Professor Nick Pearce is Director of the University of Bath Institute for Policy Research (IPR) and former Head of the 10 Downing Street Policy Unit.

Debates about the financing of higher education have flared up in a number of advanced capitalist democracies. In the USA, Bernie Sanders has surfed a wave of Millennial anger at high college costs, graduate debts and poor labour market prospects by promising to make college tuition free. In the UK, the Labour Party vowed to abolish tuition fees for undergraduates at the last general election and saw its vote share amongst younger voters and graduates soar; while in New Zealand, the Labour opposition recently energized its youthful base with a commitment to cut fees.

Political economists have tended to explain changes in higher education policy through the lens of social class interests and how these are mobilized by political parties in different political systems (the latter typically differentiated by whether the electoral system is majoritarian or proportional, and the strength of social democratic or Left parties and Christian democratic or Right-wing parties within it). Taking higher education in England as a case study, Gingrich and Ansell (2015) argue that the introduction of tuition fees by the New Labour government funded an expansion of higher education to the benefit of a broad range of socio-cultural professionals, while ensuring that the cost was not borne by working class voters. New Labour’s reforms therefore ensured that the supply of graduates into the high skill service sector was increased without passing the costs through to the working class supporters in its electoral coalition. This fitted a pattern by which parties of the Left have come to support increased spending on universities as higher education has undergone transformation from elite to mass participation systems, but with a preference for distributions of the cost that are fiscally progressive.

In similar vein, Wren (2017) has drawn attention to the importance of increasing the supply of graduates in the transition from Fordist manufacturing economies to higher-skill, ICT-based service sector economies. In liberal market economies like the UK, higher education has been expanded to meet this demand, but deregulated labour markets and high levels of wage inequality have provided incentivizes for both individuals and governments to fund this expansion through private contributions to tuition fees. In contrast, the coordinated market economies of central and Northern Europe, which have lower levels of wage inequality and lower graduate earnings premiums, have less incentives for private co-investment in high education; here the state has to step in to ensure that there is an adequate supply of service sector graduates.

Earlier work by Iversen and Stephens (2008) situated higher education within a political-economic typology that distinguished “three worlds of human capital formation”. These were: (1) liberal-market economies with majoritarian electoral institutions producing weak vocational education and mass, privately co-funded higher education; (2) coordinated market economies with proportional representation but weak centre-right parties, producing regulated labour markets, with compressed wage inequalities and strong vocational training, coupled with high levels of state investment in education, including universities, and significant public sector employment; and (3) coordinated market economies with proportional representation and strong centre-right parties that have typically produced strong vocational skills systems, with heavy investment in sector-specific skills, but small higher education systems, weak protection for lower skilled workers, and limited public sector employment.

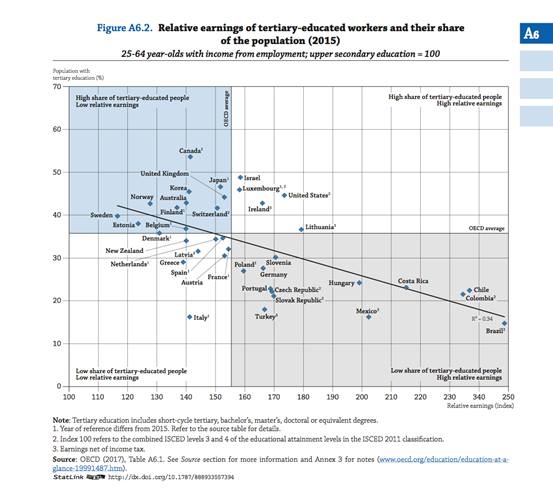

We can see how these political economic analyses play out in the most recent OECD data (OECD, 2017).

The liberal market economies are represented by the Anglophone countries (US, UK, Australia, Canada and Ireland) which tend to have higher levels of enrolment in higher education, financed by substantial private (graduate) but publicly subsidized contributions to tuition costs. Weak trade unions, in the UK and US in particular, and relatively high-income inequality, mean that graduates earn higher premiums in the labour market.

The Nordic countries – the second of the Iversen and Stephens’ typology - have relatively high rates of participation in tertiary education, but high trade union membership rates and egalitarian wage- compression institutions mean that graduates do not earn considerably more than those with an upper secondary education. They also have high levels of employment in the public sector. These countries cluster in the top left hand box of the OECD chart. Tuition is free, even though students may have to take out loans for maintenance costs.

The continental European countries with dual system apprenticeships such as Germany have lower rates of higher education participation: wage returns accrue to skilled workers in the advanced sectors, but dualist labour markets mean that there are large low wage sectors too. Higher education enrolment is lower and tuition is (largely) free. Denmark, which has a strong apprenticeship system, extensive access to lifelong learning and high trade union density is on the boundary of countries with a low share of tertiary educated people and low relative earnings for graduates. The Netherlands is another interesting case: its model of egalitarian liberalization constrains wage inequality and investments in education are spread across schools, colleges and universities. Small tuition fees are charged.

Another group of countries, such Japan and Korea have high participation rates in tertiary education, financed by higher tuition fees, but with extensive private higher education provision and low public subsidies. These have been explained by conservative political dominance in the post-war period. (Garritzmann 2016).

If these political-economic patterns, in which labour market institutions are complemented by welfare regimes, have endured across recent decades, what explains the upsurge in support for abolishing tuition fees in some of the key liberal market economies? The most obvious factor is the long aftershock of the financial crisis, which has reduced the earnings premium for graduates in the UK and elsewhere. Young people have been doubly disadvantaged when this has been coupled with austerity measures that have protected older voters’ social security benefits, while cutting those available to working age families. A further factor is that graduates have found increasingly themselves “mismatched” in jobs – that is, unable to enter professional employment or receive a graduate wage premium. (Ansell and Ginrich, 2017). This has been particularly true in Southern Europe, and helps to explain growing support for “anti-system” parties.

In the UK, substantial earnings differentials between graduates from lower income and higher incomes backgrounds – a function of the transmission of class inequalities across generations as much as the course they have studied, or the institution they have attended – may also help to account for the swing in support for abolishing fees from the young, multicultural working classes. They have seen university opportunities opened up but the promise of a decent career and affordable housing recede. They have endowed the Corbyn project with much of its political energy (though it is notable how little attention has been paid, as ever, to mature students on part-time courses, and those at FE colleges).

Political economic analyses are more limited however, when it comes to explaining the precise form that higher funding regimes take. To understand why tuition fees were trebled in England in 2012, but university funded protected, we need to factor in the institutional interests and political power of the universities themselves. Universities have an interest in protecting their funding but also their relative autonomy from the state. A cash-based loans system that switched universities out of direct student numbers control, while sheltering them from cuts, met their institutional goals, while enabling the state simultaneously to maintain higher education expansion, cut direct grants to universities and at the same time deepen a governmental reform agenda of extending competition between institutions and tying their performance assessment more closely to labour market outcomes. The class politics of university access were thus relatively undisturbed.

That relative serenity has been sharply disrupted in 2017 in the UK and elsewhere. It may presage a new wave of university funding reform.

Notes:

Julian Garritzmann, The Political Economy of Higher Education Finance, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

Jane Gingrich and Ben Ansell, The Dynamics of Social Investment: Human Capital, Activation, and Care, in Beramendi et al (eds) The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Jane Gingrich and Ben Ansell (2017), Mismatch: University Education and Labour Market Institutions, accessed at https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/BB857FC0A1BF7410917966CD6BF0A277/S1049096516002948a.pdf/div-class-title-mismatch-university-education-and-labor-market-institutions-div.pdf

Torben Iversen and John D Stephens, Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and Three Worlds of Human Capital Formation, Comparative Political Studies, Vol 41, No 4/5, (April/May 2008)

Anne Wren, Social Investment and the Service Economy Trilemma, in Hemerijck ed, The Uses of Social Investment (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017)

Respond