Dr Predrag Lazetic is a Prize Fellow in the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath.

Dangerous waters of the post-pandemic labour market

As we start to reach the end of pandemic-induced lockdowns across Europe, including in the UK, the harsh reality of the labour market consequences are becoming clear. While governments are fighting the much-feared problem of mass redundancies with unprecedented fiscal packages, it is becoming evident that the labour market consequences of the pandemic go far beyond creating mass unemployment.

As always when it comes to economic crises, they are ruthless arbiters. They tend to expose the structural features of the economy that determine the depths of the economic shock and influence the speed of recovery. Like previous recessions, the post-COVID crisis is on the one hand deeply sectoral, affecting some sectors of the economy much more than others - hospitality and tourism, for instance, which rely on sale of non-essential goods and services.

Yet on the other hand, this crisis is exposing, like no other, the problem of adequate skill supply and overinflated labour market rewards enjoyed by some segments of the labour force. Suddenly, the work of some “uniquely” skilled and usually well-suited professionals and managers becomes redundant and non-essential, while some occupations overnight become essential for any business to survive. For example, consider how important and productive phone/online customer service workers; care workers of all kinds; network and IT maintenance workers; and online marketing specialists and the like, have become.

It is yet to be seen if this increased productivity and online technology expertise of these workers will be rewarded more adequately in the labor market, as the economic ideology of human capital and skill-biased theories has argued for decades (for a critical overview of these arguments see this excellent paper by Lauder, Brown and Cheung, 2018). Or will we find that the labour market has always been a symbolic system of privilege (promoted as productivity) which valued and will continue to value certain professions and backgrounds more, irrespective of how crucial their work is?

Regardless of how that question is resolved, higher education graduates will have to navigate not only post-lockdown’s particularly ruthless, competitive and muddy labour market waters, but waters that are increasingly becoming shallower and full of new dangerous rocks on the sea-bed. To use a classical analogy from Homer’s Odyssey, graduates and any other labour market entrants will require Odyssean courage, wit and skills to pass the infamous strait of Messina between Scylla and Charybdis ahead of them.

On the one side there is Charybdis: a dangerous whirlpool of potentially long periods of unemployment with all its economic, social and personal wellbeing consequences. On the other there is Scylla: the labour market equivalent of a dangerous underwater ridge of underemployment, in which graduates risk being stranded for a long time in jobs without career prospects, in which their skills are neither used or developed, affecting their wage growth trajectory for their entire career.

Why we need to talk more about underemployment

While there is much talk about redundancies and the detrimental and scarring effects of unemployment, this blog post tries to put some light on the equally dangerous but less visible problem of graduate underemployment. Here we understand underemployment primarily in terms of skills: gaining a job that does not require a degree nor advanced skills. Although underemployment can have other, no less problematic forms, such as continuous involuntary part-time work.

The key problems of graduate underemployment relate to not just the significant proportion of graduates affected, but to the potential for long-term scarring effects on individual lives, as well as on national economic development. Although the current evidence on these effects is sparse and coming mostly from the US context, graduate underemployment potentially has negative implications for family formation, housing, long-term earnings and the repayment of student debt (as it was reported even before the pandemic). The underemployed are also found to experience lower work motivation, poorer psychological and physical health, have long-term career consequences and many other problematic effects (as the key research volume in this area outlines Maynard and Feldman, 2011).

Which countries are more likely to have higher graduate underemployment trends in the COVID crisis?

In order to see the potential scale of the future underemployment trends in the labour market in Europe, it is useful to learn from the past and see how different European graduate labour markets reacted to the increased supply of higher education graduates in the years prior to and after the financial crisis in 2008.

Differences in European countries’ and economies’ capacity to employ increasing numbers of higher education graduates in high skill occupations are substantial. That difference is a consequence of the different sectoral structure of these economies as well as policies at the national, sectoral and employer level, which lead to job design and job creation of either low-skilled jobs or high-skilled professional, managerial or associate professional jobs (which were traditionally designated for workers with higher education degrees). In many countries graduate numbers increased faster than the economy was able to create jobs in these high-skill categories. In other countries this seems to be no problem. The following figures illustrate this country variance.

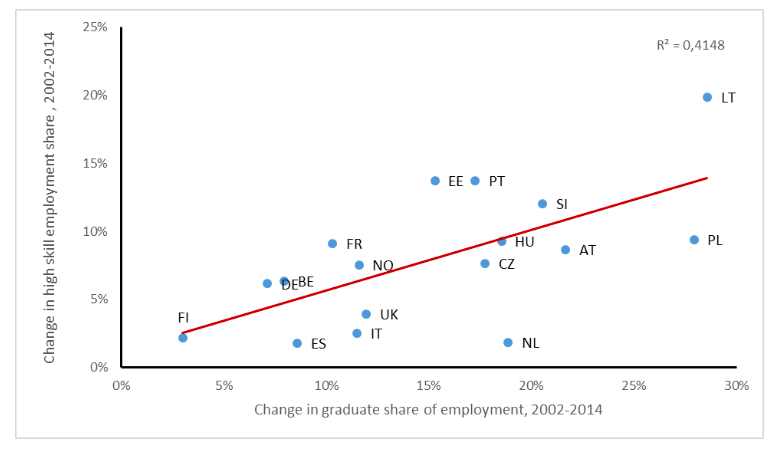

Firstly, country differences can be best illustrated by comparing the change in the proportion of the workforce who are graduates with the growth of high-skill jobs. Figure 1 shows that there is a weak yet positive relationship between the two, although in all countries, supply outpaces demand: growth in graduates outstrips growth of managerial and professional jobs. In some major European countries (Spain, UK, Italy, Poland and the Netherlands), countries lying below the fitted line, the rate of graduate supply exceeds the rate of demand for high skill jobs much more than in other countries above the line (Figure 1).

