Project Leader: Dr Alessandro Narduzzo, Department of Physics

Unit: Introduction to Quantum Physics

This is a case study of one of the University's funded pilot Flipping Projects, looking at the motivation for flipping, the methods used, lessons learnt and impact.

Motivation

Interactivity in lectures helps keep students alert and attentive; if student engaged participation is actually established, the reception of unseen study material can be more effective; if in addition to that, the study material is not unseen but has already been explored by the students, the active practice of questions on the material, suitably linked to the resources provided in advance, could make the learning even more effective and lasting, deeper, at times transformational.

The use of ‘clickers’ in higher education is not a novelty anymore; I introduced some clicker sessions when teaching a maths for physicists course, and given the positive reaction of students to that, decided to introduce clicker sessions also in the Year 1 physics unit Introduction to Quantum Physics. For both the maths and the physics courses, these sessions were really problem solving sessions – with problems often taken from practice problem sheets – where students had the additional opportunity to see the answers their colleagues had given and go back and reconsider the problem, while interacting with their peers.

Flipping, the attempt to make study resources available to students (about a week) in advance of a session during which the contents of those resources are used, practiced, applied, discussed and critiqued, was then a natural development in the attempt to make contact time a ‘many way’ lively interactive meeting on a topic rather that a mostly one directional (lecturer to audience) traditional rehearsed and staged presentation.

Work done early on in the US (Hake, Mazur, Dufresne) and more recently at the University of Edinburgh (Simon Bates and colleagues), supports the notion that ‘flipped teaching’ leads to improved, deeper learning.

The flipped classroom

Relevant materials (consisting of Prezis, videos and handouts to read with a few preliminary quiz questions) were made available to the students 5-7 days before the session via the online VLE (moodle); students were asked to explore the materials in preparation for the interactive ‘flipped’ session. The sessions consisted mainly of a series of relevant clicker questions that the students were asked to answer individually first, then discuss in small group and then answer again. Comments and additional feedback was then provided to the whole cohort.

Lessons Learnt

From the student feedback received (‘Using clickers with powerpoints was very useful and helped give a better understanding of the unit. The flipped sessions are also very useful and meant that problems could be done within the lectures and so model answers could be collectively created’; ‘I really dislike flipped lectures – if you do not understand something from the online resources there isn’t really an opportunity to go over it in lectures because Alex just does questions on the material and if you didn’t understand it then you couldn’t answer the questions and it made me feel a bit stupid’), there appear to be comments both in favour and against both ‘clicker sessions’ and flipped sessions. The most important point now is to address the issue of making the interactive sessions as relevant and useful for as many participants as possible. From another student: ‘The flipped lecture layout did not aid my learning. Having one flipped lecture was manageable but when we have 4 flipped lectures in a row, I feel my understanding of the content is not as great as it would be had we been taught by a lecturer. For the first few flipped lectures, I had already seen the ideas at A level but for ideas not seen at A level, I feel that it is a bad idea to use flipped lecture. When trying to teach myself the flipped lecture content, using other textbooks is hard as sometime they use different notation to the lecturer. I also found the flipped lectures were pointless, as when we actually had a lecture, I had already learnt the content and time was spent doing quiz’s and questions rather than going over material more in depth and making sure it was understood properly.’

Thanks to some peer observation, a number of strengths and weaknesses of these sessions have been further identified, in particular: some of the ‘clicker’ questions were too easy/superficial; and some of the discussions that followed the various clicker questions were too superficial. More work needs to be put into design and delivery of interactive sessions to include a variety of elements in them, including less but ‘deeper’ clicker questions, more effective peer discussion and some “5 minute mini-lectures” to consolidate crucial conceptual points, or to present further related topics/applications. While some of these changes have been introduced in response to feedback received on the flipped sessions run during 2013-14, more work is needed to further develop more resources and to achieve a cohesive and consistent structure for the unit as a whole, without the apparent disruptive introduction of flipped sessions in between usual traditional ones. Students in fact go through the first half of this unit largely following the traditional lecturing style and come to flipping only in parts of the second half. Sometimes negative feelings and impressions associated with flipping but really caused by structural/organisational and presentation problems can lead to students’ decisions not to engage with the activities proposed, or simply to a dislike for those activities. Further thought needs to be given to try and engage those who appear, from the beginning, unwilling to actively interact.

Impact

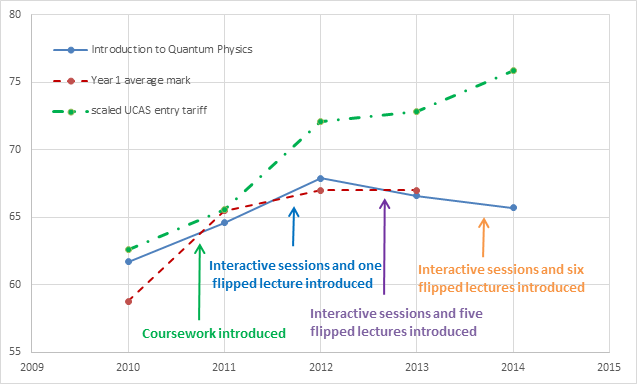

If one assumes the final mark each student gets on a unit to be positively correlated to the depth of learning (in other words if one considers the final overall mark – for the unit considered here made up of 20% coursework and 80% exam – as a measure of student learning), then monitoring average marks for the unit before and after changes in the learning & teaching methods introduced should provide evidence in favour or against the new developments. The figure below shows the average marks for the unit Introduction to Quantum Physics over the five academic years from 2010-11 to 2014-15. In order to make this number more meaningful, it is here plotted together with the overall average mark a student cohort got at the end of their first year, and together with the average UCAS entry tariff for Bath Physics (scaled by the average Oxbridge UCAS entry tariff for 2014). The following summarises the changes introduced in each year.

- 2010-11: no interactive sessions, no flipping, no coursework

- 2011-12: no interactive sessions, no flipping, coursework - short writing task

- 2012-13: interactive sessions, one lecture flipped, coursework - short writing task<

- 2013-14: interactive sessions merged with five flipped lectures, coursework - short writing task

- 2014-15: interactive sessions merged with six flipped lectures, coursework - short writing task

The ‘quality’ of students entering our Physics and Maths & Physics degrees – as measured by their average UCAS entry tariff – has been going up every year, and so have the Year 1 average mark and the Introduction to Quantum Physics mark up to 2012. From 2012 to 2013 the Year 1 average has remained flat (the 2014-15 Year 1 average is not yet available), while the Introduction to Quantum Physics mark has dropped slightly for two consecutive years. While these recent changes are not dramatic and within the error bars of the data points, it seems clear that the introduction of flipping as it was done has not produced any marked improvements in the unit’s average student grade. One could even argue they may have worsened the final mark somewhat. One should also consider several other variables that do play a role in determining these data, making any conclusions only speculative at this stage. What clearly emerges from the feedback received and the data is the need to construct a more cohesive unit where flipped and non-flipped elements are integrated better and complement – rather that contrast – each other, and where interactive sessions are designed carefully to focus on in-depth, conceptual aspects of the material being considered and moderated with attention to detail and flexibility. Published work reporting on student improved performance thanks to flipping always flipped entire courses and not just small parts of them in a time-wise uneven fashion; this point may well be important.