Author: Dr Karen Angus-Cole

‘Greenlighting the University’ was a recent seminar on the role of universities in helping societies and economies to transition to low-emission environments, hosted by the Department of Education. This blog draws out some of the key insights from the seminar, particularly around inclusive knowledge generation, participatory action research and climate education.

As knowledge producers and thought leaders, higher education institutions have the potential to play an incredibly important role in addressing the climate emergency. But is the knowledge generated by these institutions inclusive enough to actually benefit the natural world? The most recent IPCC report (2023, p.42) stated, with high confidence, that “vulnerable communities who have historically contributed the least to current climate change are disproportionately affected”. But hope abounds as it also highlights that “An inclusive, equitable approach to integrating adaptation, mitigation and development can advance sustainable development in the long term …. Inclusive processes involving local knowledge and Indigenous Knowledge increase these prospects.” (p.89).

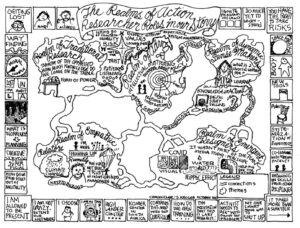

University academics do generate powerful, potentially transformative things through their research, but if wider society has not been involved then why should they trust or even care about it? Professor Mary Brydon-Miller (University of Louisville, USA) and Professor Alfredo Ortiz Aragón (UIW Dreeben School of Education, USA) made a persuasive case about how participatory action research may help to address the climate crisis by embedding rich partnerships in the research process. Participatory action research emphasises collaboration within marginalized or oppressed communities to address underlying causes of inequality whilst finding solutions to specific community concerns (Williams and Brydon-Miller, 2004). Mary and Alfredo emphasised the value of researchers reimagining their role in research and, in particular, considering how they can design research such that ownership is distributed across social interest groups (including academics, community partners and marginalised groups) so that driving social change is a shared, joint objective. Alfredo asked us: What do you find yourself doing as a researcher? How much of your work is something else - rather than traditional academic research? Upon their own reflections around these key questions, Mary and Alfredo came to the following conclusion:

“Most of it was relationship building”

Representation of the 5 realms of action researcher roles in our story, Brydon-Miller and Ortiz, 2023. The 5 realms are advocacy, empathic relaters, dynamic sense-makers, emergent designers, and traditional research.

The climate emergency necessitates cooperation through education, but this requires building of relationships based on trust. Participatory action research is about sharing knowledge but, just as importantly, is also about how those outside academia can be involved in knowledge development. In this, trust, listening, sharing expertise and recognising experience is key. In essence, the problem is solved together. Relationships are built and what we think of as knowledge production is transformed. Mary called this a shared values stance:

“A respect for people and for the knowledge and experience they bring to the research process, a belief in the ability of democratic processes to achieve positive social change, and a commitment to action” Brydon-Miller, Greenwood and Maguire, 2003, p.15.

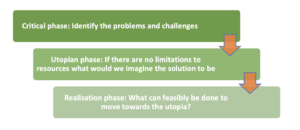

Mary went on to discuss with us where do universities need to go to address the climate crisis? What might a green university look like? She opened our eyes to Critical Utopian Action Research (Egmose, Gleerup and Nielsen, 2020) as a methodology:

This methodology encourages us to avoid separating thinking from action, or research from community. It promotes multiple ways of knowing and the letting go of misconceptions. Alfredo explained this as “opening up the way we interact to let more knowledge in”. Mary and Alfredo’s utopian vision for the green university included aspects such as authentic community engagement, transdisciplinarity, and the transformative potential of caring and mutually supportive relationships - both within and outside of the institution.

These ideas are foundational to the climate work which is being conducted at the University of Bath, which includes students partnering with both academics and professional services staff and engagement with the wider communities.

The University of Bath’s commitment and action to address the climate crisis

Alice Lowe, Climate Action Engagement and Training manager, shared the whole institution approach, which is divided into four key areas, as shown in the University’s Climate Action logo:

The University’s Climate Action Framework (CAF) was developed through a participatory and consultative process, involving staff, students, unions, and external stakeholders. Focussing in on the Education strand, there are three Es: engage, embed and empower. This Education strategy was co-created with our student climate leaders. Furthermore, the presence of the Partnerships strand highlights the role of Bath as a civic organisation and emphasises working with local, regional and international communities to enable the wider change. Just as Mary and Alfredo stressed, our University recognises the importance of coming together to address the climate crisis issue, ensuring that everybody feels like they have a voice and can participate in making progress towards addressing this huge issue.

Emily Richards, Business Engagement Manager in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, then provided a wide range of concrete examples showcasing how we are enacting the CAF. For example, the University is the first one in England to roll out Vertically Integrated Projects (VIPs), which are learning projects that enable inter-disciplinary, multi-level teams of students to work with a member of academic staff on long-term real-world projects. Many of our VIPs engage with the local community, such as the ‘Carers Centre carbon reduction journey’ . Emily also highlighted our ground-breaking work on delivering Climate Literacy to all incoming students, a project in which I also participated. Emily and I have also been involved in expanding this offer to staff. Another partnership that empowers our students and which Emily has successfully led for a number of years is One Young World. The aim is to connect and promote young leaders and give them a global platform.

One Young World Bath caucus 2023

These opportunities equip students with the skills that will help them to become leaders of the future in addressing the climate crisis.

The climate crisis is a call to action. This Greenlighting the University seminar encouraged us to reimagine our education work, consider the broader remit of our role in education, and determine how we can then use this to best effect in avoiding the catastrophic consequences of inaction in relation to the climate crisis. To enable universities to contribute to knowledge generation positively and inclusively in these unprecedented times, it is clearly valuable to consider who we work with, but of utmost importance is a consideration of how we work with them.

Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D. and Maguire, P., 2003. Why Action Research? Action Research, 1(1), pp.9-28.

Egmose, J., Gleerup, J. and Nielsen, B. S., 2020. Critical Utopian Action Research: Methodological Inspiration for Democratization? International Review of Qualitative Research, 13(2), pp. 233-246.

IPCC, 2023. Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf [Accessed 04 December 2023]

Williams, B. T. and Brydon-Miller, M., 2004. Changing directions: Participatory-action research, agency, and representation. In S. G. Brown and S. I. Dobrin eds. Ethnography unbound: From theory shock to critical praxis. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 241–257.

Respond