Interestingly, these major countries are the same ones in which the share of non-manual medium skill workers has increased in the past (indicating that the graduate surplus is mostly filtered down to these categories). It seems that these countries are structurally particularly bad at generating new high-skilled jobs for their large stock of graduates and therefore in danger of increasing rates of graduate underemployment in the current situation.

Poland, for instance, has witnessed one of the highest rates of higher education expansion across Europe over recent decades, but has not seen an increase in high-skill jobs matching that expansion – indeed, a number of countries with a slower expansion in the higher education sector (e.g. France) have experienced a larger increase in high-skill jobs.

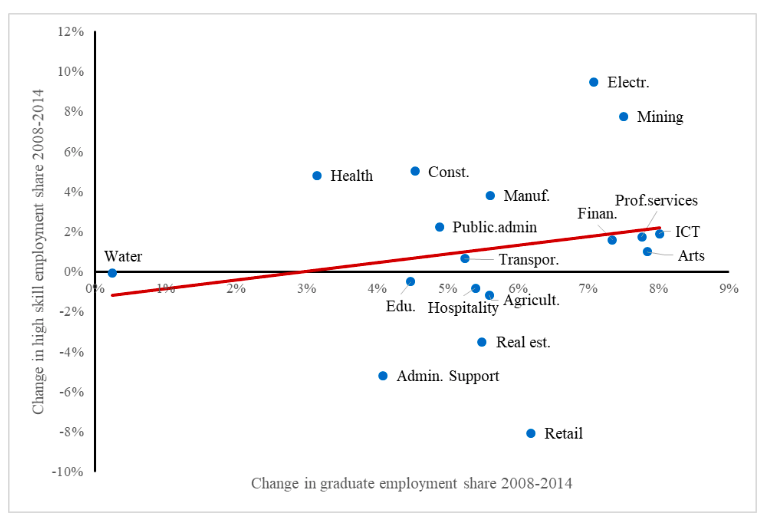

Similarly, when comparing sectors of economic activity in the same age-group of the labour force across the EU-27 plus the UK (Figure 2) we can see that in the vast majority of sectors of economic activity, the growth of the graduate labour force outpaces growth in the proportion of high-skilled jobs.

A striking finding is that in some sectors there is an evident process of de-professionalisation – a decrease in the proportion of managerial, professional and semi-professional jobs – yet regardless of that, these sectors employ higher shares of higher education graduates. These are non-trivial sectors of employment in many economies. Agriculture; the hospitality industry (accommodation and food services); education; real estate activities; administrative and support activities; and wholesale and retail, are all underemployment trap sectors, having an increasing proportion of graduates in their workforce, but a decreasing proportion of high skilled jobs.

In the case of the UK, we have an economic and employment structure that in comparative terms relies much more on services (all the key and largest UK sectors are under the fitted line in Figure 2). It comes as no surprise that both graduate unemployment and underemployment represent a looming problem for the near future.

In many COVID impacted sectors - like real estate, hospitality, and retail - redundancies and job losses will probably lead to increased graduate unemployment and even higher competition among graduates for even fewer jobs. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if some other sectors which are known more likely to create high-skilled jobs (health, public administration, professional services, ICT) will be able to absorb enough graduates to compensate for growing graduate unemployment elsewhere.

On a positive note, changes brought about by the COVID-19 crisis in these sectors – such as shifting to online operations, remote contact with customers, and the like - might also have up-skilling effects for these jobs being done by some of the already underemployed graduates, increasing the opportunity for them to use their skills. Such trends are hard to discern in aggregate statistics and require closer research and evidence gathering, i.e. to uncover the lived experience of these workers, as well as the job design and human resource policies and practices of their employers.

This blog represents an invitation for discussion in the academic and policy community, as well as for the development of information and evidence gathering mechanisms that follow not only macro quantitative trends in the labour market, but also identify and follow subtle qualitative changes which are happening in workplaces, and skill content of millions of jobs affected by this pandemic.

On the individual level, a message goes to the young Odysseuses who navigate the turbulent labour markets of today: be aware not only of the Charybdis of unemployment, but also of the dangerous Scylla of underemployment traps existing in many sectors and employers. States armed with their industrial policies; and employers with HR strategies, wage structures and job designs; now more than ever have the opportunity to help make the labour market waters a bit safer, and dangers of the Messina strait which young graduates have to pass less treacherous.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Are you a decision-maker in government, industry or the third sector? Apply now to our virtual Policy Fellowship Programme for access to University of Bath research and expertise. Learn more.

Respond