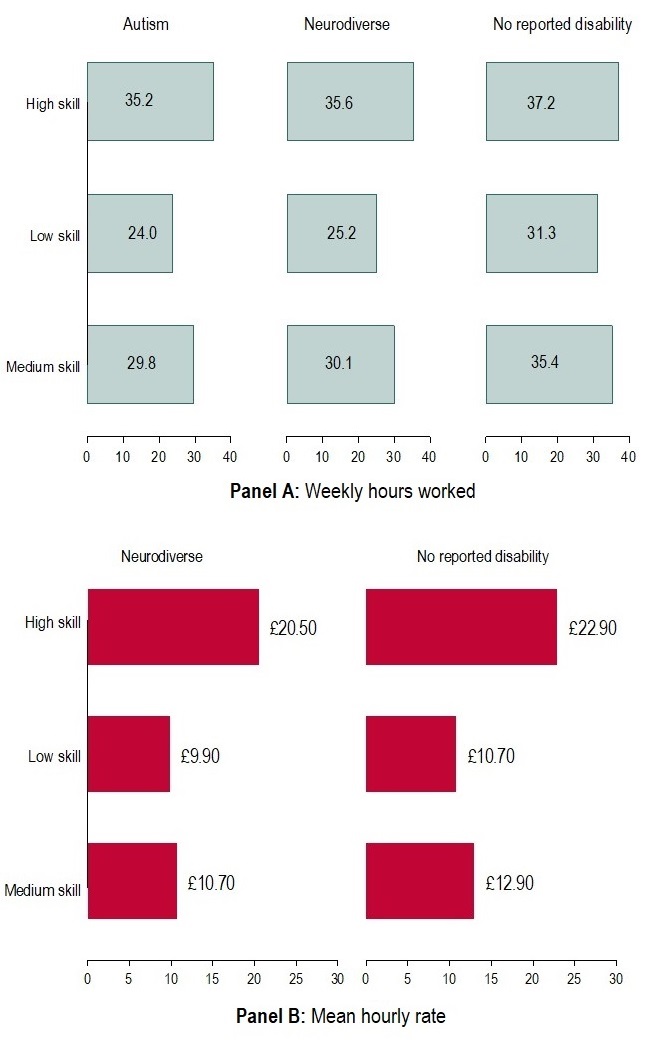

When we look at earnings and working hours, further disparities are revealed. We calculate the weekly hours worked based on skills categories for both employed individuals without reported disabilities and neurodivergent workers.

Figure 2 highlights that the largest disparities between the two groups arise in the hours worked within low-skilled occupations. Specifically, a neurodivergent worker in a low-skilled job spends a weekly average of 25 hours at work, earning an hourly rate of £9.90. In contrast, a low-skilled individual without reported disabilities works an average of 31 hours per week at an hourly rate of £10.70.

Even in high-skilled occupations, income and working hour gaps exist. Individuals with no reported disability work 37.2 hours per week on average, compared to 35.7 hours for neurodivergent individuals, with a corresponding £2.4 income gap per hour worked in favour of workers without disabilities.

Figure 2. Panel A: mean weekly hours worked by job skill, and Panel B: mean hourly pay by job skill.

Policy implications for the future

Our review of the 2022 LFS data reveals a compelling picture. Contrary to a popular narrative that neurodivergent individuals are primarily working in high-skilled STEM occupations, we find that they tend to be concentrated in both extremes of the job skill spectrum – highly-skilled and low-skilled. They also face significant pay and working hour gaps across all skill categories. The reality for neurodivergent workers is that they grapple with disadvantages vis-a-vis their neurotypical colleagues, no matter at which end of the occupational distribution they find themselves.

Although the current picture looks bleak it also presents a unique opportunity. The UK is currently suffering from labour shortages. Understanding and addressing the obstacles faced by neurodivergent individuals could help us tap into a valuable pool of talented individuals.

For this to be achieved policy makers must gain a deep understanding of neurodivergent individuals' experiences and implement initiatives that facilitate their access to education and foster their success in the workforce. In March this year, the UK government unveiled a landmark Health and Disability White Paper. While this marks a positive starting point, there is a need for more substantial institutional changes within organisations to create a truly inclusive working environment. As we pivot toward a more inclusive future it is not just about bridging gaps; it is about developing a more diverse workforce in order to harness untapped potential.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond