After decades of fast growth, a reversal in the fortunes of Fairtrade is apparent. This is particularly so for the Alternative Trading Organisations (ATOs) that spearheaded the movement, but which have become its first casualties. Dr Iain Davies asks what the future holds for Fairtrade.

I remember cold, wet February mornings standing outside supermarkets and handing out free cups of coffee in an attempt to get the supermarket to stock Fairtrade products from ATOs. I remember walking into classrooms to eager faces waiting to hear how we can change the world through trade. It is now 20 years since those first Fairtrade Fortnights, and this week it is rolling around again with the brash claim that “the Fairtrade movement is made up of ordinary people doing extraordinary things in their communities”. The energy and vigour of this early social movement has however noticeably waned in recent years. This year, it is not just the British weather which is casting a dark shadow over proceedings. The question is being asked – is Fairtrade finished?

Fairtrade’s growth for much of those 20 years was meteoric. The Fairtrade mark not only became almost universally recognised, but inadvertently paved the way for the sustainability certifications that proliferate across fast moving consumables today. The UK led the way in the mass-marketization of Fairtrade, and still represents over 25% of all Fairtrade sales globally. But the future outlook has taken a noticeable turn for the worse.

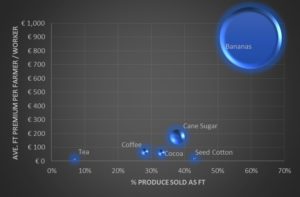

Fairtrade sales in the UK fell for the first time in 2015/16 by 5%. There is one growth area: bananas, a market dominated by one global supplier, Fyffes. Banana sales volumes are equivalent to that of cane sugar, coffee, cocoa, tea and cotton combined - all of which have seen volumes stagnate since 2011. Banana producers also benefit far more from Fairtrade membership, while smallholder-dominated categories like coffee and tea need to rely on other certification marks like Organic or Utz Certified to improve income.

In the shops, growth has been in supermarket own-label products, often produced with reduced standards and limited producer support and development. The casualties are the pioneering ATOs, such as Traidcraft, Cafédirect, Divine and Liberation, who operate to much higher levels of producer support and development, but due to price competition and reduced shelf space, have seen like-for-like sales slump in the last five years. There have also been notable failures as new Fairtrade product categories such as gold, rice and quinoa have struggled to gain traction.

To further compound the issue, one of the biggest Fairtrade brands, Cadbury, has announced its intention to withdraw from the independent certification system in 2017, following others such as Starbucks into predominantly self-verified ethical certification. McDonald's and John Lewis Café have jumped to simpler verification systems such as Rainforest Alliance. 2017 certainly does not look rosy for Fairtrade.

There is also the issue of the consumer. Still largely unable to differentiate Fairtrade from other certification systems, our research suggests that frequent Fairtrade consumption is motivated by habit, self-gratification and peer influence, not a deep affinity with Fairtrade or its producers. These consumers are unlikely to switch brands purely because of a change in certification system.

So is the end of Fairtrade nigh? The idealistic social movement I joined, which believed it could subvert the market system, died some years ago. The Fairtrade which works within the existing market system to highlight issues of social injustice, however, and provides a framework for alternative trading, has nudged many commodity companies to confront their supply chain ethics. Indeed for people of this persuasion it could be argued the job is done. The more advisory role negotiated with Cadbury could offer a future to the certification bodies as they attempt to stay relevant to a corporatized, self-accredited system of supply chain governance.

But there remains a nagging feeling in my mind that the absorption of Fairtrade ideals into mainstream rhetoric has come at a cost. Not only has there been a reduction in the number of Fairtrade standards; one voice which may be noticeably absent this Fairtrade Fortnight is that of the pioneer ATOs that spearheaded this social movement. Increasingly delisted from supermarket shelves and priced out of the market by cheaper alternatives, they are struggling to break even whilst maintaining beyond Fairtrade commitments to producers. Ultimately, with an apathetic consumer and so many rhetorically similar marketing messages, it is these farmer owned, co-operative, or social enterprise pioneers that are likely to be the first casualty of Fairtrade’s demise.

Header image by Lily under licence CC BY 2.0

Fernando Morales-de la Cruz has kindly pointed out that The Guardian has also posted an article this morning: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/feb/27/uk-falls-in-love-again-with-fairtrade-bananas-and-coffee which indicates sales have increased for Fairtrade, based on a quote by Michael Gidney. The data this quote is based on is not currently available, and certainly was not at the time of writing. Instead this article is based on Fairtrade International's data on 2015/16 sales, and producer volumes. FtF and Fairtrade International also have differing figures for previous years as well. However, notwithstanding potential discrepancies in overall sales between the UK's Fairtrade Foundation and Fairtrade International, the problems for Fairtrade in the UK are still present, and cast a shadow over this years proceedings.

Organisations can loose their way over time and come to mean different things to various stakeholders.

Reinvention or repurposing can help them to remain relevant. As a charity the Fairtrade Foundation could do worse that readdress their aims and public benefit aspirations for a future even more 'commercialised world'.