Meet Jon Noble, a chemical engineer whose thirst for knowledge keeps him coming back to the world of academia. Despite having a busy schedule, Jon's passion for his topic also compels him to take part in the occasional public engagement activity.

In March, he volunteered as a speaker at Science in Radstock. Although the experience was a bit of a rocky road, he still managed to win his audience over, and came back with a few valuable lessons...

Sitting in front of a blank presentation with just one week to go, I wondered if I had made a mistake in volunteering to present an hour-long talk to a group of science enthusiasts at a working men’s club in Radstock. Three months had passed since I had signed-up, and all good intentions of preparing the talk well in advance had evaporated amidst course modules and report deadlines. The empty screen in front of me glared at me, staring judgingly, stubbornly refusing to write itself. Where to start?

With the basics. Thanks to the excellent training provided by the CSCT, in conjunction with the Science Made Simple team, I already had some idea as to the first point that I needed to cover: know your audience and your message. Back in mid-February, I had sat down with Helen Featherstone and Rob Cooper from the University Public Engagement Unit to grill them for information over a cup of coffee. The Science in Radstock talks attract a wide range of people, some with a deep technical background, and others with a passing interest. The key, Helen said, was not just to focus on the science, but the personal aspect of it; why I had chosen to study at the CSCT and why it was important to me.

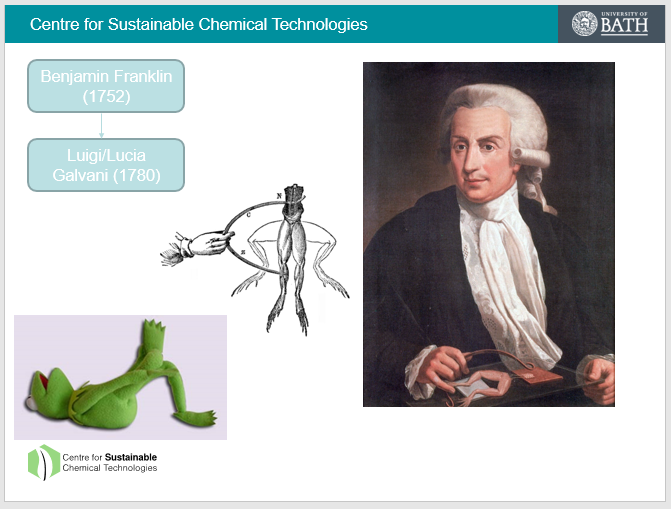

As anyone who has asked me about my PhD topic (Induction Heating of Chemical Reactors) will know, it takes me around ten minutes to explain my work to even the most technically savvy person. An idea started to form – if an audience is interested in learning about the people behind the science, why not provide them with a flavour of the people behind the science? A biographical history of electromagnetism. Rather than explaining how an induction heater works, I could just show them by replicating the experiments used by the scientists and engineers that discovered the underlying physical laws. Using experiments to demonstrate the science also fulfilled another requirement of an hour-long talk: it might be difficult to talk for an hour, but it’s also equally hard to sit through someone talking for an hour. The demonstrations provided hooks to re-engage the audience’s interest in the talk.

Four days later, I had my presentation: an introduction to why I had returned from industry to academia, not least due to the pricking voice of my environmental conscience, and the importance of tackling climate change; a segue through a brief history of electromagnetism, from the ancient Greeks through to James Clarke Maxwell; and an overview of my specific PhD topic and its wider implications. Having practised it several times over, I headed over to Radstock with boxes full of balloons, potatoes, power supplies, nails and fizzy water.

Arriving at the venue, I encountered my first challenge. I know from past experience that the best laid plans never survive their first encounter with reality, and this was no exception.

- Lesson 1: Know your venue layout, and plan accordingly

The projector was located at the back of the room, which meant that my laptop needed to be at the back of the room. The webcam that I was using to project some of the demonstrations needed to be attached to the laptop, so I had to run back and forth between the front and the back of the room between presenting and running demonstrations - much to the amusement of the audience, as I’d like to imagine.

- Lesson 2: Be prepared to meet the experts in the room

On arriving at the venue, I was introduced to Richard Ellam, one of the Science in Radstock organisers, a retired science historian. Suddenly I had the added pressure of presenting a hastily prepared science history lesson to someone who had devoted their entire career to the topic. However, he reassured me that he was sure that my talk would be interesting and so, with a few deep breaths as the final members of the audience filed in, there was nothing left to do but start.

- Lesson 3: Demonstrations might not work – accept it, and move on

The laws of physics may stay constant, but that doesn’t mean that they won’t desert you in your hour of need. An experiment involving static electricity completely failed to work, on reflection due to a much more humid environment than when I had practised it. I also had an awkward moment when a magnet got stuck in a tube exactly where it wasn’t supposed to.

So try again, and if it doesn’t work, move on. If you can make a joke out of it and explain what should happen, the audience will sympathise with you, and it makes for a more memorable talk.

- Lesson 4: Prepare for questions!

A slightly sweaty hour later, the talk was over - or so I thought. I hadn’t prepared for the full range of questions from an audience that was clearly very switched on to all aspects of sustainability. Fortunately, my background and training in the CSCT enabled me to provide some great examples in response to these questions, and I left the venue both relieved and impressed with the engagement that the general public has with sustainability.

- Lesson 5: Remember to enjoy yourself

It’s easy to get caught up in deadlines and in the stress of standing up for an hour, on your own, in front of a group of interested people. This is made a lot easier if you can enjoy the journey. The advice from Helen Featherstone rang true - I enjoyed learning about the lives of the scientists and engineers that I was researching as much as I’m sure the audience did. Remember that your audience isn’t there to catch you out – they are there because they are interested, and they want to see you succeed, so take it easy and relax.

The next day, I received some email feedback saying that my talk was “one of the best” they’d ever had. I was glad that the hard work had paid off, and this is as much a testament to the training provided by the CSCT and the Public Engagement Unit at the University, as it is to the long hours of preparation.

I have found that there is no substitute to practically applying the public engagement skills taught in the centre, and highly encourage all students to get involved in public engagement activities such as those offered by Science in Radstock.

Respond