Dr Matt Dickson is Reader in Public Policy and research lead on widening participation in higher education in the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath.

The first blog in this mini-series looked at how the new fees, loans and repayments system set out in the Government’s response to the Augar Review, might affect efforts to widen access to and success in higher education.

In its response, the Government has also established a consultation on the potential use of minimum eligibility requirements for accessing student finance for degree level study, and targeted student number controls to stem the growth of ‘low-quality’ courses. In this blog, we will look at these highly controversial proposals and how they could impact on widening participation (WP).

Minimum Eligibility Requirements (MERs)

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are independent and able to admit, or not, anyone they choose to, with almost every course listed by UCAS having a minimum entry requirement already specified (the notable exception is the Open University which has no formal entry requirements for most of its courses). However, given the upfront costs of higher education – £9,250 tuition fees per year for the majority of courses, plus living costs – setting minimum eligibility requirements to access the student finance system of tuition and maintenance loans will, for most people, de facto set a minimum eligibility requirement for attending university, regardless of what the actual minimum entry requirements of the course are.

The proposal of MERs and student number controls has led to some outcry within the HE sector. Many have raised the concern that MERs will inevitably exclude some potential students and that the students affected will be disproportionately from poorer families, hence this must damage access. Others have gone further and called the proposals “an assault on the values our higher education sector holds dear” and an attack on aspiration aiming to shut more young people out of higher education.

Stepping back from the heat of the debate on the principle of MERs, the key consideration is how they might be implemented. Part of the consultation is around where/how to set the minimum entry requirements – whether they would be a return to the old requirement of two ‘E’ grades at A-level or equivalent, or whether it should be set at a Grade 4 at GCSE English and Maths (equivalent to a ‘C’ grade under the old system). And as many have noted, setting the right thresholds will be crucial if we are to avoid damage to disadvantaged and under-represented groups.

Beyond this, it has also been pointed out that many adults enter higher education without good GCSEs or A-levels and go on to good outcomes, hence excluding them would be a backward step for WP. This is certainly true but the indication from the Government is that there would be exceptions for mature students and so this pathway to lifelong learning should not be cut off (especially given the proposal for a Lifelong Loan Entitlement, more on that in the next blog…).

One practical reason why a threshold based on the GCSEs would be better than A-levels, is that a non-trivial proportion of people, even amongst school/college leavers, enter HE via a non-A-level route. It would be a complex undertaking to work out the equivalences for the myriad additional qualifications that HE entrants undertake prior to tertiary education, and that’s before we start to think about how this would work alongside contextual admissions. There is much less variation in the qualifications undertaken at Key Stage 4, with the vast majority of young people taking GCSEs, hence it would be an easier benchmark to be working with, and easier to contextualise.

Supposing it is the GCSE threshold that is used, an important consideration is if it was in place now, how many current students would have been affected? From UCAS data it is estimated that in 2020, 8% of students (approximately 20,000) entered HE without meeting the Grade 4 threshold in English and maths. While not huge, this is a non-trivial proportion but key for WP concerns is who these students are – what is their background? That information is not available (yet) but we can make an informed guess.

Previous research shows that children from poorest fifth of households are five times more likely to miss the thresholds at GCSE English and maths than those from the best off fifth of households. Therefore, a threshold like this is likely to impact much more upon potential students from WP backgrounds and this highlights a much larger issue that we return to below.

Stepping back, it has been pointed out (and decried on principle) that the GCSE-based threshold automatically excludes the one-third of young people who do not achieve a Grade 4 in GCSE English and maths. This however highlights a key tension between widening participation and widening successful participation. A MER based on Grade 4 in GCSE English and maths will inevitably restrict participation in absolute terms, but should actually increase successful participation – at least in terms of graduate employment and earning prospects.

Our previous work with the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), using the Longitudinal Education Outcomes data, has shown that it is those with the lowest prior attainment (amongst those gaining 5A*-C including English and maths) who have the lowest earnings returns to a degree. For the lowest attaining young men in particular there are a number of degrees that are associated with negative returns. It’s important to note that these low returns are not being driven purely by subject choice or institution attended – the lower attaining have lower returns across the board. And this is amongst those who do get over the proposed threshold.

Moreover, forthcoming IPR research shows that those with lower attainment going prior to University are more likely to have poor graduate employment outcomes. And while disadvantaged students are most likely to have lower prior attainment, they are also the ones most vulnerable to misleading marketing rhetoric and less likely to have access to good advice and guidance that can help assess whether a course in higher education is the best option and if so which courses are likely to pay off for them over the long-run.

Considering fees, student debt and repayment options, we cannot on the one hand decry the amount of debt that students accrue, the effects this has to put off WP students applying, and the impact on wellbeing of carrying a burden of graduate debt that they will struggle to pay off, yet on the other hand complain about restricting HE access only to those who are likely to be able to access the content and benefit from the learning. Therefore, while introducing a MER based on GCSE attainment might have a negative effect on WP in pure access terms, it should have a positive effect on successful participation in higher education of those from non-traditional HE backgrounds, to the extent that they are currently over-represented amongst the lower attaining entrants.

