Dr Matt Dickson is Reader in Public Policy at the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath. Sue Maguire is an Honorary Professor at the IPR at the University of Bath. Their research on raising the age of participation to 18 has recently been published by the Wales Centre for Public Policy.

Every young person in the UK is required to stay in school until the end of the academic year that they turn 16. Since 2015, legislation has been in place in England which stipulates that young people should remain in some form of education or training until they reach their 18th birthday [1]. To date, this policy direction has not been pursued in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland.

The IPR has recently collaborated with the Wales Centre for Public Policy (WCPP) in looking at the impacts of Raising the Participation Age (RPA) in England and other countries around the world where similar policies have been introduced. This project then assessed the likely impact of implementing a similar policy in Wales on post-16 education or training participation, retention and attainment rates.

There is evidence to suggest that enhancing participation rates in post-16 education and training will have beneficial effects for young people, the economy and society more widely. Furthermore, a large body of research has established that previous increases in the minimum school leaving age in the UK (and internationally) led to rises in the levels of qualification attainment, earnings and skills, as well as improving health and reducing rates of mortality, teenage pregnancy and youth offending.

Until the adoption of the RPA in England, the last significant change to schooling requirements in the UK was in 1972. Under that raising of the school leaving age (RoSLA), the age at which young people could leave school was raised from 15 to 16. However, there are three fundamental differences between the RPA and the 1972 RoSLA:

- The RPA does not require young people to remain in full-time learning in school and offers the flexibility to combine work with training and learning on a part-time basis. This potentially makes implementation and tracking more difficult, given the differing options and pathways that young people can choose. It also requires the cooperation and monitoring of a vast array of both education and training providers, and employers. In contrast, RoSLA was relatively straightforward, although costly, since it required all young people to remain in school until the age of 16.

- The implementation periods and funding allocations are significantly different. RoSLA’s foundations were established in the 1944 Education Act, with a delay of 28 years to its implementation, due to the cost to the public purse, in terms of new school buildings and the additional teachers required to support such changes [2]. Plans for an RPA formed part of the 2008 Education and Training Act and were enacted in England in 2013 to cover all 17-year-olds, before being extended in 2015 to all young people until their 18th birthday, i.e. the timescale was very short. Also, the RPA was not accompanied by increased investment, with local authorities instructed to meet the costs of providing additional education and monitoring uptake from their existing overall budgets.

- While failure to comply with RoSLA legislation led to criminal prosecution of parents/carers, there are currently no penalties applied to young people, their parents/carers or employers for non-compliance with RPA legislation in England [3].

Although it is too early to assess the full impacts of RPA in England on wider economic and educational outcomes, we can see the effect on post-16 participation rates.

While post-16 participation rates in schools have increased since the RPA was implemented, this has been accompanied by a fall in the numbers of young people undertaking apprenticeships or other forms of vocational training, resulting in little change in the numbers not in education or training.

Therefore, if the policy aim is to re-engage those who leave the education system post-16 and increase the proportion of the school cohort remaining in some form of education or training, this has not yet been achieved.

It is also perhaps not surprising that the international literature review undertaken in this project found that the evidence to support an implementation of the RPA in Wales was weak. The policy design, costing and timing of an RPA, compared to historical RoSLA changes, are significantly different and help to explain why they deliver contrasting outcomes.

The question then remains as to what the policy might achieve, in terms of enhanced results, if backed by adequate funding and additional provision. This is where the quantitative analysis, undertaken as part of this project, can shed some light.

Modelling the potential impact

Without a strong evidence base specifically relating to RPA (rather than RoSLA) it is not clear what we should expect to happen in Wales, if the participation age is increased to 18.

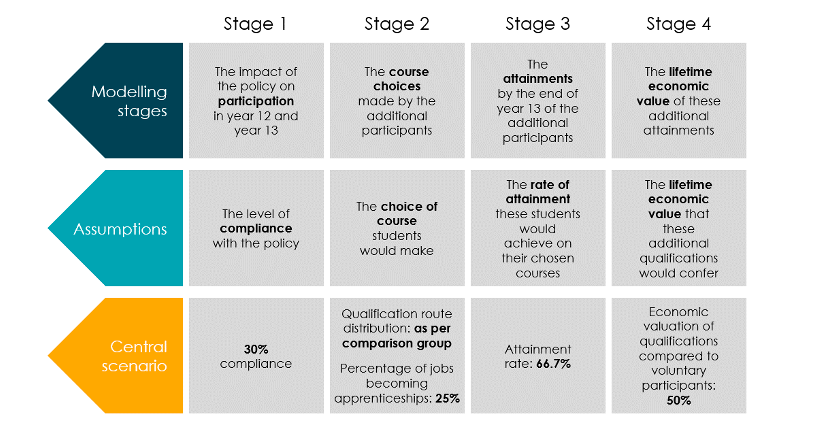

As such, we have to build a model for the impact of RPA that considers the number of people likely to be affected, what they would choose to do, what they would attain and what the long-term economic returns on their attainments would be.

