“Few individuals in the history of education have had greater impact on education policy and practice than Benjamin S. Bloom” (Guskey, 2001)

Bloom’s Taxonomy has shaped every area of educational practice from the learning outcomes and assessments we set, to the way we design and deliver teaching and learning activities. Whilst the intention of this article is not to question the usefulness of the model in itself, there is potential value in considering how we as teachers apply and interpret Bloom’s Taxonomy, particularly when developing inclusive teaching practice.

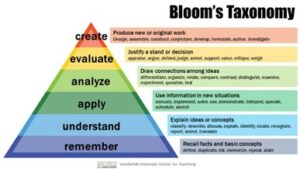

The Taxonomy (See figure 1) enables us to take a broad view of the thinking skills which students require from their ability to remember, understand and apply, to the skill of being able to analyse, evaluate and create new ideas. Bloom himself is said to have commented that the original Taxonomy is “the most cited and least read book in all of education” (Anderson, Krathwohl, 2001), recognising that there is therefore potential for the tool to be unintentionally misinterpreted or misapplied.

Figure 1: Bloom’s Taxonomy

As mentioned, my intention is not to question the usefulness of the Taxonomy, but rather to encourage us to reframe the way we use it as a tool to shape our observations, assumptions and interpretation around student learning and assessment. This is particularly important when we think about neurodiversity and learners in our classrooms who may be neurodivergent. The term Neurodiversity, credited to the Australian journalist, Judy Singer and the US journalist, Harvey Blume, refers to “the different ways that we all think, move, hear, see, understand, process information, and communicate with each other” (Ellis, Kirby and Osborne, 2023). Depending on the dominant values and beliefs of a particular society, being neurodivergent often refers to “ways in which the brain works” which sits outside or beyond “a socially constructed or defined norm” (Ellis, Kirby and Osborne, 2023).

Whilst the cognitive domains Bloom identifies provide a useful starting point, due to the hierarchal nature of the Taxonomy, there is a tendency for us to view the skills as discrete and organised sequentially in terms of complexity (Education Week, 2018). At its most powerful, the Taxonomy has shaped how we conceptualise a student’s educational journey, where students practise and master the skills at the bottom of the hierarchy in their primary education and progress up the levels, fully embracing those skills at the top of the hierarchy when moving on to further and higher education. If we think of the cognitive domains as a hierarchy, this can lead to the assumption that students who appear to struggle with skills towards the base of the hierarchy will not be able to progress to the thinking skills at the top. It is this sense of progression that needs to be reframed, particularly when considering neurodivergent learners, so that we do not do a great disservice to many of our potentially brightest students.

The following classroom scenario can help us to reframe our interpretation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Imagine a group of pupils are asked to sort and organise a messy pile of cutlery. On the face of it this may appear to be a very simple task, where learners are able to arrange or categorise the cutlery based on the most obvious organisational features. Now imagine that one student appears to be unable to complete the task. As a busy teacher, we then may assume that if the student is not able to master the seemingly simple skills of describing, organising and classifying, then they will, in turn, struggle to demonstrate the more complex skills associated with the top of the Taxonomy.

Yet, if we step back from the activity (not something the often busy and time pressed teacher has the opportunity to do!), we might start to question or rethink the hurdles which appear to be undermining the student’s ability to complete the task: The learner may ironically not be able to complete the task not because of a lack of skill, but rather because they are already thinking and working at the top of the hierarchy; when we start to think analytically, the arbitrary categories we create to make sense of the world begin to break down and become less obvious or tangible. In this example, the student may have identified multiple patterns by which the cutlery could be organised. They may observe patterns associated with size, shape, engraving, colour or the material the cutlery is made from. In other words, the student may see multiple ways of answering the question, which challenges the status quo or the assumed ‘right’ answer.

In this scenario, the student is (internally) engaging in a process of thinking which perhaps represents learning at its most exciting, challenging and creative. However, in reality, because of the progression we associate with the Taxonomy, the student’s learning may remain unseen, instead presenting to the teacher as a ‘difficult’ or ‘unwilling’ member of the group. When observing our learners and making judgements linked to their potential ability, it can be helpful to view Bloom’s Taxonomy as circle, rather than a hierarchy. This helps to not only remove the obvious stratification of the skills by level, but also encourages us to look at the fundamental relationship which exists between different types of thinking. Indeed, a young child can ‘synthesise’ in the most basic sense; they may do this frequently when they weigh up information and problem solve. In a similar way, as discussed, the simple act of remembering or classifying becomes far more challenging when the subject or topic in question becomes more complex. Therefore, Bloom’s cognitive domains provide a useful focus, but only when the complexity of the subject in question is also considered.

