Mark Hepworth is a multidisciplinary economist and entrepreneur whose international career spans academia, public policy and business consultancy. He leads The Good Economy's research and policy work on inclusive and sustainable development.

Around Christmas, my thoughts turn to Charles Dickens and child poverty. There is a famous line from A Christmas Carol (1843) which reads: “For it is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas”. This is a heart-warming idea, but cold comfort to the quarter of a million children in London who were hungry this Christmas. For my title, I have gone to Dickens again. These words from Oliver Twist were meant to shock – but nothing has changed since the 1830s. The UK today has 4.5 million ‘Olivers’ with 500,000 more to come in 2022.

Dickens will be rolling in his grave. His writing and campaigning as a social reformer was mainly centred on London. But his fieldwork for Hard Times (1854) took him to Preston, where industrialists, landowners and headteachers were impervious to the inhuman nature of mechanised factory work and the industrial revolution. In the 1930s George Orwell also travelled north and discovered the ‘north-south divide’ while researching working class living conditions in Lancashire and Yorkshire. These great authors were the first champions of levelling up.

It is easy to be cynical about levelling up, which is why I have been slow to write this blog. But I am cautiously optimistic that it may well be an idea whose time has come. The economic efficiency and social equity arguments for it are compelling, and public awareness and support are increasing.