To operationalise the model, we need to make assumptions for each of these modelling stages. This means that while we can choose a set of assumptions about the model parameters that we think makes most sense – our ‘central scenario’ – there is uncertainty, and the final valuation of the gross economic benefit of the policy can change quite markedly if we alter the modelling assumptions.

Figure 1 illustrates the assumptions we make for each stage of the model in our ‘central scenario’.

Figure 1: Modelling stages, underlying assumptions and assumptions chosen for the central modelling scenario

Key to understanding the potential impact on participation and the longer-term economic benefits of the policy, is the extent to which participation is increased, i.e. the degree of compliance. The tentative evidence from England suggests a very low level of compliance given the overall proportion of each cohort in education or training has not really changed. We assume that the policy has a compliance rate of 30%, which is potentially quite conservative given the English experience.

At present, given the current options, the first choice of the young people who drop out of the system at 16 is to drop out, so we don’t know what they would choose should they be expected to remain in education and training. We therefore assume that the additional participants would be distributed across the following routes:

- sub GCSE qualifications;

- GCSE or other level 2 academic qualifications;

- level 2 vocational qualifications;

- A-levels or other level 3 academic qualifications;

- level 3 vocational qualifications; and

- a mix of levels and types of qualifications;

in the same proportions as students who participate voluntarily and share similar prior attainment and socio-economic background characteristics.

However, students who voluntarily continue in education are likely to differ in unobserved ways to those who would by choice drop out. Therefore, we make the assumption that new participants attain at a lower rate, which is estimated to be two-thirds of the attainment rate of existing students with similar characteristics.

Similarly, the return on qualifications may be lower for the participants compelled to stay by the RPA and therefore, their value is calculated to be 50% of the value estimated for those whose first choice is to pursue the same qualifications.

Putting all this together allows us to estimate how many additional qualifications would be attained over and above what we would expect in the absence of RPA, as well as the lifetime discounted value of these qualifications.

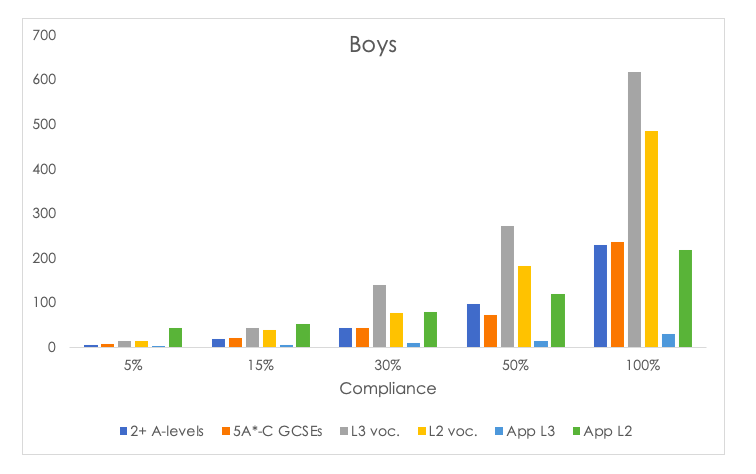

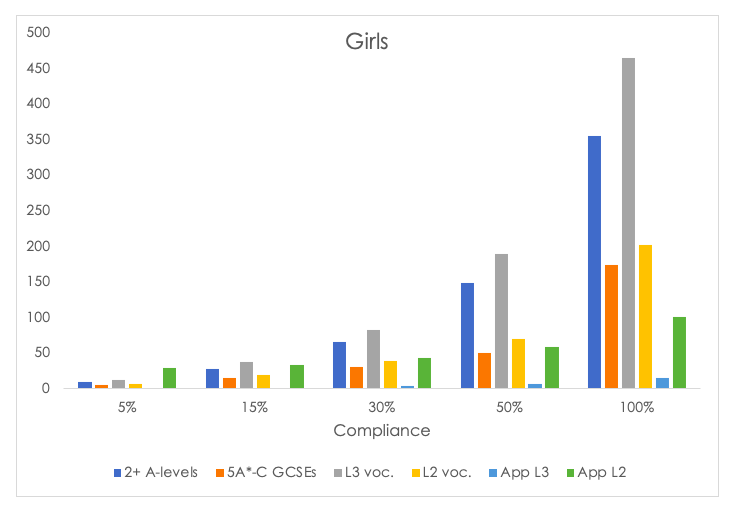

Under the central scenario, we estimate that should RPA be implemented in Wales, it would affect approximately 3% of a cohort in year 12 (around 900 students) and double that number in year 13. Figure 2 illustrates the additional estimated qualifications attained by each gender, with all assumptions as per the central scenario, other than compliance which we allow to vary.

Figure 2: Estimated numbers of additional qualifications due to RPA, by level of compliance

For boys, the additional qualifications are weighted to a greater extent towards vocational qualifications and apprenticeships than for girls, who are more likely than boys to be pursuing the A-level/AS-level path.

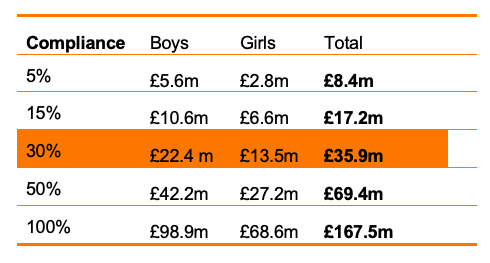

Table 1 shows the estimated value of qualifications from our central scenario, and when we allow compliance to vary between 5% and 100%. The estimated additional lifetime economic value of the attainments that these new participants would gain under our central scenario is approximately £36m per cohort. This represents a 1.4% increase in the total lifetime value of the qualifications we would expect from a cohort in the absence of RPA. As the rows reveal in Table 1, this is very sensitive to the level of compliance with the policy. The estimated value reaches £168m if full compliance is achieved and reduces to £8m if only 5% of potential participants actually complete both year 12 and year 13.

Table 1: Estimated economic benefits of the RPA to 18 in Wales for the cohort completing KS4 in 2020, central scenario assumptions

Source: Combined data from all modelling stages. Assumptions as per central scenario other than compliance and attainment rate.

The estimates are sensitive to the degree of compliance but also vary if we change the assumptions at the other stages of the modelling. As such, when fixing compliance at 30%, we get a plausible range of values from £25m to £102m per cohort depending on what we assume about routes pursued, attainment rates and the long-term economic value of the additional attainments.

It is also important to note that the estimates give the additional value over and above what we would expect to be attained in the absence of the policy, but do not take into account the costs of providing the additional education and training. Additionally, we do not consider the potential wider societal value of increased participation in terms of health, wellbeing, social inclusion and reduced crime.

Conclusions

Considering both the qualitative and quantitative evidence, we conclude that implementing RPA would generate limited benefits to young people affected, i.e young people who are compelled to participate in some form of education or training beyond year 11.

Any economic benefits from implementing RPA would be highly dependent on the degree of compliance with the policy. In all of the scenarios presented in the quantitative report, the analysis suggest that failing to provide young people targeted by the policy with options that attract them to remain in education or training post-16 will lead to low compliance, small additional attainments and commensurately small economic benefits.

What are the alternatives?

Drawing on the experience of other OECD countries, and taking into account both the qualitative and quantitative analysis for Wales, leads to the following recommendations:

- Providing a coherent and consistent post-16 offer which is aligned with the objectives of the New Curriculum for Wales;

- Focusing on reducing post-16 attrition rates and introducing a strategy to reduce early (school) leaving;

- Supporting early labour market entrants and strengthening their access to continued learning; and

- Providing sustained funding for prevention and reintegration initiatives targeted at young people not in education, employment or training.

Offering good quality pathways to all groups of learners as they approach the end of compulsory schooling is key to attaining enhanced post-16 learning rates. The quantitative analysis is not restricted to RPA but rather provides an indication of the sort of economic returns that may be available for any policy that manages to engage greater numbers of young people in full-time post-16 education or training and supports their retention and qualification attainment.

Crucially, if we are to address the post-16 education and training needs of all groups of young people, we must look beyond the full-time learning sphere. The needs of post-16 young workers must be better understood and addressed, especially those who currently fail to participate in any form of accredited post-16 learning and are vulnerable to ‘poor work’ trajectories. Also, the vexing issue of identifying and meeting the needs of young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) remains an ongoing policy challenge, which has been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Moving forward, it has, arguably, never been more important that we get the offer to post-16 learners right, in order to enable all young people to fulfil their potential, to help them make positive contributions to wider society and to assist in the challenge of re-building the economy.

[1] Or until they attain a level 3 qualification of sufficient size i.e. two A-levels, if this is before their 18th birthday, see https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/participation-of-young-people-education-employment-and-training.

[2] Balls, E. (2007). Raising the Participation Age: Opportunity for all Young People. Fabian Society Lecture, Institute of Education, London, November 5th.

[3] Dept. for Education. (2010). The Importance of Teaching: The Schools White Paper 2010. Norwich: TSO.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath. Learn more about our research on widening participation in higher education.

Responses

Yes, Wales should come in line with England for the reasons stated above.