Furthermore, learning at its most effective relies on our ability to move between the different thinking types (whilst writing this article, I have had to engage in multiple cognitive shifts and draw on different types of cognition, often simultaneously). When we learn, we engage in an “integrated, circular, iterative” process (Education Week, 2018).

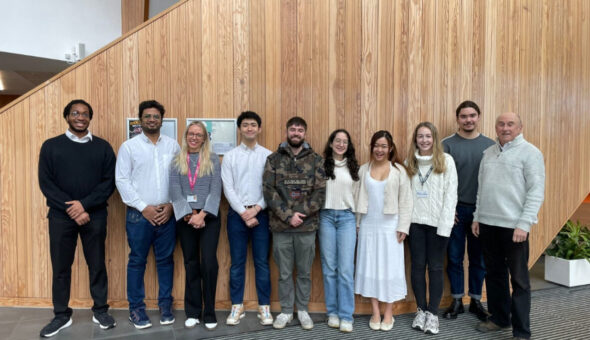

Figure 2: Bloom’s cognitive domains- an integrated, circular, iterative process

Therefore, when designing teaching and learning activities or summative and formative assessments, bear in mind the fluid rather than fixed relationship which exists between different types of skill. By considering how the domains intersect, we can better anticipate and plan to support those learners who may have heightened ability in some of the skills, whilst also finding other skills more challenging. An inclusive classroom is one where we draw on Bloom as a tool to help us question what we are observing. Indeed, when Bloom is harnessed in this way, it can remind us to challenge assumptions we might make about the student who is fearful of the blank page, of getting started or who might make lots of links verbally but perhaps struggles to do this on paper. Bloom reframed in this way can help us to better support the student who sees multiple possibilities when answering a question or indeed, limitations in the very question being framed. If a student demonstrates great potential in their thinking, they may benefit from exploring and developing learning strategies which will help them to capture, manage and organise their thinking. As teachers we may find simple low-cost and low-risk strategies enable both our neurodivergent and neurotypical students to thrive. We can embed strategies such as:

- Breaking down larger tasks into manageable steps to help students get started and also note their progress.

- Providing students with a ‘big-picture’ overview of the subject to help them to see the shape of the subject and begin to integrate new knowledge into this.

- Encouraging students to trial new ways of working and interacting with the blank page whether on paper or digitally such as tables, colour coding or formulas for writing to help students to break down the process of thinking, planning and drafting without becoming overwhelmed.

- Helping students to tailor their environment to boost their “cognitive comfort” even if this does not correlate with the accepted (often idealised) version of working in a clear, bright, quiet space, to help them harness their environment to boost their cognition (Osborne, Angus-Cole and Venables, forthcoming 2023).

Reframing our observations, interpretation and assumptions of Bloom in this way can also help busy teachers to support the wider student cohort; as many students develop their capacity to analyse, evaluate and question their subject, the tools required to organise this thinking in a way that is manageable and effective becomes increasingly important. Students may find that the strategies that they used at school no longer help them to effectively ‘manage’ the new types of thinking they are engaging in. Ironically, the more we aim for the giddy heights of Bloom’s higher order thinking skills, the more we also need effective foundational tools or skills, often associated with the base, to structure and organise this thinking. Therefore, we may find that the approaches we embed to make our teaching more inclusive for our neurodivergent learners, also provide a much-needed anchor for the wider cohort so that they can develop and demonstrate their higher order thinking skills and fulfil their potential.

The further our students progress with their educational journeys, the messier learning becomes. Certainty is replaced with nuance and to an extent doubt; this is where learning becomes exciting, creative and helps us synthesise new and original ways of thinking. As educators, we need to recognise variation in the way our students think, harness neurodiversity in our classrooms and help to ensure that our students do indeed bloom.

References

Anderson, L. W. and Krathwohl, D. R., et al (Eds..) (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Allyn & Bacon. Boston, MA (Pearson Education Group)

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. (https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/)

Education Week (2018) Here's What's Wrong with Bloom's Taxonomy: A Deeper Learning Perspective, Education Week (https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-heres-whats-wrong-with-blooms-taxonomy-a-deeper-learning-perspective/2018/03)

Ellis, P. Kirby, A. and Osborne, A. (2023) Neurodiversity and Education, Corwin

Guskey, Thomas R. (2001) Benjamin S. Bloom's Contributions to Curriculum, Instruction, and School Learning. 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Seattle, WA, April 10-14, 2001).(https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED457185.pdf)

Osborne, Angus Cole and Venables (forthcoming 2023) From Wellbeing to Welldoing: How to Think, Learn and Be Well, Corwin

Respond