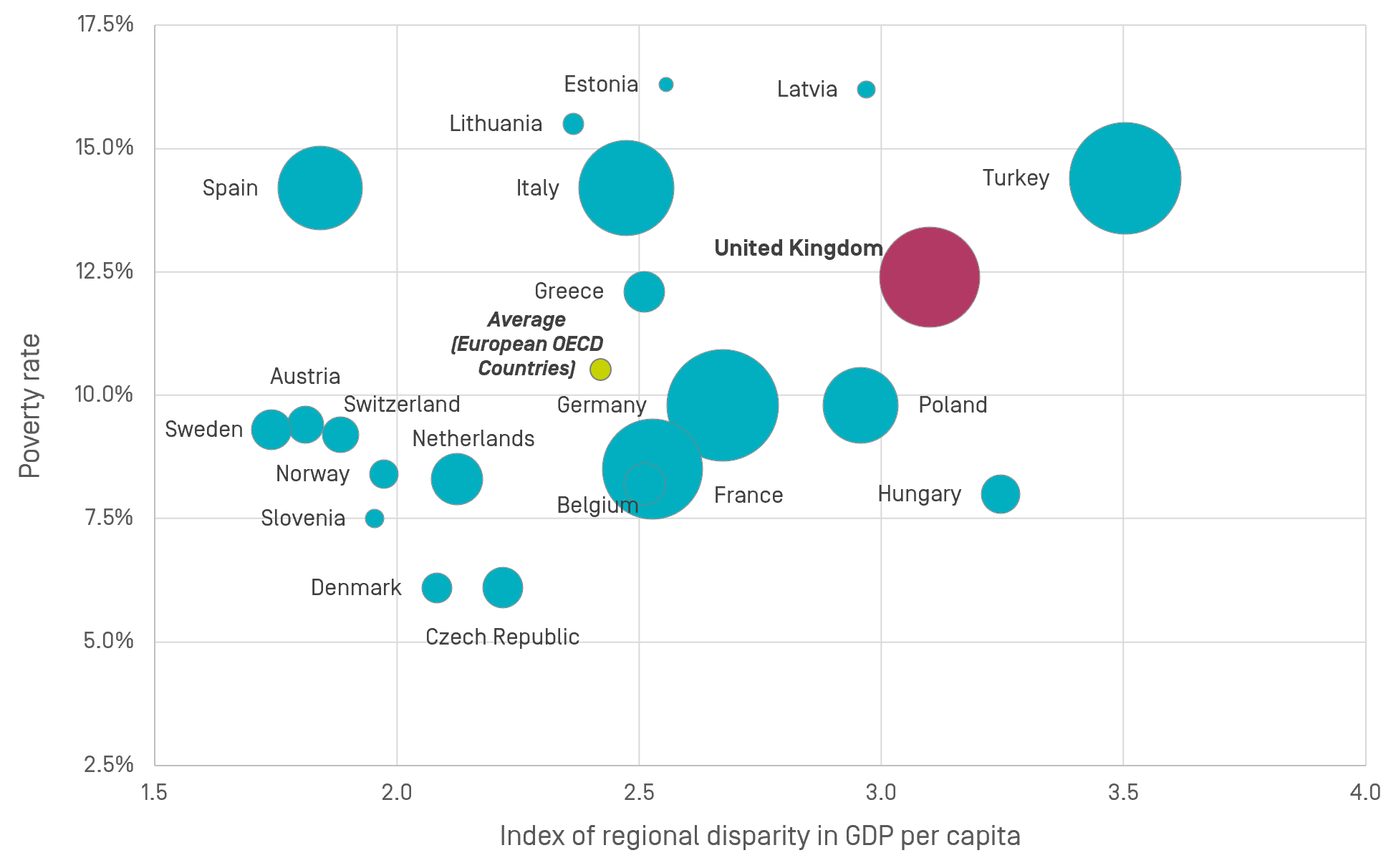

How levelled up is the UK now and where should it be? The graph below shows how social inequality (relative poverty) and regional inequality vary across OECD countries. The UK stands out as a poorly-performing outlier, its nearest neighbours being Turkey and the ex-Communist states of Hungary, Latvia and Poland.

As the world’s fifth biggest and oldest capitalist economy, the UK should have the resources and capacity to ‘level up’ to its European OECD peers. To achieve this, we have to reduce poverty by 15 per cent and regional inequality by 27 per cent.

The right mix of structural and spatial policies could bring both types of poverty down simultaneously. For example, universal affordable childcare would reduce worklessness and working poverty across low income households and areas of high income deprivation. The UK has the third highest child care costs in the OECD area (behind only Slovakia and Switzerland), which leaves some poorer families spending more on childcare than housing.

The UK’s poor showing on the 2021 Social Progress Index confirms that levelling up must extend beyond employment to health, safety, education, technology, human rights and other areas of human development. The Index includes all these factors in assessing social, economic and environmental conditions for 168 countries. The UK is ranked as a second-tier nation on the Index, along with Poland and Hungary (Turkey is fourth tier).

We need a double set of levelling up metrics that measure progress within the UK and internationally. The baseline picture is dismal quite frankly, and ‘the only way is up’ (!)

Let us now spotlight the levelling up issue that most concerned Dickens – child poverty. In 2021 the child poverty rate was nearly 40% in north-east England and London, even though these regions are chasms apart in the productivity statistics. Extreme child poverty exists on both sides of the ‘north-south divide’, as do high levels of relative inequality. A recent LSE working paper aptly titled Double Trouble shows that inequality and poverty in the UK are linked. Therefore, asking everyone to help level up while downplaying the rise in relative poverty clouds the issue – especially when it comes from the top [1].

We should not be deterred by poverty measurement problems [2]. Productivity measurement in today’s knowledge economy is highly problematic, yet improving it is the holy grail of UK national and regional economic policies. Let’s make improving Poverty another holy grail.