Student number controls

The consultation will also look at the potential for the reintroduction of student number controls. The Government has been keen to stress that this does not mean a cap on the overall number of students who can attend higher education, which is very important given the social gradient in who attends HE – any limit on places would likely see those from the least advantaged backgrounds squeezed out of the places.

Instead, the Government’s stated aim is to ‘prevent the growth of low-quality courses’. The key will be how ‘low-quality’ is defined, and the level at which number controls might apply – by sector, provider, subject, or even level/mode of study. The suggestion is that low quality will be defined as courses with high drop-out rates and low proportions going on to graduate jobs, but there is also a feeling that perhaps earnings outcomes are again under consideration as a relevant metric.

As we’ve written about before, using earnings outcomes or an earnings-based metric of the returns to a degree would not be sensible as there are so many other factors that influence earnings outcomes, not least (future) demand from the labour market. Graduate level employment is a better metric given that in the UK we do have a relatively high level of graduate underemployment and while for a variety of reasons graduates may choose a job that does not have high earnings, it is less likely that individuals go to HE and then voluntarily choose a job that they don’t need their degree for.

Even these sorts of metrics are however difficult to implement. For example, there may be gender or ethnic dimensions to course outcomes – so what would that mean for a course if it has good outcomes for some students but not others? Would women be able to take certain subjects at HEI but not men? All sorts of questions are opened up when we start to think about how number controls would actually relate to course outcomes, and as David Willetts has pointed out, trying to micromanage admissions is a big change to the current system and the cure might end up being worse than the disease.

This consultation also arrives at time when the Office for Students (OfS) has also just been consulting on the targets it will set HEIs when assessing their compliance with the requirement (B3) to deliver positive outcomes for their students. The proposals are that targets be related to students’ progression to the second year of a course, completion of the qualification and progression to a graduate job or further study. How student number controls would work in tandem with the OfS’s powers here, or whether they are even needed in light of the existing powers of the regulator, is yet to be explained.

Set against this is the reality that with tuition fees frozen and inflation close to 8%, HEIs need to grow student numbers in order to maintain their incomes. But allowing this growth in student numbers to be unrestricted will see the unit of resource per student eroding, and inevitably the quality of the student experience falling.

There are alternative options that can address falling values of the unit of resource without complex micro-management required, such as the controlled growth promoted by the pre-2012 tolerance band system approach. The evidence suggests that the changes since then have resulted in very little change to WP metrics, and so any cost in terms of widening access is likely to be small.

The bigger picture

Returning to the question of who is most affected by a potential MER, it highlights a much bigger issue for WP in HE. The single most important factor affecting differences in HE participation between under-represented groups (typically those from more disadvantaged households) and those from more traditional higher education backgrounds, is attainment at GCSE.

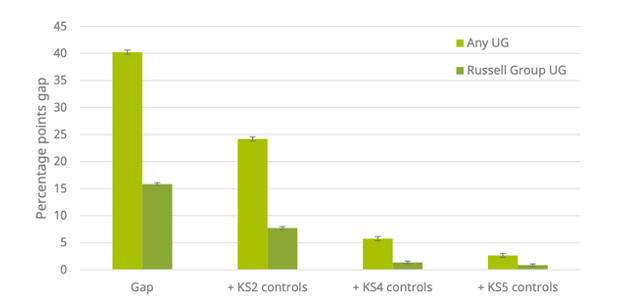

As Figure 1 below shows, there is a large raw difference in access to HE between those from the least well off fifth of families and those from the most well-off fifth of families: 40pp. However, once we control for prior attainment up to Key Stage 4, and so compare students from different backgrounds who attain the same results at GCSE, the gap reduces massively to just 5pp.

Notes: taken from IFS work on access to undergraduate degrees using the LEO data available here: https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/Family-background-and-access-to-postgraduate-degrees__.pdf.

Figure uses results for the 2002 GCSE cohort, using English state-school students only. SES is based on several measures combined into one continuous index, as described in more detail in Section 2. The first bar shows the raw percentage points gap in undergraduate attendance between those from the top and bottom 20% of parental SES. The KS2, KS4 and KS5 bars add controls for age 11, 16 and 18 test scores respectively. Undergraduate access is based on starting any first degree undergraduate degree course by age 30.

Every stage of education has the responsibility to open-up opportunities and ensure that students from lower socio-economic backgrounds and other disadvantaged or under-represented groups are able to access education on an equal footing. HEIs up and down the country continue to work hard to improve access and success in HE. But it is clear that closing the gap in GCSE attainment would have much more of an impact on WP than anything HEIs are able to do. For this reason, aligning the existing incentives of schools – to get pupils across the Grade 4 threshold at GCSE English and maths – with the MER for HE entry might not be a bad thing, as Mary Curnock Cook, the former Chief Executive of UCAS has recently argued.

So while the prospects for MERs and some form of student number controls may have impacts on widening access to and success in HE, depending on the final details of how they are implemented, the bigger picture is that if we really want to improve social mobility and increase access to HE, raising attainment at 16 will have a far more dramatic impact than changes to fees, funding or arrangements around minimum eligibility requirements or number controls.

In the final blog we will look at the other elements of the Government response, chiefly the Lifelong Loan Entitlement.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath. Learn more about our research on widening participation in higher education.

Respond