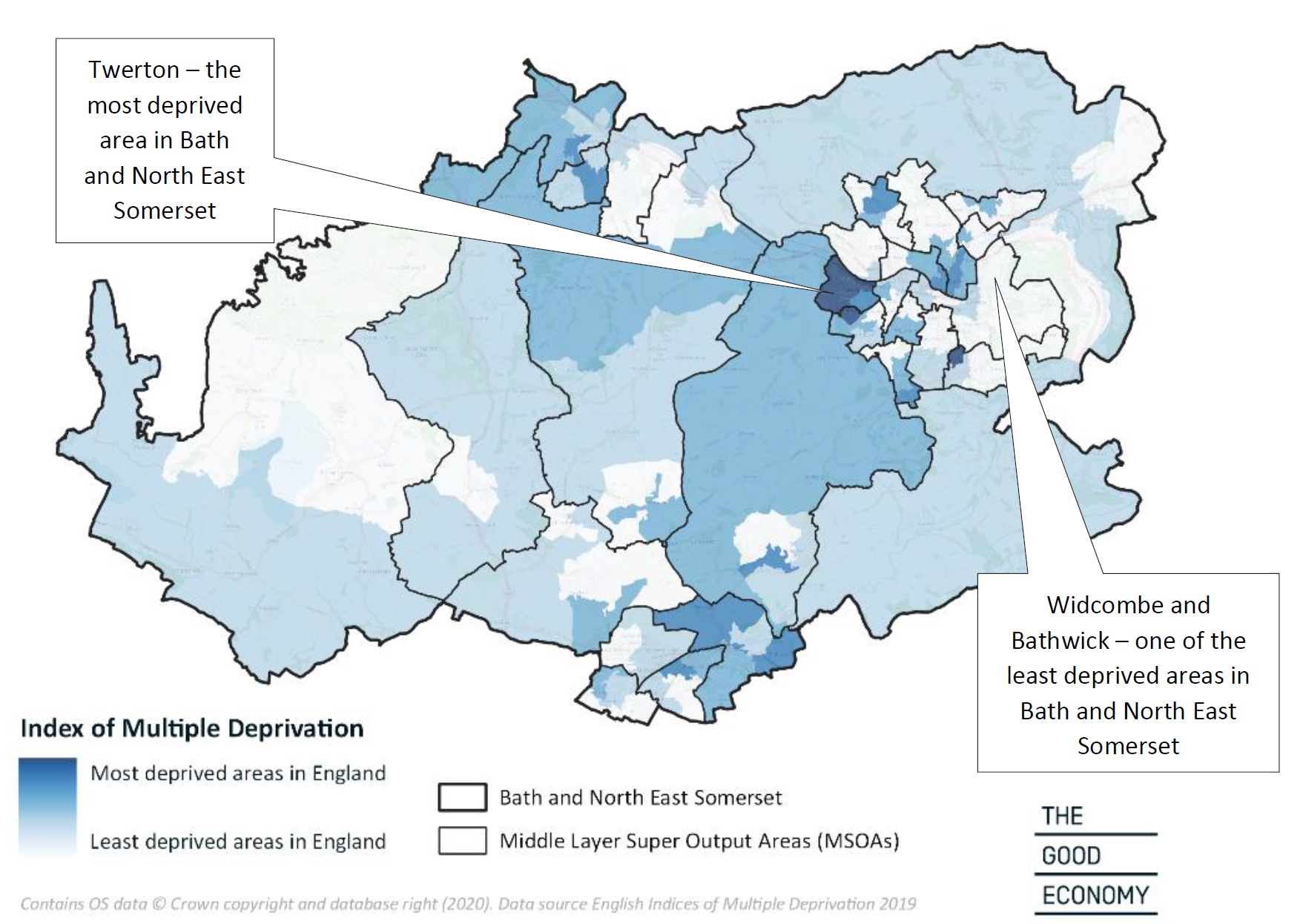

Geography matters, undoubtedly. Nevertheless we need to recognise that levelling up is a challenge everywhere in the UK. Poverty and inequality can be found in everyone’s home town, though it may be more hidden away in prosperous areas. My own ‘backyard’ is Bath in south-west England, a world heritage city thanks to its opulent Georgian architecture. Like all cities that depend on tourism and related low-pay consumer services, Bath struggles with high levels of working poverty – the root cause of child poverty.

To discover poverty and inequality here take a 15-minute bus ride out of the city centre and walk around Twerton – a vibrant community that is also the most deprived area of Bath. Its slopes offer the best views of the city, though its council estates are unseen behind your back.

To level up, every one of us needs a 360-degree understanding of poverty and inequality where we live, work and play.

Bath performs at the national average (40%) when it comes to the proportion of 16 year-olds from state schools who participate in higher education. However, this participation rate – a key indicator of social mobility and future life chances – varies from 12% in Twerton to 70% in prosperous wards like Widcombe and Bathwick (where I live).

Our world-famous Georgian city ranks seventh worst out of 333 local authorities in England when it comes to teenage inequality. So, go look in your own backyard!

The inter-generational nature of poverty and inequality suggests that the future for many Twerton children looks bleak. This is a reminder of the charity Barnardo’s stark warning: ‘Children and young people today are facing increasingly serious, complex challenges with a decreasing safety net of public services available to protect them’.

Too many young people across Britain feel a “poverty of hope”.

We must work together to level up. In particular, we are not listening properly to frontline services about the need for a UK-wide child poverty strategy [3]. Here in Bath, the St. Johns Foundation has been leading the way in tackling child poverty, working with schools, the local authority, housing associations and other community and voluntary organisations. Foundations have been at the forefront of place-based impact investing across the country. Now we need ‘all hands on deck’, with governments and private investors adding their considerable weight to social investors’ on-going efforts. We already have an Equality Act (2010). Linked to place-based policy and service delivery, it could bring more coherence and commitment to the ‘levelling up’ agenda.

The much-anticipated Levelling Up White Paper (due this month) sounds promising. There is talk of a more coherent and joined-up place-based approach to tackling social and spatial inequality, and more devolved power and responsibility for councils. The White Paper could help to fill a glaring five-year vacuum in UK child poverty strategy, if eliminating child poverty and inequality were to be enshrined as a high-level measurable objective of the Government’s Levelling Up policies, as recommended by the House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee.

Eliminating child poverty and inequality should be a cross-cutting, core objective of levelling up policies, programmes and projects.

I believe that forging these policy linkages between child poverty and levelling up at all levels is the best way forward. This joined-up approach should stretch to economic policy, including the national-local industrial strategy. We can then uproot the principal cause of poverty and inequality – the glaring lack of good jobs for everyone in the labour market. This could look like Edmund Phelps’ ‘high dynamism, wide inclusion economy’ based on ‘mass flourishing and grassroots innovation’.

To make this idea a reality, we need to invest in ‘6th Kondratieff’ sectors that will drive sustainable and inclusive economic growth well past the 2050 milestone.

According to long-wave economists, these sectors include ‘holistic’ health care (biotech but more widely, new systems of physical, psychological, environmental and social health), climate change mitigation and adaptation (‘green tech’) and digital technology (nanotech and artificial intelligence) [4]. Innovation and entrepreneurship in these converging sectors are already attracting private and public investment. Importantly, they possess the requisite economic dynamism and geographical spread to make levelling up work in the long run. Health, Climate Change and Digital Technologies are everywhere.

What is The Good Economy’s own role in all of this? Whilst child poverty is not a direct concern, indirectly, our work aims to drive more financial capital towards marginalised communities across the UK – that is, places where child poverty and inequality is more extreme. Our white paper on Place-Based Impact Investing (2021) made the social and financial case for institutional investors to engage in the levelling up agenda by scaling-up impact investment in affordable housing, regeneration, renewable energy, infrastructure and SMEs. The Good Economy is already proactive in the area of social and affordable housing. Now, we have partnered with Pensions for Purpose to launch the PBII Forum, which facilitates action-oriented discussions with all stakeholders on scaling-up place-based impact investing.

On our own doorstep, The Good Economy is involved in a levelling up project in Twerton, home to Bath City Football Club (BCFC). We are advising the club – and its majority shareholder Bath City Supporters Society – on certain aspects of a new regeneration plan. The initial plan was to renovate the club’s ageing facilities and build university student accommodation on its land which was seen as attractive to commercial investors. This planning proposal was rejected by BANES Council. The Good Economy was approached by BCFC stakeholders to identify new potential development partners and lenders to help develop viable alternatives that fulfilled the club’s aspiration of helping to reduce the long-standing socio-economic and health inequalities that make Twerton – and its young people - stand out from the rest of the City of Bath. The new development plan is designed to put the football club on a sustainable financial footing while creating a community hub and regenerating the high street for the benefit of local people. The pandemic has helped catalyse widespread interest in the project and discussions with new potential development partners are underway.

I have been writing about my own ‘backyard’, the UK. But COVID-19 has affected children across the world on an unprecedented scale. UNICEF describes it as the worst crisis for children in its 75-year history. So, opening my backyard gate, I will end with the words from a more contemporary global champion of levelling up, Nelson Mandela:

"There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children."

[1] Boris Johnson has been formally warned by the UK statistics regulator about his claim that child poverty has fallen over the past decade.

[2] The Parliamentary DWP committee: ‘The Government must now commit to implementing a cross-departmental strategy for reducing poverty, setting clear and measurable objectives which draw on the latest evidence’.

[3] Third Report (2021-22) of the House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee. ‘We heard strong views that the absence of a strategy has left the Government without a clear focus on tackling child poverty, with departments working in siloes and a lack of clear leadership’.

[4] It is especially worth reading Leo Nefiodow’s discussion of Health Care as a driver of the 6th Kondratieff

This blog was originally posted via The Good Economy on 16 December 2021. All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond